29 miles east along Hadrian’s Wall from Carlisle lies the ruins of the Roman village of Vindolanda. I was drawn there because the name Vindolanda, usually translated ‘White Fields’ or ‘White Lands’, derives from *Windo ‘fair, white, blessed’ and this is the root of Gwyn ap Nudd’s name. Gwyn may have been known as Vindos in Iron Age Britian. There are no known dedications to Vindos but it seems possible he was venerated at Vindolanda and Vindogladia.

Evidence for the place-name Vindolanda comes from the Vindolanda Altar, which was found at the edge of the settlement. It reads, ‘Pro domu divina et Numinibus Augustorum Volcano sacrum vicani Vindolandesses curam agente…V S L…’ ‘For the Divine House and the Deities of the Emperors, the villagers of Vindolanda (set up) this sacred offering to Volcanus, willingly and deservedly fulfilling their vow, under the charge of…’

Here we find the name Vindolandesses ‘villagers of Vindolanda’. The altar was set up for Volcanus, Roman god of volcanoes and blacksmithing. As there isn’t any evidence of volcanic activity in the area, I assume the villagers chose Volcanus because iron smelting and forging took place at Vindolanda.

Surprisingly there is no information on display about what was there before the Roman invasion. When I asked a member of staff, she said it was farmland and told me the name Vindolanda derives from the land being coloured white by natural springs running from above the village and Barcombe Hill.

Near the wells and water tanks above the ruins is a notice which mentions ‘many springs and good steams’ and states ‘the most powerful source lay near here’. The stone aqueduct which carried the water into the village is still visible, but its source appears to have run dry.

Adjacent to the wells and tanks stands the remains of a Romano-Celtic temple ‘used by soldiers to celebrate both local and Roman gods’. No individual deities are named. Gwyn is associated with the White Spring beneath Glastonbury Tor and I’ve experienced his presence at Whitewell here in Lancashire.

It’s my intuition he could have been worshipped as Vindos in this temple beside the source of the white springs. My excitement at potentially discovering one of Vindos/Gwyn’s most ancient sacred sites was tempered with sadness that the springs had run dry.

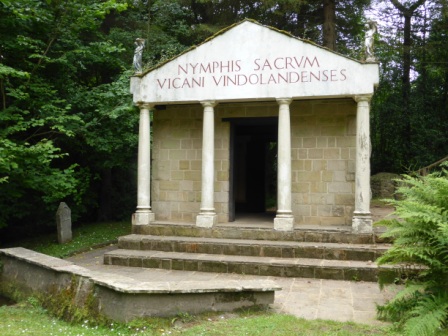

Below the village near to Chainley Burn is a reconstructed shrine with the painted inscription, ‘NYMPHIS SACRUM VICANI VINDOLANDENSES’ ‘The villagers of Vindolanda (dedicated this temple) sacred to the Nymphs’. This is based on an ornate temple still standing in the 18th century. There is plenty of evidence Vindolanda was a place of water worship.

*

Nine forts have existed at Vindolanda, built between 85AD and 370AD. Archaeological evidence suggests it was occupied long into the Dark Ages. It has been the home of soldiers from many different cultures; the 9th cohort of Batavians (Netherlands), the 1st cohort of Tungrians (Belgium), the 4th cohort of Gauls (France), the 2nd cohort of Nervians (Belgium) and Vardullian Cavalry (Spain). These men were removed from their homelands and stationed across the Empire. Defeated Britons were sent to fight for Rome in other countries.

Rows of houses, storehouses, a tavern and mausoleums lie outside the walls of the fort which, when they were built in 211AD, were two storeys high with impressive guard towers (much of the stone has since been stolen). Inside are more houses and stores, bathhouses, workshops, horrea ‘granaries’, the principia ‘headquarters’ (where regimental officers and clerks maintained records) and the praetorium ‘house of the commanding officer’.

One of the buildings was a temple to Jupiter Dolichenus, an ancient weather god from the south-east of modern Turkey, who is depicted holding bolts of lightning whilst standing on a goat. His temple was destroyed then set on fire in 370AD when paganism was replaced with Christianity and a Christian church built within the fort. This is significant as it provides an exact date for the conversion of the people of Vindolanda to Christianity. It seems likely other Roman-ruled populaces on Hadrian’s Wall were converted around the same time.

Within the museum are a large variety of finds perfectly preserved by the peaty soil. 6,000 shoes (but only one pair!) of all shapes and sizes were found in the ditches surrounding the fort, along with armour, weaponry, tents, a drawstring bag, cavalry standard and equipment for horses.

I was particularly impressed by the chamfron; a horse’s ceremonial face-mask made from leather with bronze fittings and protection for the eyes. Gwyn speaks of Carngrwn as a ‘white horse gold-adorned’. I could imagine Carngrwn wearing similar headgear. Could his depiction in The Black Book of Carmarthen have originated from the Land of White Springs and its tradition of elaborately decorated saddlery?

*

Most famous of all are the Vindolanda tablets. These inscriptions on wood date back to 121AD and provide some fascinating insights into the lives and viewpoints of the soldiers of Vindolanda.

‘…the Britons are unprotected by armour. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords, nor do the wretched Britons (Brittonculi) mount in order to throw their javelins.’

‘…order (accommodation) to be given to…, but also a lodging where horses are well (looked after). Farewell, brother dearest to me’

‘Tomorrow nice and early in the morning come to Vindolanda, so that (you can join the counting of the census)’

Pieces of writing not on display are summarised on the surrounding walls:

Tranquilius ‘Who supplied some undergarments to the Cerialis household’

Claudius Super ‘A centurion, apologising to Cerialis for failing to attend Sulpicia Lepidina’s birthday celebrations’

Flavius Genialis ‘A predecessor prefect to Cerialis, who appears to have had a nervous breakdown at some point’

Lucius ‘A cavalry troop commander (decurion), receives a letter from a friend reporting on a gift of 50 oysters from a place called Cordonovi’

Virrilus ‘A veterinary surgeon (veterinarius), who is reminded by Chrauttius that he hasn’t yet sent the castrating shears that he promised’

There is a small collection of statues and altars of gods and goddesses. These include statues of Priapus, Maponus and statuettes of Venus and Dea Nutrices and altars to the Veteres and an unknown god which frustratingly simply reads ‘Deo’.

They represent only a small portion of the dedications found at Vindolanda. I hoped to find an altar to Mogons ‘great one’ inscribed ‘Mogonti et Genio Loci’, as Vindos may have been viewed as the genius of the place. However, it was not on display.

That’s only a small complaint. The people who work at Vindolanda have done a superb job in their excavations of the Roman forts and preservation of the objects and remains of the people who lived there. No inscriptions to Vindos have been found, but their work is ongoing and no-one knows what might be recovered next…

*

Vindos god of the Land of White Springs

where the springs flow no longer

yet memories flow from

Annwn’s wells

soldiers from a thousand distant lands

have whispered your name

water holds their peaty memories

I do not wield a stylus on birch

nor chisel on altar

to engrave your greatness here forever

I let my words fall on the wind

spiralling downward

to join

the well-springs