We have not the myth of a son

of the sun who got burnt

by the sun and fell.

When Maponos

stole the horses of Bel

and rode skywards to the horror

of His mother He did not come to grief.

Although Maponos burned He was not burnt.

He returned instead alive and ablaze,

replenished, youth renewed,

as the Sun-Child.

So, why, black poplars, do You grieve?

Do You grieve because Your brother lives?

Do You grieve because You are jealous?

Do You grieve because You got no grief?

Or is there a story of another brother?

A forgotten son of Matrona,

daughter of the King of Annwn,

who mounted a black horse and rode

after the black sun when it set and sunk

to the depths of the Underworld?

Did He drown in a black lake?

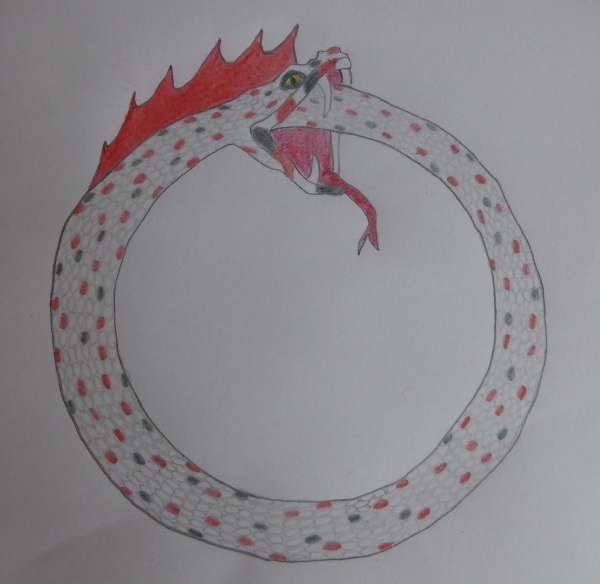

Was He eaten by a black dragon?

Or does He still wander lost in sorrow

through a labyrinth unillumined

by the rays of the black sun?

Poor brothers, did You search

for Him and almost lose yourselves?

Did You get trapped in a dark prison

and scrape Your bloody fingers

against the walls and weep?

If so, how did You get here?

Did You ride with the black sun

or with the King of Annwn on the back

of His black horse who carries lost souls?

Did He plant You here, He and His Queen,

with labyrinthine roots winding down?

Did He seal Your tears deep within?

Did He kiss Your fingers like His Bride’s,

tuck them into a yellow bud

to emerge again

only in the spring to reach

not for the black sun but the love of a mate?

Did He bring You here to tell me when

I grieve my fingers are not talons

to scrape the walls

and my tears are not sap

to entrap the insects who get in their way?

Did He bring You here so I could learn

from Your clawing, Your crying,

my clawing, my weeping,

to turn my grief inward in winter

and then, in spring, to reach out in love?

*This poem is addressed to the two black poplars who stand at the source of Fish House Brook, near to the Sanctuary of Vindos, in my hometown of Penwortham. The photograph is of one of the fallen catkins, taken in spring 2022, not quite emerged.