‘At the head of the line…

the spoil was the cow of An(r)hun(a).’

~ The Battle of the Trees

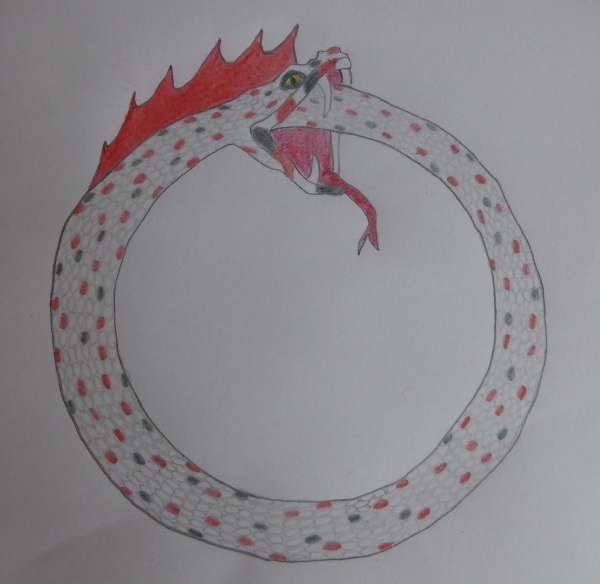

I am the Cosmic Cow.

I am white and red with seven legs,

eleven udders pouring the whitest milk,

a red crown of twelve stars upon my head.

My cow bells sound through the sea of stars.

My milk is the origin of the Milky Way.

I am ever loving and ever giving.

You cannot capture me because

I always come willingly.

You cannot take my milk

because I am always pleased to give.

Milk me until your fingers are bare bone

and my milk will never run dry,

not until you have used

every bucket in the world

and you have emptied every mine.

I am ever living and ever giving.

I can melt the heart

of the cruelest warlord

with one look from my soft eyes

And halt the wars betwen nations

with the scent of cud between my soft lips.

I am the spoil but I cannot be spoilt –

white, blessed, holy am I.

‘The Battle of the Trees’, in The Book of Taliesin, records a conflict between the Children of Don and Arawn, King of Annwn, and His otherworldly monsters.*

We are told ‘At the head of the line / the spoil was the cow of Anhun’. The cow, as the spoil, is absolutely central to the battle but, unfortunately we find out nothing else about her. All we are told is, ‘It caused us no disaster’. This suggests the cow is a benevolent being but we find out nothing more.

Marged Haycock suggests that Anhun is St Anthony and this buch ‘cow’, ‘buck’, ‘buck-goat’ or ‘roebuck’ might be the satyr he met in the wilderness.

This didn’t feel quite right to me – I couldn’t see the Children of Don fighting over a satyr. For a long while I saw this animal as an Annuvian cow akin to the Brindled Ox, who was stolen in ‘The Spoils of Annwn, but could discern no more.

Then, a few months ago, I was sitting looking at the name ‘Anhun’ and saw a couple of spaces between the letters filled in by the name An(r)hun(a). This title means ‘Very Great’ and she is a found Goddess who myself and a number of other awenyddion have come to know as the Mother of Annwn and of its ruler, Gwyn. (It’s my personal belief Gwyn and Arawn are titles of the same God).

Anrhuna’s association and possible identification with a magical cow ties in with parallels from Irish mythology. Her Irish cognate is Boann or Bó Find, which might derive from the Proto-Celtic *Bou-vindā ‘White Cow’. She is the wife of Necthan (Nuada) who is cognate with Nodens / Nudd ‘Mist’ the father of Vindos / Gwyn ‘White’. *Bou-vindā fits with Her being the mother of Vindos.

Bo Find ‘White Cow’ and Her sisters Bo Rhuad ‘Red Cow’ and Bo Dhu ‘Black Cow’ came from the Western Sea to make barren Ireland green and fertile.

My personal gnosis around the Cow of Anrhuna presents her as a cosmic cow akin to Auðumbla ‘hornless cow rich in milk’ whose milk fed the primordial giant, Ymir, from whom the world was made in the Norse myths. Also to the sacred cow and bovine appearances of the Divine Mother, Kamadhenu, and the Earth Mother, Prithvi, in the Hindu religion.

Her loving and giving nature and endless supply of milk also link to later folklore. In the Welsh lore we find Gwartheg y Llyn, ‘Cows of the Lake’ who belong to the lake-dwelling Gwragedd Annwn ‘Wives of the Otherworld’. They are usually white or speckled / brindled and are captured for their milk and, on being mistreated or milked dry, disappear back to their lakes.

In England we find the legend of the Dun Cow who provides plentiful milk until a witch tricks her by milking her with a sieve not a pail and she dies of shock. There are two variants here in Lancashire. In one the dead cow’s rib is displayed at Dun Cow Rib Farm in Longridge. In a happier variant her milk saved the people from the plague and she was buried at Cow Hill in Grimsargh.

I now like to think these stories derive from a deeper myth featuring the Cow of Anrhuna. It also made me smile that the cattle of Annwn, likely the cow’s daughers, are associated with the Wives of Annwn after my marriage to Gwyn.

*Gwydion fashions the trees ‘by means of language and materials of the earth’. Lleu is the battle-leader, ‘Radiant his name, strong his hand, / brilliantly did he direct a host’. Peniarth MS 98B records how the battle was caused by Amaethon stealing a roebuck, a greyhound and a lapwing from Arawn. Arawn’s monsters include a black-forked toad, a beast with a hundred heads and a speckled crested snake.