Beside the source of the brook in Greencroft Valley stand two black poplars. There aren’t any known British myths about black poplars but, in Greek myth, they are associated with Hades (the Underworld) and death.

In Homer’s Odyssey, poplars, described in different translations as ‘tall’ and ‘dusky’, so likely black, with willow, form Persephone’s Grove. Springs, throughout world myth, are seen as entrances to the Underworld.

In another story from ancient Greece, Phaethon, son of the sun God, Helios, drives his father’s chariot too close to the sun. His blazing end brings deep grief to his sisters, who are transformed into black poplar trees. The amber sap is said to be their tears. Thus its associations with death and sorrow.

In more recent folklore the red male catkins are referred to as ‘Devil’s Fingers.’

This leads me to believe that there might have once been parallel British myths about black poplar, connecting it with springs at the entrance to Annwn and with the groves of Annwn’s Queen. Perhaps there was once a story in which the red male catkins were the bloody fingers of Annwn’s King?

I will admit that I’m not sure if these trees are true black poplars (Populus nigra) or hybrids because black poplars are rare. Plus, I’m not referring to the true source of Fish House Brook but to the outflow pipe that the culverted brook emerges from. The original source would have lain further south, somewhere on Penwortham Moss, which has been drained and replaced by housing. The brook is culverted under the gardens on the other side of my street, Bank Parade, also giving its name to Burnside Way. I feel this relates to my founding of the Sanctuary of Vindos / Gwyn ap Nudd, a King of Annwn, very near to the ‘black poplars’ at the ‘source’.

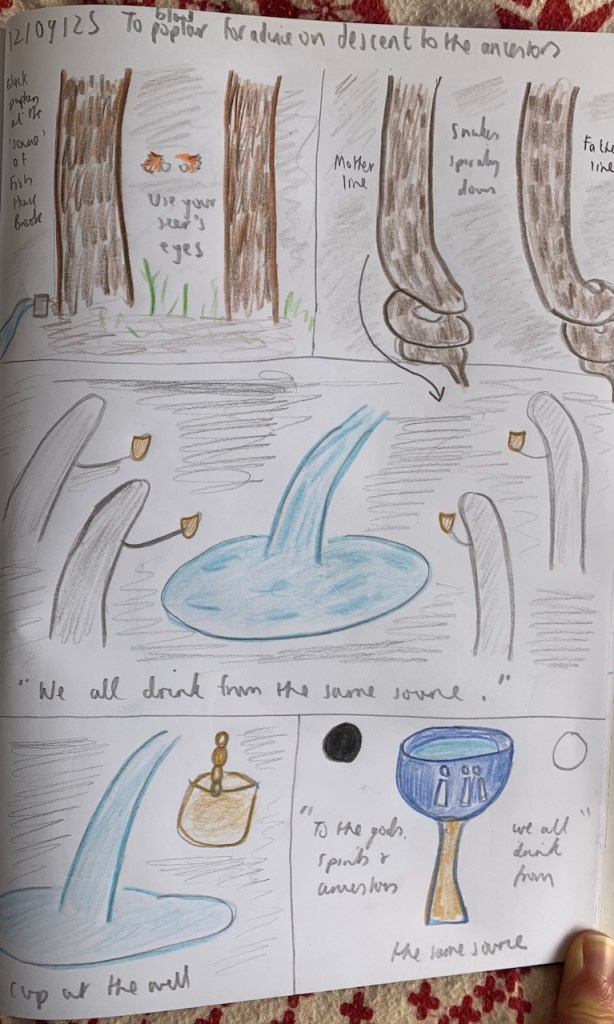

In a shamanic journey I visited the poplars for advice on descending to the ancestors in preparation for some ancestral healing work. I was shown the left tree represented my mother line and the right my father line. I slid down the roots of the left into a cavern where a group of spirits were drinking from cups from the same source. I was told that on the new and full moons I must consecrate a cup of water and make an offering:

“To the Gods,

spirits and ancestors –

we all drink from the same source.”

I felt this related to keeping the source clean – something I have been trying to do as a volunteer in Greencroft Valley with the Friends group I set up (now part of Guardians of Nature).