‘… to nobler sights

Michael from Adam’s eyes the film removed

Which that false fruit that promised clearer sight

Had bred, then purged with euphrasy and rue

The visual nerve (for he had much to see)

And from the Well of Life three drops instilled.

So deep the power of these ingredients pierced

Even to the inmost seat of mental sight

That Adam now enforced to close his eyes

Sunk down and all his spirits became entranced.

But him the gentle angel by the hand

Soon raised and his attention thus recalled:

Adam, now ope thine eyes and first behold

The effects which thy original crime hath wrought…’

Paradise Lost

I’ve recently been re-reading John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). The third or fourth time round this epic vision seems no less powerful in its depictions of Heaven and Hell and Earth both pre and post fall or radical in Milton’s writing the perspective of Satan and his inner motivations and turmoil.

As an Annuvian kind of person I will admit to feeling more sympathy with Milton’s rather magnificent Satan, refusing to serve in Heaven preferring to reign in Hell, the only one amongst the fallen angels (who include many pre-Christian gods) who dares travel to Paradise to thwart God’s plans by bringing about the fall, than the brainless Adam and Eve, Milton’s spoilsport God, or his Son.

The ending, with its deus ex machina, again was disappointing. It turns out the fall was not only predicted but designed by God to make possible and all the more powerful Jesus’ redemption of humanity. Paradise Lost is, in essence, a work of theodicy, written ‘to justify the ways of God to men’.

I’m sharing this because, whilst re-reading the book, I found the lines cited above that seem to contain Christian and pre-Christian Brythonic lore. When the archangel, Michael, purges Adam’s fallen sight he not only uses traditional plants – euphrasy, or eyebright, and rue were used for treating eye ailments – but ‘three drops’ from ‘the Well of Life’. This grants Adam visions of the future, mainly the ill-doings of his offspring until the Flood. As far as I know there is a Tree of Life but not a Well of Life in Paradise in Christian literature, which makes me wonder if it comes from another source.

The most obvious is the Welsh ‘Story of Taliesin’. In this tale Gwion Bach steals three drops of awen ‘inspiration’ from the cauldron of Ceridwen, which grant him omniscience as the all-seeing Taliesin. Milton’s evocative description of these ‘ingredients’ piercing ‘to the inmost seat of mental sight’ and putting Adam into a trance before he opens his eyes to see the future fit shares similarities with the prophetic visions of Taliesin and other awenyddion, ‘persons inspired’ referred to by Gerald of Wales.

However, although this story had been published in Welsh in the mid-16th century, it was not available in English at Milton’s time. Whether he had travelled to Wales (Milton was born in London, studied at Cambridge, lived in Berkshire, and travelled extensively throughout Europe before returning to London) or had heard the story in England in some form remains unknown.

The resemblances are so uncanny that, if he had not, it seems possible he was tapping into some deeper source. It is of interest that Milton refers not to a cauldron, but to a well, a far older image. Throughout the British and Irish myths cauldrons and wells are associated with inspiration and rebirth.

After Gwion tastes the awen Ceridwen pursues him in a shapeshifting chase and swallows him into her crochan ‘cauldron’ or ‘womb’ from which he is reborn, shining-browed, and omniscient as Taliesin. In ‘The Second Branch’ the cauldron brings dead warriors to life. In ‘The Spoils of Annwn’, refusing to ‘boil the food of a coward’ it is associated with the bardic initiation rites of Pen Annwn.

In the Irish myths the Well of Segais is associated with imbas ‘inspiration’. No-one was allowed to approach it except its keeper, Nechtan, and his three cup-bearers on pain of their eyes exploding. However, Boann, Nechtan’s wife, disobeyed. It overflowed and she was dismembered and died. The river created took her name – the Boyne. When Finn burnt his thumb whilst cooking a salmon from this river he received the imbas. In The Battle of Moytura the Tuatha Dé Dannan dig Wells of Healing and throw in their mortally wounded, who not only come out whole but more ‘fiery’ than before (!).

It seems that Milton is, indeed, tapping into a deep source. Here, in Peneverdant we once had a Well of Healing, dedicated to St Mary at the foot of Castle Hill, which I believe was associated with an earlier Brythonic mother goddess of healing waters who has revealed her name to me as Anrhuna. I believe she is the consort of Nodens (cognate with Nechtan) and the mother of Gwyn ap Nudd (cognate with Finn), Pen Annwn. Perhaps we once had a myth based around these deities that has now been lost.

In Paradise Lost, for Adam, as for many who taste the three drops of inspiration (aside perhaps for Taliesin) possessing foreknowledge is both a blessing and curse. At first he laments Michael’s gift:

‘O visions ill foreseen! Better had I

Lived ignorant of future, so had borne

My part of evil only, each day’s lot

Enough to bear! Those now that were dispensed,

The burden of many ages, on me light

At once, by my foreknowledge gaining birth

Abortive to torment me, ere their being,

With thought that they must be! Let no man seek

Henceforth to be foretold what shall befall

Him or his children…’

He is then reconciled by his perception of God’s purpose:

‘… Now I find

Mine eyes true op’ning and my heart much eased,

Erewhile perplexed with thoughts what would become

Of me and all mankind, but now I see

His Day in whom all nations shall be blest.’

‘O goodness infinite, goodness immense!

That all this good of evil shall produce

And evil turn to good more wonderful

Than that which by Creation first brought forth

Light out of darkness!’

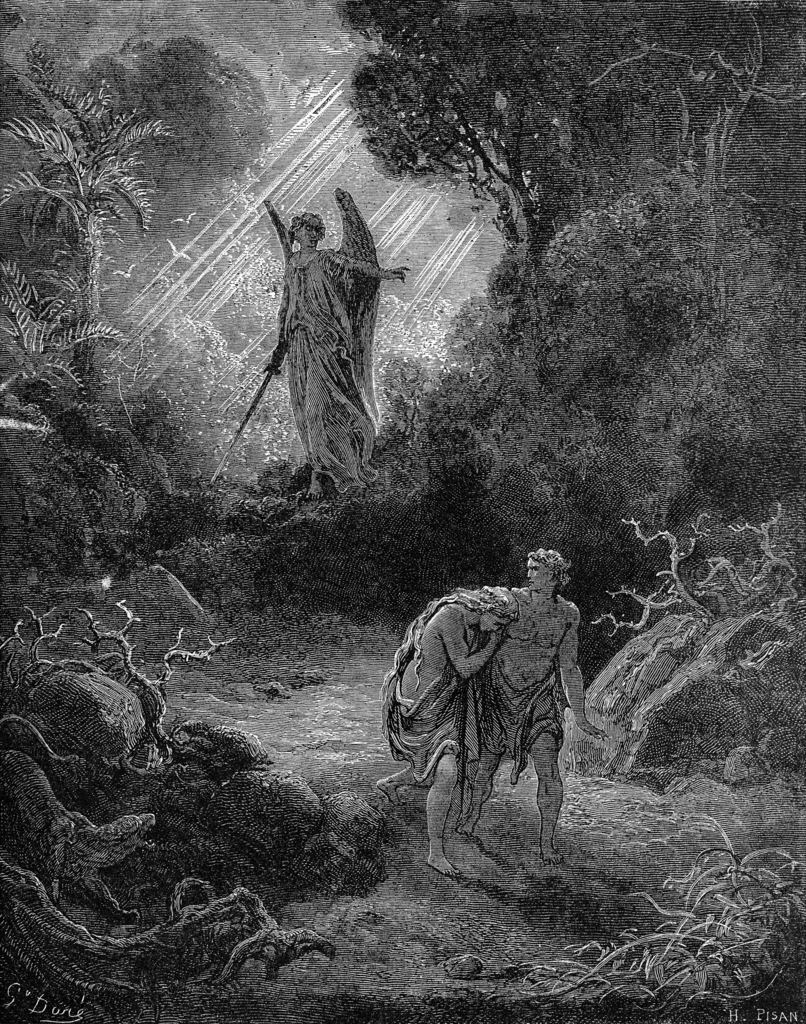

Adam’s visions give him the strength to depart with Eve from Paradise to Earth to beget humankind. The gate to Paradise, to the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge, and no doubt to the Well of Life is barred and guarded by a ‘flaming brand’ ‘the brandished Sword of God’ ‘fierce as a comet’.

In Christian literature, in contrast to the simplistic notion preached to school children that the souls of good people go to Heaven and those of bad people go to Hell, Paradise is not truly regained until after the Apocalypse and Jesus’ harrowing of Hell and the resurrection of the dead.

It may be suggested that, in our Brythonic myths, all souls return to the Well of Life. That, with a little awen to awaken ‘mental sight’, the living can travel in spirit to Annwn and be reborn as awenyddion.

Here, in Peneverdant, where the well has run dry due to the foolishness of humans shattering the aquifer when moving the river Ribble to create Riversway Dockland, it remains possible to traverse the waters of the past, of the Otherworld, to return to the unfathomable source from which Milton drew.