Introduction – Who Lives On?

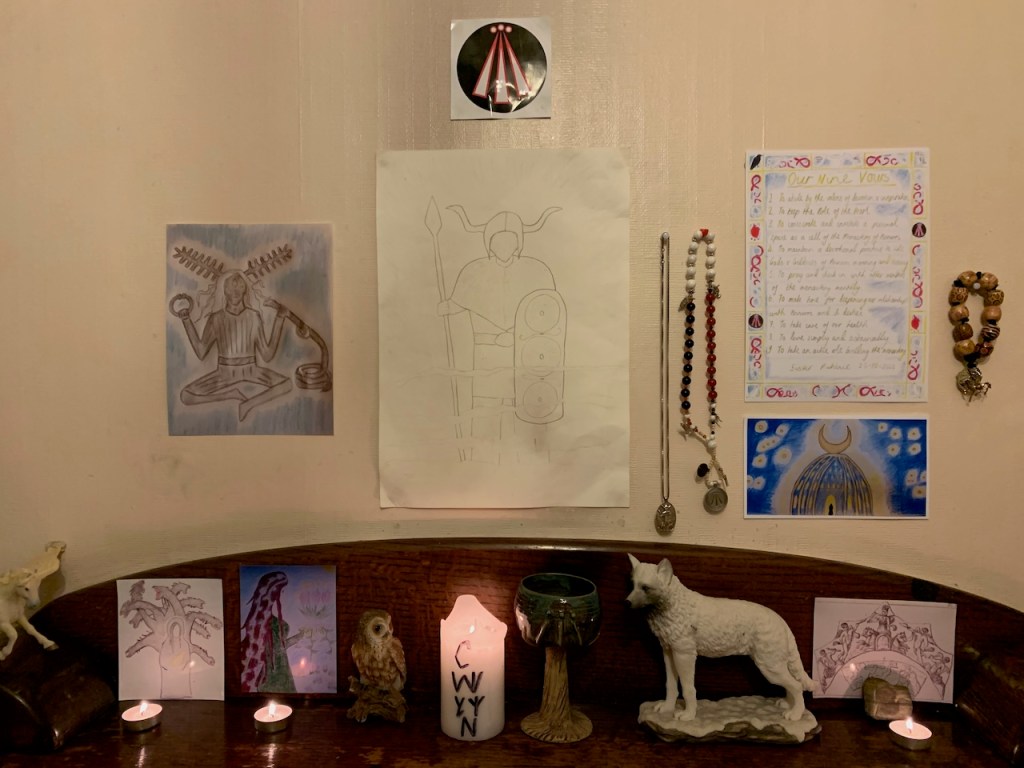

In ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, Gwyn, a ruler of Annwn and gatherer of souls, speaks the following lines:

‘I was there when the warriors of Britain were slain

From the east to the south;

I live on; they are dead.’ (1)

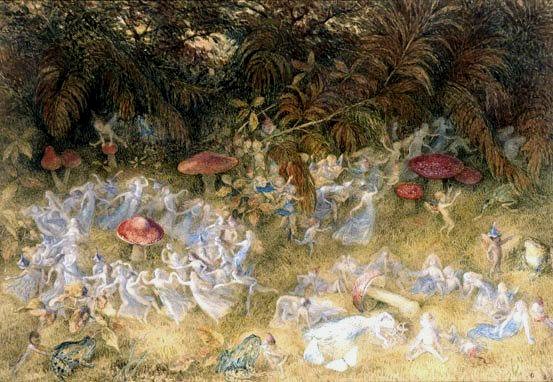

Here Gwyn draws a distinction between Himself living on and the mortal warriors who have died. He and His people, the spirits of Annwn or fairies, are immortal or at least very long-lived. Annuvian figures are often capable of returning from death (for example the Green Knight) and although there have been sightings of fairy funerals they are rare occasions of exceptional sadness.

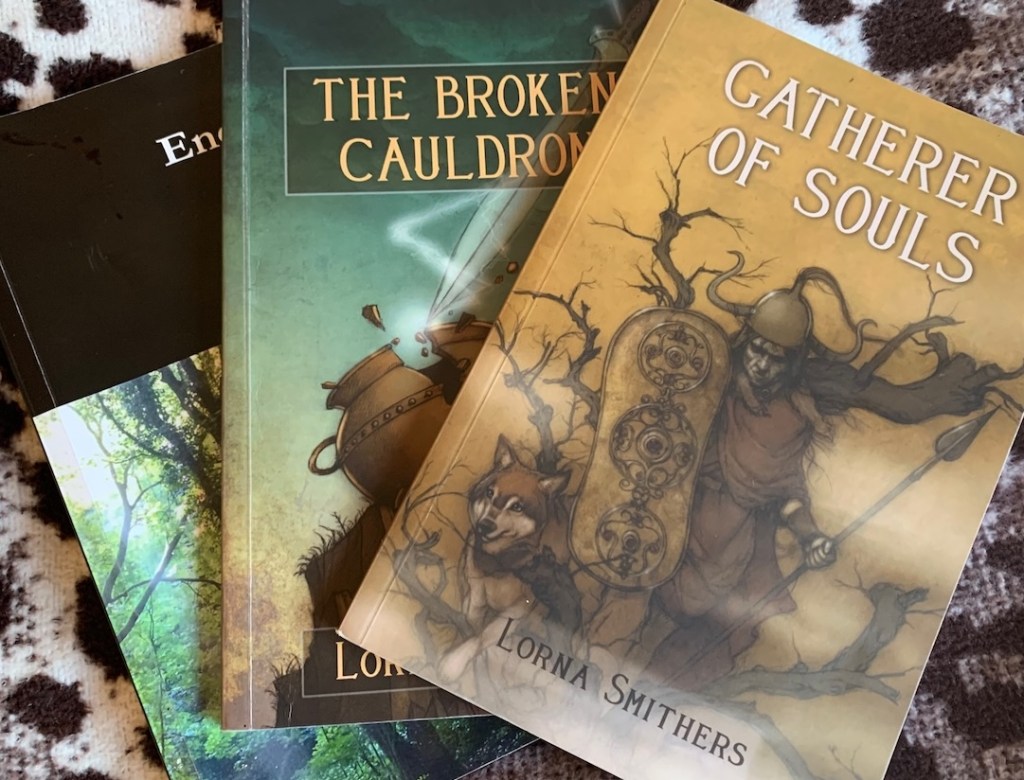

In my last two articles I argued that Annwn is primarily a world of the living to which Gwyn and His people guide the souls of the dead to be reborn from His magical vessel of rebirth – the Cauldron of the Head of Annwn.

I then cited evidence for certain souls, such as the souls of inspired bards and brave warriors, living on for longer and perhaps attaining immortality. In this article I will be examining other examples and exploring the reasons why some souls pass into new lives and others choose, or are chosen, to live on.

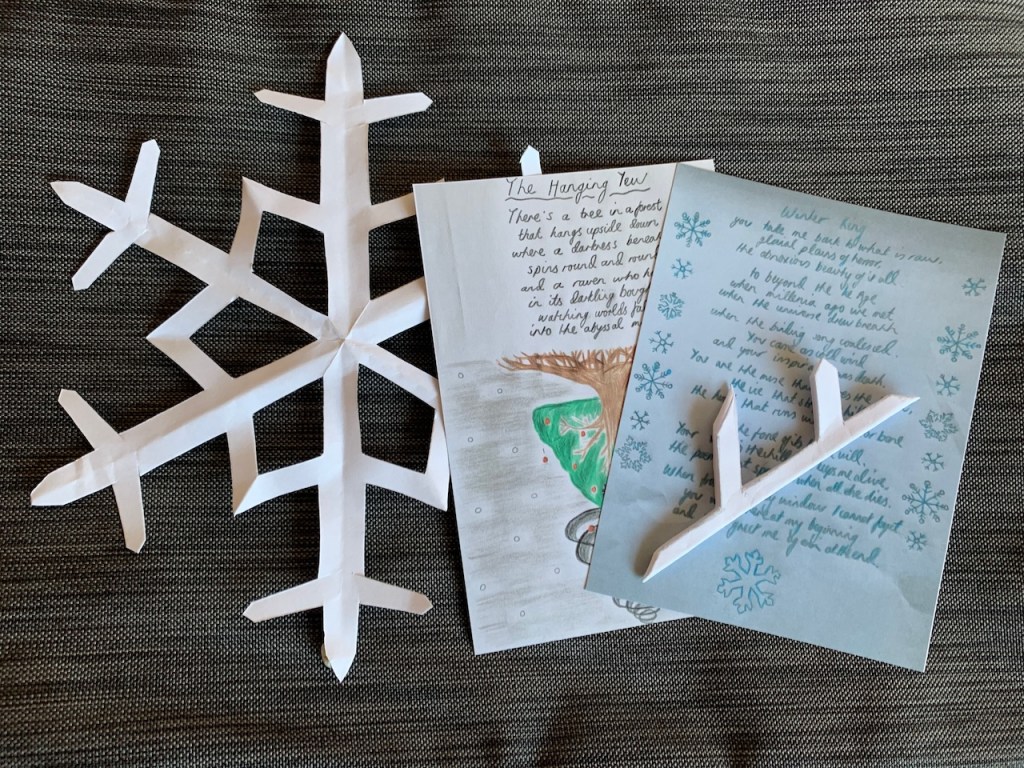

1. Inspired Bards

Previously I showed how Taliesin stole the awen from the cauldron and became ‘unfettered’ from the cycle of reincarnation as an inspired bard.

Taliesin claims his ‘native abode / is the land of the Cherubim’ and boasts of visiting the Court of Don and the fortresses of Gwydion and Arianrhod. (2) The abodes of the Children of Don are located in the landscape of Wales and in the stars. According to Charles Squire, the Court of Don is Cassiopea, Caer Arianrhod the Northern Crown, and Caer Gwydion the Milky Way. (3) Taliesin thus might be seen to join the immortal Gods feasting in the Heavens.

This might explain where he gained his ‘two keen spears: / from Heaven did they come’ (4) which he used to pierce the monsters of Annwn in ‘The Battle of the Trees’.

Taliesin brags about singing a ‘harmonious’ song in Caer Siddi ‘The Fairy Fort’. Considering he raided this Annuvian fortress one wonders whether this was a victory song he is claiming is superior to the songs of the fair folk.

The long-lived, or immortal, spirit of Taliesin has been invoked and channelled by bards for many centuries and modern bards, such as Kevan Manwaring and Gwilym Morus-Baird continue this practice in the present day.

Yet Taliesin is not the only bard whose spirit continues to live on. Another well-known example is Myrddin (Merlin). After dying a three-fold death (5) at the hands of shepherds at the confluence of Pausalyl Burn and the river Tweed in Drumelzier he continues to prophecy from his grave at Aber Caraf.

‘He who speaks from the grave

Knows that before seven years

|March of Eurdein will die.

I have drunk from a bright cup

With fierce and warlike lords;

My name is Myrddin, son of Morvyn’. (6)

Myrddin spoke through me resulting in a poem called ‘Myrddin’s Scribe’. This happened at a time when I was researching his lesser-known story as the northern British wildman Myrddin Wyllt and he continues to speak to others. His northern origins have been investigated by a series of scholars from William Skene to Nikolai Tolstoy, Tim Clarkson and William A. Young. Only recently have they grown in public recognition enough to warrant the initial plans for the building of a ‘Merlin Centre’ at Moffat in Annandale. (7)

Other bards included with Taliesin amongst the Cynfeirdd ‘early poets’ who might live on include Talhaearn Tad Awen, Aneirin, Bluchbardd and Cian.

2. The Brave not the Cowardly

The Cauldron of the Head of Annwn ‘does not boil a coward’s food’ (8). This statement might be read on a number of levels. It could refer to the tradition of the champion’s portion, or the ‘food’ or ‘meat’ might be a metaphor for awen. Awen carries connotation of inspiration and destiny which are breathed into a person by the Gods (9) at auspicious moments including rebirth.

An ambiguous image on the Gundestrup Cauldron might represent rebirth in either world. Are the warriors plunged headfirst into the cauldron by a deity with a hound, likely Gwyn, riding away to a mortal life in Thisworld or to join Him and His people, living on, perhaps forever, as magical huntsmen?

In the Norse myths the spirits of courageous warriors join Odin feasting in Valhalla. Might brave souls be similarly rewarded by joining Gwyn’s feast?

This is suggested in the writing of Pomponius Mela who records a druidic doctrine ‘commonly known to the populace so that warriors might fight more bravely, that the spirit is eternal and another life awaits the spirits of the dead’. (10)

Our evidence comes from warrior cultures but there is no reason to restrict the concept of bravery to warriors. In my personal experience any person might be rewarded for their courage by joining Gwyn on His hunt and at His feast.

3. Speaking Heads

In the Second Branch of The Mabinogion after Bendigeidfran is slain in battle he asks seven survivors, including Pryderi and Taliesin, to cut off his head and to feast with it for seven years in Harlech and for eighty years in Gwales. He tells them, ‘And you will find the head to be as good company as it ever was when it was on me’. (11) True to his word, ‘Having the head there was no more unpleasant than when Bendigeidfran had been alive with them’. (12)

This is suggestive of Brythonic beliefs about the soul residing in the head and being able to live on there after death. It suggests Bendigeidfran’s spirit was so strong it played a role in delaying the process of decomposition (although there are other factors at play in the pausing of time such as the singing of the birds of Rhiannon and the door that should not be opened). His spirit lived on in his head after death for at least eighty-seven years, continuing to speak with and counsel the seven companions.

We find evidence of this belief amongst the neighbouring Gauls from Roman writers. Diodorus Siculus says in war: ‘They capitate their slain enemies and and attach the heads to their horses’ necks… The choicest spoils they nail to the walls of their houses just like the hunting trophies from wild beasts. They preserve the heads of their most distinguished enemies in cedar oil and store them carefully in chests. These they display proudly to visitors, saying that for this head one of his ancestors, or his father, or he himself refused a large offer of money. It is said some proud owners have not accepted for a head an equal weight in gold, a barbarous sort of magnimity. For selling the proof of one’s valour is ignoble, but to continue hostility against the dead is bestial’. (13)

This passage, evidencing the tradition of head-hunting, is also suggestive of the belief the soul lives on in the head. More darkly it shows the dangers of one’s head being taken and one’s spirit living on in servitude to one’s enemies through the practice of embalming. This may be why Bendigeidfran was so keen for his people to take his head away before his enemies stole it.

Bran finally asked for his head to be buried under the Brynfryn ‘White Hill’ in London facing towards France. From thereon it served an atropaic function: ‘for no oppression would ever come from across the sea to this island while the head was in that hiding place’. (14)

4. Bog Heads and Bog People

The tradition of the living head is evidenced by the bog heads recovered from the mosslands of present-day Lancashire and Cheshire, which were inhabited by the Setantii, ‘the Reaping People’, at the time of their burial.

On Pilling Moss district was found ‘the head of a female… wrapped in coarse yellow cloth, with strings of beads. She is described as having a great abundance of hair, of a most beautiful auburn, which was plaited and of great length’ with a necklace of jet beads with ‘one large round amber bead’. (15)

Other bog heads include another female with plaited hair from Red Moss and male heads from Lindow Moss, Ashton Moss, Worsley, Briarfield and Birkdale. (16)

Peat bogs, known as mosslands in the north, are formed from Sphagnum mosses, which hold large amounts of water and break down to form peat. They provide anaerobic environments which prevent decay and are heavy in tannins, which preserve organic materials, including skin and organs.

The Setantii were likely well aware of these magical properties and placed the heads of their ancestors in the bogs so they continued to live on, like the head of Bendigeidfran, offering counsel and / or defending their territories.

We sometimes also find whole bog bodies such as Lindow Man and Seascale Man. Lindow Man died a ritualised three-fold death (like Myrddin). (17). This ritual killing has been read as a sacrifice to the Gods for aid in battle and as punishment for a criminal but might alternatively be read as a rite which bound his spirit in his body so he would live on.

His treatment prior to his death, such as the trimming of his moustache, the manicuring of his fingernails and his consumption of a griddle cake baked from wheat, barley and weed seeds and food, drink or medicine containing mistletoe pollen (18) are suggestive of preparation for a special fate, perhaps living on as a guide, for which he was chosen by his tribe and / or by the Gods.

5. The Venerable Dead

Prehistoric burial mounds look very much like houses for the dead. Indubitably they were created to appear this way for this reason. Thus it might be suggested that the spirits of the dead were believed to abide there or to return there at specific times in order to counsel the living.

Burials with grave goods, which include all the accoutrements needed in life, such as clothing, armour, weapons, games, jewellery, make-up sets, eating equipment and food, show the soul is believed to live on after death.

A number of suggestions about what it did in the afterlife might be made. Perhaps the soul was seen to reside in the burial mound or to move on to the Otherworld or perhaps it was able to move between the worlds at will.

That the soul remained in the mound or sometimes returned is suggested by the evidence of ritual feasts that might have taken place at liminal times such as Nos Galan Gaeaf when the veils between the worlds were thin. This way venerable ancestors might have lived on as counsellors and guides.

6. The Angry and Vengeful Dead

Whereas there were some persons who were chosen to live on there were others who certainly were not – enemies, criminals, the angry and vengeful.

Whilst some severed heads were placed in a bog to preserve the facial features of an ancestor some heads were mutilated perhaps with the intent of preventing the spirit from residing in the skull. Examples include the head from Briarfield which was ‘deposited in a defleshed state without the mandible’ and four defleshed skulls from the Thames. (19) The disarticulation of corpses and their binding (20) might have served a similar function. These practices suggest some spirits who lived on might have been powerful enough to raise their bodies and return physically from the dead.

Will Parker associates such dismemberments with the ‘devils’ of Annwn who are contained by Gwyn ap Nudd to prevent the destruction of the world. (21)

7. Witches of Annwn

Another group of individuals who were relentlessly persecuted and the likes of Arthur and his warriors seriously did not want to live on were the witches of Annwn.

This term appears in the poetry of Dafydd ap Gwilym:

‘Unsightly fog wherein the dogs are barking,

Ointment of the witches of Annwfn.’ (22)

It refers to a Gallo-Brythonic tradition of magic-workers whose powers and inspiration came from Annwn. Their practices are recorded on ritual tablets from ancient Gaul. On the Tablet of Chamalieres (50 AD) a group of male magic-workers invoke the Andedion ‘Underworld God(s) / Spirits’, Maponos and Lugus for aid in battle and the Tablet of Larzac (90 AD) records the ‘prophetic curse’ of a group of female ‘practitioners of underworld magic’. (23)

Others existed in ancient Britain for example the black-robed women who defended Anglesey from the invasion of the Romans with the Druids in the account of Tacitus. ‘Women in black clothing like that of the Furies ran between the ranks. Wild-haired they brandished torches. Around them, the Druids, lifting their hands to the sky to make frightening curses frightened (the Roman) soldiers with this extraordinary sight. And so (the Romans) stood motionless and vulnerable as if their limbs were paralysed’. (24)

The Christian persecution of these uncanny figures is recorded in our myths. At the end of Peredur son of Efrog the eponymous ‘hero’ slays the nine witches of Caer Loyw. A witch is killed in a specific way. ‘Peredur drew his sword and struck the witch on the top of the helmet, so that the helmet and all the armour and the head were split in two’. (25) The splitting of the head may be a ritual maneuver to prevent a witch’s soul from living on.

Arthur kills Orddu, ‘Very Black’, a hag who lives in a cave ‘in Pennant Gofid in the uplands of Hell’ in a similar manner. ‘Arthur… aimed at the hag with Carwennan, his knife, and struck her in the middle so she was like two vats.’ (26) Her severing in twain was likely intended to serve the same function.

From personal experience I know Arthur’s ploy was unsuccessful. On her death Orddu joined the spirits of Annwn and lives on with her mother, Orddu, and other witches of Annwn as guides to the magical tradition of the Old North.

Conclusion – To Live On or Not to Live On?

In this essay I have shown that certain persons choose, or are chosen by their people and / or the Gods to live on after death. It is likely they were chosen for personal qualities such as inspiration, bravery and wisdom to become ancestral guides with whom their people could commune.

On the other hand people went to great lengths to prevent the vengeful dead from returning. One example, from the not so distant past, is the burial of the ‘witch’ Meg Shelton face down with a boulder on top in St Anne’s graveyard in Woodplumpton, not far outside Preston, near my home, in 1705.

In ancient Britain, in a polytheistic society, in which the people lived in constant communion with the Gods and spirits there would have been a much deeper awareness of the processes surrounding whether a spirit lived on along with a knowledge of the rites for maintaining and dismissing their presence.

As the old ways return the question arises who amongst us might choose or be chosen to live on and, if given the choice, what answer we might give.

- Hill, G. (transl), ‘The Conversation between Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, Awen ac Awenydd

- Parker, W. (transl), The Mabinogion, (University of California Press, 2008), p173

- Squire, C. Celtic Myth and Legend, (1905), p252-3 https://sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/cml/index.htm

- Haycock, M. (transl), Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007), p183, l187-188

- He is beaten with stones, tumbles into the water and drowns, and is impaled on a stake. E. Lawrence, ‘Threefold Death and the World Tree’, Western Folklore, Vol. 69, No.1, p92

- Jones, M. ‘A Fugitive Poem of Myrddin in his Grave’, Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective, l1-6, https://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/h02.html

- Breen, Christie, ‘September date for Merlin study release’, DnG, https://www.dng24.co.uk/september-date-for-merlin-study-release/

- Haycock, M. (transl), Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007), l17

- Awen shares a similar root to awel ‘breath’ and the cauldron is kindled by the breath of nine maidens – likely Morgana and Her sisters.

- Koch, J. The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, 2003), p32

- Davies, S. (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007), p32

- Ibid. p34

- Koch, J. The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, 2003), p13

- It remained there until it was dug up by Arthur – one of ‘Three Unfortunate Disclosures’. Davies, S. (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007), p34, p237

- Lamb, J. ‘Lancashire’s Prehistoric Past’ inSever, L. (ed.), Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, (The History Press, 2010), p27

- Barrowclough, D. Prehistoric Lancashire, (The History Press, 2011), p206

- He was hit on the head, garroted, then he drowned in the bog.Joy, J. Lindow Man, (The British Museum Press, 2009), p38 – 44.

- Ibid. p29

- Barrowclough, D. Prehistoric Lancashire, (The History Press, 2011), p209

- Ibid. p205

- Parker, W., The Four Branches of the Mabinogi, (Bardic Press, 2005), p645

- Gwilym ap, D. Poems, (Gomer Press, 1982), p134

- Koch, J. The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, 2003), p1-3

- Ibid. p34

- Davies, S. (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007), p102

- Ibid. p213

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aldhouse Green, M., Dying for the Gods: Human Sacrifice in Iron Age and Roman Europe (The History Press, 2002)

Barrowclough, D. Prehistoric Lancashire, (The History Press, 2011)

Breen, Christie, ‘September date for Merlin study release’, DnG, https://www.dng24.co.uk/september-date-for-merlin-study-release/

Cooper, A., Garrow, D., Gibson, C., Giles, M., Wilkin, N. Grave Goods: Objects and Death in Later Prehistoric Britain, (Oxbow Books, 2022)

Davies, S. (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007

E. Lawrence, ‘Threefold Death and the World Tree’, Western Folklore, Vol. 69, No.1, p92

Fahey, R. ‘Mystery of 80 bound skeletons found in mass grave explained by items found with their remains’, The Mirror, (2021)

Guest, C. (transl), The Mabinogion, (1838)

Gwilym ap, D. Poems, (Gomer Press, 1982)

Haycock, M. (transl), Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007)

Hill, G. (transl), ‘The Conversation between Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, Awen ac Awenydd

Hughes, K. 13th Mt Haemus Lecture: Magical Transformation in the Book of Talieisn and The Spoils of Annwn, (OBOD, 2019)

Jones, M. ‘A Fugitive Poem of Myrddin in his Grave’, Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective

Joy, J. Lindow Man, (The British Museum Press, 2009)

Koch, J. The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, 2003)

Morus-Baird, G. Taliesin Origins, (Celtic Source, 2023)

Sever, L. (ed.), Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, (The History Press, 2010)

Squire, C. Celtic Myth and Legend, (1905), p252-3 https://sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/cml/index.htm