In the land where I live, spring awakes. Snowdrops in their prime unfold the voluminous skirts of their lanterns. Lords and ladies push their courtship through the soil alongside first signs and scents of ransoms. Swollen mosses take on a bright green living vibrancy.

In the land where I live, spring awakes. Snowdrops in their prime unfold the voluminous skirts of their lanterns. Lords and ladies push their courtship through the soil alongside first signs and scents of ransoms. Swollen mosses take on a bright green living vibrancy.

As I walk the path centuries of ancestors walked to St Mary’s Well, I hear the loudness of a thrush. Could it be the one who calls me from sleep each morning, speckled chest blanched and white as birch amongst ash and sycamore? The trees hold back for now, but I know the sap will start rising soon.

I pass the site of the healing well and cross the road to the War Memorial. Splashes of pink, purple and yellow primroses are planted in beds before the Celtic cross. Etched on blue-grey slabs are the names of seventy-three men who lost their lives in the First World War and forty-six who died in the second. They are honoured and remembered here. I also think of the dead who have no memorial or whose memories have been erased or forgotten.

I follow the footpath uphill onto Church Avenue. Leading to St Mary’s Church, it once went to a Benedictine Priory, dissolved and more recently demolished. A strange road this; trodden by pilgrims in search of miraculous cures and by funeral processions. By soldiers too, maybe armies, defending this crucial position from what we now see as the castle motte.

Passing the church on the hill’s summit I stand in the graveyard amongst tilted and fallen headstones, beneath sentinel beech trees whose shells and bronzed and curling leaves still litter the greening earth.

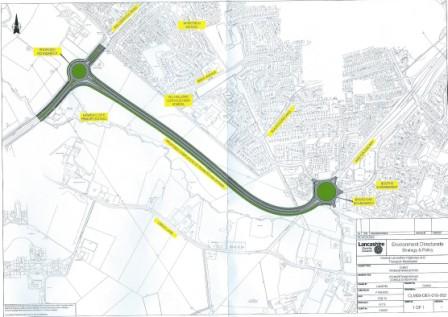

There’s no access to the motte’s vantage point, but through leafless trees I can make out the city of Preston with its clock tower, steeples, tower blocks and huge manufacturies along Strand Road. I recall images of its panoply of smoking chimneys, flaming windows, imagine the pounding Dickensian melancholy-mad elephants.

Preston’s sleeker now. Cleaner. Less red and black. Concrete grey. Not so smoky. But sometimes the industrial pall still holds. Somewhere behind its walls lies a medieval town and behind that…

The Pennines form a sweeping backdrop, rising higher than Priest Town’s spires ever could; Parlick, Wolf Fell, Longridge Fell, Billinge Hill, Great Hill, Winter Hill. An easterly green and purple barricade. To the west, the river Ribble, Belisama, strapped into her new course, stretches long arms to her shining estuary. A sea gull cries over the horizon and disappears.

I’ve spent several years researching the history of Penwortham. The Riversway Dockfinds mark the existence of a Bronze Age Lake Village. Ballista balls on Castle Hill and a huge industrial site at Walton-le-dale ascertain a Roman presence. Following the breakdown of Roman rule, history grinds to a halt.

There is a black hole in Penwortham’s past the size of the Dark Ages; during the time of the Old North.

Historians have conjectured about this. David Hunt and Alan Crosby agree that place names (where we find a mixture of Brythonic and Old English, like Penwortham* often conjoined) suggest a gradual settlement of the local area by Anglo-Saxons during the seventh century. They say Penwortham’s remoteness on the edges of Northumbria and Mercia meant it was not a major concern. However, this conflicts with the significance of its location as a defensive position for the early Britons and Romans and later probably for the Saxons of Mercia and the key role it played for the Normans during the harrying of the North.

History starts up again with the Saxon hundreds, invasions from Scandinavia and the Norman Conquest. But what happened in between?

Unfortunately, likewise, there is a black hole in the history of the Old North the size of Penwortham. And it isn’t the only one.

The very concept of ‘Yr Hen Ogledd’ ‘the Old North’ is problematic. It is a term used post datum by scholars to identify an area of land covering the majority of northern England and southern Scotland from the time of the breakdown of Roman rule in the fifth century until the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria came to dominate in the eighth century.

During this period, it was simply known as ‘Y Gogledd’ ‘the North’. Its people spoke a Brythonic language known as Cumbric, which was similar to the Cymric language of the Welsh. Its rulers ‘Gwŷr y Gogledd’ ‘the Men of the North’ claimed common descent from either Coel Hen (Old King Coel) or Dyfnawl Hen. Again, the genealogies are problematic because they were created by kings to certify their reign by tracing their lineage back to legendary ancestral figures.

The main kingdoms of the Old North are usually identified as Alt Clud, in the south-west of Scotland, which centred on Dumbarton and later became Strathclyde; Gododdin, in the south-east of Scotland, which had a base at Edinburgh; Elmet, in western Yorkshire and Rheged in north-west England.

The location of Rheged is a matter of ongoing debate. For Ifor Williams it centres on Carlisle and the Eden Valley and covers Cumbria, the Solway Firth and Dumfries and Galloway. John Morris posits the existence of a northern Rheged in Cumbria and a southern Rheged that extended into Lancashire and Cheshire. On the basis of landscape and resources, Mike McCarthy suggests a smaller kingdom or set of sub-kingdoms existed either north or south of the Solway. If McCarthy is correct, we do not have a name for present day Lancashire at all but a black hole the size of a county or larger!

Another problem is that textual sources about the Old North are extremely limited. We have some historical records such as the Annales Cambriae, the Historia Brittonum and Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Much of the history of this period is derived from the heroic poetry of the Dark Age bards Taliesin and Aneirin. Later saga poetry construes dramatic dialogues between characters associated with earlier events.

Research leads to where history and myth converge but can take us no further. It becomes necessary to step beyond study across the threshold to otherworlds where the past, our ancestors and deities still live.

So I speak my intentions to the spirits of place; the Lady in the Ivy with her glance of green, wood pigeons gathered in the trees, the people buried here in marked and unmarked graves.

I speak with my god, Gwyn ap Nudd, who abides beyond this land but sometimes seems closer than the land itself. The god who initiated and guides this quest.

His suggestion: what is a black hole but a portal?

Our agreement stirs a ghost wind from behind the graves, rustling bronze beech leaves and tree whispers from above.

The hill seems greener. A single white sea gull barks. Then long-tailed tits come chittering and twirling to the brambles.

*Penwortham first appears in the Domesday Book in 1086 as ‘Peneverdant.’ Writing in 1857 Rev. W. Thornber claims this name is of British origin and ‘formed of three words- pen, werd or werid and want, as Caer werid, the green city (Lancaster) and Derwent, the water, that is the green hill on the water’. This describes exactly how I imagine Castle Hill would have looked during the eleventh century near the Ribble on the marsh. However, ‘verdant’ has always sounded more like French for ‘green’ to me.

*Penwortham first appears in the Domesday Book in 1086 as ‘Peneverdant.’ Writing in 1857 Rev. W. Thornber claims this name is of British origin and ‘formed of three words- pen, werd or werid and want, as Caer werid, the green city (Lancaster) and Derwent, the water, that is the green hill on the water’. This describes exactly how I imagine Castle Hill would have looked during the eleventh century near the Ribble on the marsh. However, ‘verdant’ has always sounded more like French for ‘green’ to me.

Alan Crosby says ‘Peneverdant’ results from a Norman scribe trying to write an unfamiliar word (which was likely to have been in use for up to 500 years) phonetically. He tells us the ‘Pen’ element in Penwortham is British and means ‘prominent headland’ whilst ‘wortham’ is Old English and means ‘settlement on the bend in the river’.

If Penwortham had an older British name prior to Saxon settlement, it is unknown. I can’t help wondering if it would have been something like ‘y pen gwyrdd ar y dŵr,’ which is modern Welsh for ‘the green hill on the water’. It’s not that far from Peneverdant.