Introduction

Over the past few years, since my late diagnosis of autism in 2021, I have been researching its affects on the brain, body and nervous system in order to gain a deeper understanding of the ways being autistic has impacted my life.

Looking back it has brought many benefits such as being incredibly focused on my special interests, creativity, intuition and the ability to think outside the box. However it has also has its costs. My struggles with sensory and information overload have made it impossible to hold a regular job and being unable to handle publicity played a role in my failing to make a living from my writing.

This led me to seeing myself as a failure and not understanding why. My autism diagnosis coupled with more recent learnings has revealed the reasons I find everyday life overwhelming and helped me develop better coping strategies. I’m sharing my insights here in the hope they will help others.

What is autism?

The term ‘autism’ was coined by psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911. It is composed of the Greek autós ‘self’ and ism ‘a doctrine or theory’ and was used ‘to describe a schizophrenic patient who had withdrawn into his own world.’ (1)

It was first used as a diagnostic category in 1943 in a paper by a physician called Leo Kanner in a paper titled ‘Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact.’ Here he speaks of eleven children with shared symptoms – ‘the need for solitude; the need for sameness. To be alone in a world that never varied.’ (2)

The Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders 5 uses two criteria to diagnose autism – ‘Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction’ and ‘restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.’ (3)

Part One: The Causes of Overload

Autism and Neurodevelopmental Differences in the Brain

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disability that has its basis in differences in the brain that began developing in utero. In The Autistic Brain autistic authorTemple Grandin speaks of some of the ‘anomalous growth patterns’ that she has discovered in her brain through neuro-imaging and how these relate to her life experiences. She tells us that her ‘cerebellum is 20 percent smaller than the norm’ explaining her lack of balace and motor coordination. (4) Her left ventricle is 57 per cent longer than her right extending into her parietal cortex – a disturbance which she associates with her poor working memory and lack of maths skills. Having more connections between her inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) explains her excellent visual memory.

Most interestingly for me she notes: ‘My amygdalae are larger than normal. The mean size of the three control subjects’ amygdalae was 1,498 cubic millimeters. My left amygdala is 1,719 cubic millimeters, and my right is larger still — 1,829 cubic millimeters, or 22 percent greater than the norm. And since the amygdala is important for processing fear and other emotions, this large size might explain my lifelong anxiety… Enlarged amygdalae are also often seen in people with autism. Because the amygdala houses so many emotional functions, an autistic can feel as if he or she is one big exposed nerve.’ (5)

I found this incredibly relatable as my sensory sensitivities and emotional responses to them have often made me feel like ‘one big exposed nerve’ too. Likewise my fear of being overwhelmed by sensations and emotions and having shutdowns and meltdowns has resulted in struggles with anxiety. These insights inspired me to learn more about the amygdala and its function.

The Amygdala and Emotional Responses

An excellent description of how sensory experience is processed and delivered to the amygdala and how this brings about an emotional response is provided by Bessel van der Kolk in The Body Keeps the Score.

‘Sensory informationabout the outside world arrives through our eyes, nose, ears, and skin. These sensations converge in the thalamus, an area inside the limbic system that acts as the “cook” within the brain. The thalamus stirs all the input from our perceptions into a fully blended autobiographical soup, an integrated, coherent experience… The sensations are then passed on in two directions—down to the amygdala, two small almond-shaped structures that lie deeper in the limbic, unconscious brain, and up to the frontal lobes, where they reach our conscious awareness… The central function of the amygdala, which I call the brain’s smoke detector, is to identify whether incoming input is relevant for our survival… If the amygdala senses a threat… it sends an instant message down to the hypothalamus and the brain stem, recruiting the stress-hormone system and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) to orchestrate a whole-body response. Because the amygdala processes the information it receives from the thalamus faster than the frontal lobes do, it decides whether incoming information is a threat to our survival even before we are consciously aware of the danger. By the time we realize what is happening, our body may already be on the move.’ (6)

Van der Kolk not only describes brilliantly how the amygdala brings about our emotional responses but explains why we respond to situations which are threatening or overwhelming with extreme reactions such as outbursts of anger, panic attacks and in the case of autistic people meltdowns and shutdowns before the conscious mind comes on board.

Intense World Syndrome

Van der Kolk links his insights into the amygdala to responses to trauma and in particular to PTSD. These connections also seem valid for autistic people for whom living in a world of sensory and information overload can be traumatic.

This is described in the ‘Intense World’ paper, published in 2007, as ‘intense world syndrome’. The authors say ‘excessive neuronal processing may render the world painfully intense’ resulting in autistics retreating ‘into a small repertoire of secure behavioral routines that are obsessively repeated.’ ‘Impaired social interactions and withdrawal may not be the result of a lack of compassion, incapability to put oneself into someone else’s position or lack of emotionality, but quite to the contrary a result of an intensely if not painfully aversively perceived environment.’ (7) For an autistic person sensory overload is traumatic and leads to them withdrawing from the world.

Sensory Gating Deficits

Another factor relating to overload in autistic people is differences in sensory gating. In Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm Stephen Buhner describes ‘sensory gating channels… as tiny apertures or gates or doors in specific sections of the nervous system’s neural network… like a series of locks on the river of incoming sensory flows.’ (8) He speaks of how, as we grow up, these channels, for most people, narrow and close. Those with ‘gating deficits’ (such as autistics) remain open and they are more likely to suffer from sensory overload which can lead to ‘a breakdown in cognitive integrity.’ (9)

Part Two: Coping with Overload

Self-Awareness and Befriending Inner Experience

In The Body Keeps the Score van der Kolk describes methods of coping with trauma that can also be harnessed by autistics to help cope with extreme emotional responses to sensory overload. Fundamental is restoring the balance between the rational and emotional brains, the pre-frontal cortex ‘the watch tower’ and the amygdala ‘the smoke detector’ or ‘alarm system.’

He says: ‘the only way we can consciously access the emotional brain is through self-awareness, i.e. by activating the medial prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that notices what is going on inside us and thus allows us to feel what we’re feeling… and learning to befriend what is going inside ourselves.’ (10)

He tells us that ‘those who cannot comfortably notice what is going on inside become vulnerable to respond to any sensory shift either by shutting down or by going into a panic—they develop a fear of fear itself… The price for ignoring or distorting the body’s messages is being unable to detect what is truly dangerous or harmful for you and, just as bad, what is safe or nourishing. Self-regulation depends on having a friendly relationship with your body. Without it you have to rely on external regulation—from medication, drugs like alcohol, constant reassurance…’ (11)

Van der Kolk here describes my personal experiences perfectly. For most of my life I’ve been alienated from my body and the confusion of sensations and emotions that it throws at me and I’ve always felt out of control. Due to not being self-aware I have struggled in social situations with family, friends and work colleagues due to not being able to read people or control my reactions. I’ve been subject to outbursts of anger and panic attacks and depended on alcohol to tolerate socialising and to down-regulate afterwards.

Becoming more self-aware and befriending my inner experiences has led to a more conscious and caring attitude towards my body and to feeling more in control.

Movement and Meditation as Medicine

Van der Kolk tell us: ‘If you want to manage your emotions better, your brain gives you two options: You can learn to regulate them from the top down or from the bottom up… Top-down regulation involves strengthening the capacity of the watchtower to monitor your body’s sensations. Mindfulness meditation and yoga can help with this. Bottom-up regulation involves recalibrating the autonomic nervous system. We can access the ANS through breath, movement, or touch.’ (12)

He says: ‘In contrast to the Western reliance on drugs and verbal therapies, other traditions from around the world rely on mindfulness, movement, rhythms, and action. Yoga in India, tai chi and qigong in China, and rhythmical drumming throughout Africa are just a few examples. The cultures of Japan and the Korean peninsula have spawned martial arts, which focus on the cultivation of purposeful movement and being centered in the present… These techniques all involve physical movement, breathing, and meditation.’ (13)

Van Der Kolk’s words really resonated with me because I have have been led my a combination of guidance and intuition to these practices. When I was diagnosed with anxiety in 2004 I was put on Venlafaxine and advised to take up exercise. I started going to the gym and learning a martial art – Taekwondo. Both forms of movement have helped me to regulate my stress levels.

Since then physical exercise has been a massive help in self-regulating. I’ve been through periods of long-distance walking and running, practicing martial arts, cycling and my current passion is strength training.

Meditation is something I’ve found much harder. As someone who is incredibly imaginative and has a busy mind I’ve always been good at visualisation meditations but meditation in the more traditional sense of focusing on one thing or simply witnessing thoughts has been more difficult.

I dismissed these practices as ‘Eastern’ and ‘not for the Western mind’ until I started practicing yoga in 2023 as a result of a sports injury and advice from my PT. One of my teachers, Bre, of Breathe and Flow, said if we find something difficult it’s often the thing we need most. So it was with yogic meditation.

As I have persevered I have found that focused meditation helps slow down my thoughts and calm my mind and training my witness helps prevent me from become so caught up in overwhelming sensations and emotions.

Disovering that by changing our breathing patterns through breathwork I can also change my emotions and my thoughts has been a life-changer.

Rhythmic drumming has also been helpful. As someone who has been practicing shamanism for many years being able to use various drumbeats such as the journeybeat to shift into trance and a slow heartbeat to calm my nervous system have helped me to cope with being overwhelmed.

Moving Up and Down the Polyvagal Ladder

Another discovery that has changed my life is learning about polyvagal theory. I first came across this on a Radical Embodiment course with my supervisor Jayne Johnson and Alex Walker. Introduced by Stephen Porges in 2004 it posits three states of the nervous system – social engagement (ventral vagal), flight or fight (sympathetic) and freeze (dorsal vagal).

Coming to understand and be aware of these states has aided me to become able to move through them. When I feel anxiety and a shift towards flight or fight checking in with my nervous system to see what it needs to feel safe. When I feel myself getting burnt out and moving towards shutdown / freeze cutting down on social activities and taking time alone to rejuvenate.

Mastering the Gates

Buhnen mentions that having open sensory gating is not always a bad thing. In face ‘gating remains very open, especially among young children, artists, schizophrenics and specialists of the sacred such as shamans and Buddhist masters, and those ingesting psychotropics.’ (14) ‘In cultures that recognize the importance of this capacity, this group of people are trained to use their enhanced perceptual capacities for the benefit of the group.’ (15)

He speaks of how we can intentionally shift gating by ‘1) having a task that demands a greater focus on incoming sensory data flows, or 2) regenerating a state similar to that which occurred during the first few years of life, or 3) by altering the nature of the gating channels themselves by shifting consciousness.’ (16)

Focusing on a single task, whether it’s writing a poem or article, gardening, or lifting weights, has always been a great way of staying present and not getting overwhelmed by troubling sensations and emotions. Over the years training in both shamanism and meditation has enabled me to get better at recognising and shifting between states of consciousness.

A yogic practice that I began learning in August last year on a course in meditation with the Mandala Yoga Ashram has been particularly helpful. This is Antar Mouna ‘Inner Silence’. In the first stage you focus on sensations – sound, touch, inner sight, taste and smell. You practice focusing on, for example, louder sounds, softer sounds, all the sounds, then shifting to touch, then all the sensations at once so you’re in a sea of sensations. Fundamental is not attaching any place or meaning to the sensations but simply experiencing them as they arise in themselves. I believe this to be a form of mastering sensory gating. It has been very useful in helping me to shift my attention away from and be less bothered by noise from my neighbours.

Slowing the World Down

So far I’ve mentioned things autistic people can do to cope with overload. It would also be of benefit if the world was a less overwhelming place. Grandin cites autistic author Donna Williams: ‘the constant change of most things never seemed to give me any chance to prepare myself for them… Stop the world, I want to get off… stop the world, at least slow it down… The stress of trying to catch up and keep up… often became too much and I found myself trying to slow everything down and take some time out.’ (17)

Like Williams I’ve also found it difficult to keep up, in the workplace, in the blogosphere, on social media with quicker and quicker platforms appearing. As the world is not slowing down I’ve been left with no choice but to get off. I’ve abandoned hope of regular work, left social media, and cut down from reading around 50 different blogs and websites to a small select few.

Monasticism – Embracing Withdrawal

When Bleuler defined autism he depicted withdrawal into oneself as a disorder. Withdrawal is often associated with mental health issues and withdrawn persons are invariably encouraged to ‘come out of themselves’.

In contrast to this, within monastic traditions, withdrawal from the world is advocated as a positive movement and a necessary condition of attaining greater self-knowledge and knowledge of the Gods and of the universe.

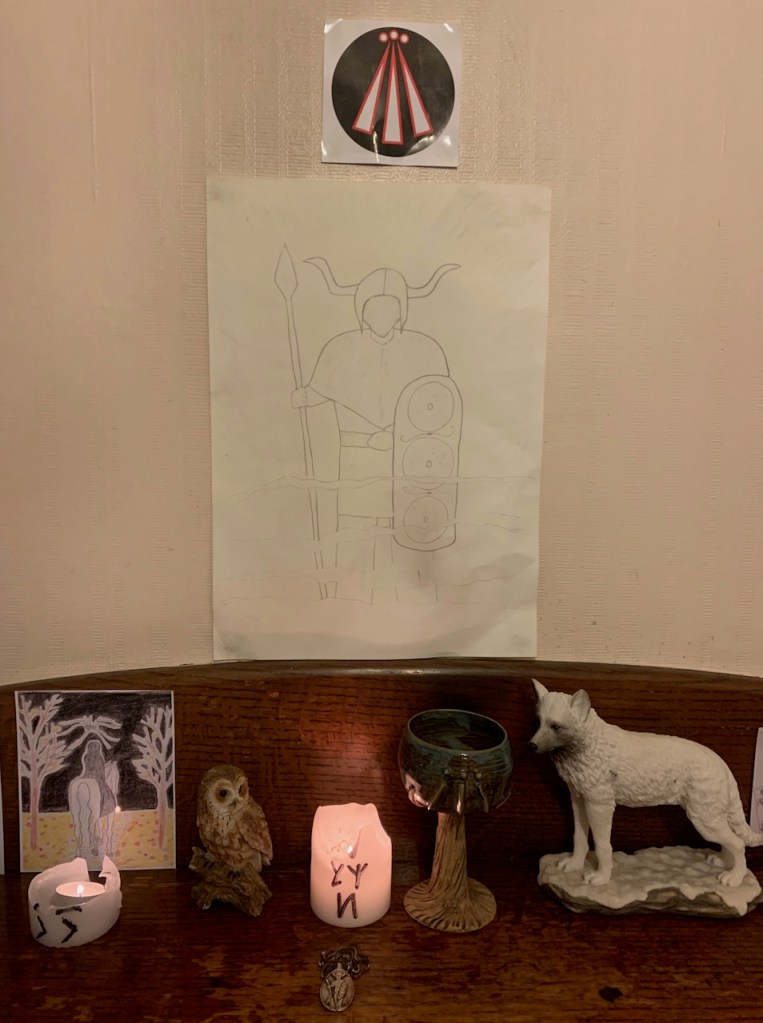

For me being able to withdraw, having a safe home, a room I have made into a sanctuary, being able to spend time in prayer and meditation with my Gods and guides is essential for enabling me to go out into the world and do the shamanic work in person and online I eventually hope to make a living from.

I believe the world would be a better place if there were more quiet spaces, more sanctuaries, more monasteries to provide the opportunity for withdrawal. If withdrawal was embraced and not pathologised.

Shamanic and meditative techniques are time-tested methods of dealing with overload and trauma and it is in helping others to practice them and providing safe spaces to do so that is where my current passion lies as a nun of Annwn.

Footnotes

(1) https://www.news-medical.net/health/Autism-History

(2) Grandin, Temple; Panek, Richard, The Autistic Brain, (Ebury Publishing, 2014), p12

(3) Ibid., p121

(4) Ibid., p36

(5) Ibid., p41 – 42

(6) Kolk, Bessel van der. The Body Keeps the Score, (Penguin Books, 2014), p60 – 61

(7) Grandin, Temple; Panek, Richard, The Autistic Brain, (Ebury Publishing, 2014), p97 – 100

(8) Buhner, Stephen Harrod. Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, (Inner Traditions, 2014) p31-33

(9) Ibid. p 33

(10) Kolk, Bessel van der. The Body Keeps the Score, (Penguin Books, 2014), p206

(11) Ibid, p97

(12) Ibid., p63-64

(13) Ibid., p207-208

(14) Buhner, Stephen Harrod. Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, (Inner Traditions, 2014), p48

(15) Ibid. p43

(16) Ibid. p59

(17) Grandin, Temple; Panek, Richard, The Autistic Brain, (Ebury Publishing, 2014), p98