‘Gwyn ap Nudd… he went between sky and air.’

Peniarth MS. 132

Have you heard them howling through the skies?

Have you heard them howl of distant worlds?

Have you felt the howling fear you’ll die?

Have you feared they’re howling for your soul?

If you have, your soul is no longer yours, my friend,

It has never been and will never be until the end.

And never is never as the howling winds

That carry us between sky and air.

Dormach and Death’s Door

Gwyddno Garanhir (‘Crane-Legs’) stands in a misty hinterland before the divine warrior-huntsman and psychopomp Gwyn ap Nudd (‘White son of Mist’) and his white stallion, Carngrwn.

Beside Gwyn is Dormach, his hunting dog, ‘fair and sleek’ and ruddy-nosed. Dormach’s gaze is commanding. His nose shines like a torch-fire; a beacon; a setting sun. Although he appears as a dog his shape somehow exceeds dog-like proportions. Gwyddno says:

‘Dormach red-nose – why stare you so?

Because I cannot comprehend

Your wanderings in the firmament.’

Gwyddno’s sensory perception is distorted. Dormach is close enough for his nose to be seen yet distantly wandering across the heavens.

This is due to the misty shape-shifting nature he shares with Gwyn. J. Gwengobryn Evans tells us Dormach ‘moved ar wybir, i.e. rode on the clouds which haunt the mountain-tops.’ ‘Wybir‘ is ‘condensed floating white cloud’ referred to as Nuden and ‘serves as a garment for Gwyn.’

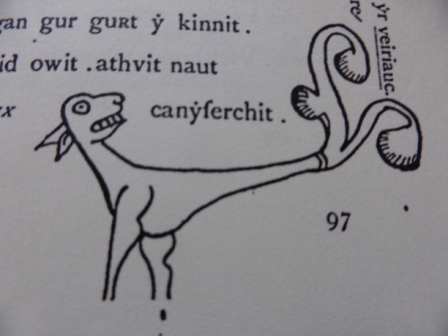

In a remarkable image beside the poem, Dormach appears as a strangely grinning dog with forelegs but instead of back legs he possesses two long and tapering serpent’s tails! This illustrates Dormach’s capacity to be near and distant and shows he is clearly not of this world.

From J. Gwenogbryn Evans, The Black Book of Carmarthen, (1907)

Dormach is a member of the Cwn Annwn (‘Hounds of the Otherworld’) who are sometimes known as Cwn Wybyr (‘Hounds of the Sky’). They occupy a liminal position between the worlds and play an important role in the passage of souls.

This is represented beautifully by John Rhys’ translation of Dormach (re-construed as Dormarth) as ‘Death’s Door’. He links this to the Welsh paraphrase for death Bwlch Safan y Ci ‘the Gap or Pass of the Dog’s Mouth’, the English ‘the jaws of death’ and the German Rachen des Todes and suggests Dormach’s jaws are the Door of Annwn. Although this translation is disputed by scholars it possesses poetic truth. Death is not an end but a passage to the next life.

Gwyddno’s passing is not depicted in ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’. I’ve been meditating on this poem for several years and had a break-through when I realised Gwyddno’s epithet, Garanhir, was an indicator of his inner crane-nature.

In a personal vision following from the poem Gwyddno donned his red crane’s mask, grew wings and followed the red sun of Dormach’s nose to be re-united with his kindred on an island of dancing cranes in Annwn.

Transformation

Physical death is not always a prerequisite of passage to Annwn. This is shown in the story of Pwyll and Arawn in the First Branch of The Mabinogion. Pwyll’s life-changing encounter with a King of Annwn called Arawn is heralded by the ‘cry of another pack’.

Although Pwyll notices Arawn’s hounds are ‘gleaming shining white’ and red-eared he fails to recognise their otherworld nature. He commands his pack to drive them off their kill: a grand stag, and feasts his own pack on it.

As recompense Arawn asks Pwyll to take his form and role in Annwn and fight his ritual battle against his eternal foe: Hafgan. By defeating Hafgan and resisting the temptation to sleep with Arawn’s wife, Pwyll wins the title of Pwyll Pen Annwn (‘Pwyll Head of Annwn’).

In the liminal space opened by the cries of Arawn’s hounds, Pwyll does not die but is transformed. Where passage to Annwn does not demand physical death it demands the death of one’s former identity and birth of a new one in service to the powers of Annwn.

Cwn Annwn

In later Welsh folklore Cwn Annwn are known by a number of names: Cwn Wybyr, Cwn Cyrff ‘Corpse Dogs’, Cwn Toili ‘Phantom Funeral Dogs’, Cwn Mamau ‘Mother’s Dogs’, ‘Hell-Hounds’ and ‘Infernal Dogs’. Here we find an admixture of pagan and Christian folk beliefs.

Annwn is identified with hell, its gods with demons, and its hounds with hell-hounds. Christianity’s dualistic logic limits the transformative potency of encounters with Annuvian deities by reducing them to objects of fear and superstition.

Yet the lore of Cwn Annwn endures with startling vivacity. They are famed for barking through the skies pursuing the souls of the dead. Therefore to hear them is a death-portent. They often fly the ways corpses will follow: hence their associations with teulu (‘phantom funerals’).

Their magical and disorientating qualities prevail. The 14th C poet Dafydd ap Gwilym speaks of encountering ‘the dogs of night’ whilst lost in ‘unsightly fog’ after hearing Gwyn’s ‘Crazy Owl’. In a report from Carmarthenshire the closer Cwn Annwn get the quieter their voices until they sound like small beagles. The further away the louder their call. In their midst the ‘deep hollow voice’ of a ‘monstrous blood hound’ is often heard.

Like Dormach they delight in a Cheshire-cat-like ability to shift their shape. Some appear as white dogs with red ears or noses. One is a ‘strong fighting mastiff’ with a ‘white tail’ and ‘white snip and ‘grinning teeth’ able to conjure a fire around it. Others are ‘the size of guinea pigs and covered with red and white spots’, ‘small’, ‘grey-red or speckled’. Some are ‘mice or pigs’.

At Cefn Creini in Merioneth they are accompanied by a ‘shepherd’ with a black face and ‘horns on his head’ who sounds remarkably like Gwyn: a horned hunter-god who blacks his face. He is supposedly fended off with a crucifix. In certain areas of Wales the ‘quarry’ of Gwyn and the Cwn Annwn is restricted to the souls of ‘sinners’ and ‘evil-livers’.

Gabriel Ratchets

In northern England we find the parallel of Gabriel Ratchets. Although they are nominally Germanic and rooted in the Wild Hunt there are striking resemblances with Cwn Annwn.

According to Edward A. Armstrong ‘Ratchet’ derives from the ‘Anglo-Saxon raecc and Middle English… rache, a dog which hunts by scent and gives tongue’. Rachen also means jaws: we recall ‘Rachen des Todes’ ‘Jaws of Death’.

In Yorkshire they are known as ‘gabble-ratchets’. Armstrong says ‘Gabble’ is a corruption of ‘Gabriel’ and ‘is connected with gabbara and gabares, meaning a corpse’. We find similarities with Cwn Cyrff ‘Corpse-Dogs’.

Gabriel Ratchets are also defined as packs of dogs barking through the skies portending death. Intriguingly they are identified with noisy flights of nocturnal birds who sound like beagles. In Lancashire James Bowker equates them with ‘whistling’ Bean Geese* flying over lonely moors.

In Burnley, Gabriel Ratchets are connected with the Spectre Huntsman of Cliviger Gorge. A maiden called Sibyl hears ‘wild swans winging their way above her’ before she is swept through the air by a ‘demon’. Poet Philip Hamerton shares the evocative lines ‘Wild huntsmen? Twas a flight of swans, / But so invisibly they flew.’

Thousands of Bewick’s swans and Pink-footed Geese arrive to over-winter on Martin Mere between September and November: the time ‘the Wild Hunt’ flies and may form the root of these Lancashire legends.

In Nidderdale the Gabble Ratchet is equated with the ‘night-jar, goat-sucker, screech-owl, churn-owl, puckbird, puckeridge, wheelbird, spinner, razor-grinder, scissor-grinder, night-hawk, night-crow, night-swallow, door-hawk, moth-hawk, goat-hawk, goat-chaffer… and lich-fowl’

We also find the ‘Ratchet Owl’: the ‘death-hound of the Danes’ and ‘night crow’: ‘This kind of owl is dog-footed and covered with hair; his eyes are like the glistering ice; against death he uses a strange whoop.’

Gabble Ratchets also take the form of birds with burning eyes and appear to warn of death. In some cases they are identified with the souls of un-baptised children.

Cwn Annwn and the Passage of Souls

In stories of Cwn Annwn and Gabriel Ratchets we find an astonishing menagerie of imaginal ‘hounds’. These rich folk beliefs, rooted in wild moorlands and piping wetlands, were not extinguished by Christianity.

Industrialisation forced country dwellers into towns to work in factories. 12 hour shifts in ‘dark Satanic mills’ crushed imagination. Wild places disappeared with the wild mind beneath red bricks of housing developments and asylum walls of schools and universities and secular careers.

Yet through the concrete of office-blocks and head-phones of call-centres over the white-noise of television we still hear the Cwn Annwn howling. The harder we try to shut them out the louder they howl.

The stoppers in Death’s Door tremble as they bark back the liminal spaces where the gods of Annwn are encountered and souls are transformed.

An increasing number of people are encountering hounds and gods of Annwn and having their lives turned around. I met Gwyn at a local phantom funeral site when I was lost. Passing through Death’s Door with him confirmed the reality of the afterlife and has given me a deeper appreciation of life in thisworld.

As I have striven to uncover Gwyn’s forgotten mythos from the British landscape I have been unfailingly drawn to flight paths of migratory birds and recovering wetlands. Locally, the Ribble Estuary and Martin Mere; further afield, Nith’s Estuary and Caerlaverock, Glastonbury Tor and the Somerset Levels, Cors Fochno (‘Borth Bog’) in Maes Wyddno (‘Gwyddno’s Land’).

This has led me to believe that as Brythonic King of Winter Gwyn presides over wintering birds and the passage of souls. This seems significant at a time migratory birds are threatened by melting glaciers and drained wetlands and floods have wrecked havoc across the UK. Our fates are intrinsically linked.

One of the most powerful lessons trusting my soul to Gwyn taught me was it has never been my own. I have always been one of his pack, one of his flock passing between worlds between sky and air.

Swans over Nith Estuary

SOURCES

Charles Hardwick, Traditions, Superstitions and Folklore, (Chiefly Lancashire and the North of England) (1872)

Dafydd ap Gwilym, Rachel Bromwich (ed.), A Selection of Poems, (1982)

Edward A. Armstrong, The Folklore of Birds (1958)

Heron (transl.) ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ (2015)

Jacqueline Simpson and Steve Roud, A Dictionary of English Folklore, (2003)

James Bowker, Goblin Tales of Lancashire, (1878)

J. Gwenogbryn Evans, The Black Book of Carmarthen (1907)

John Billingsley, West Yorkshire Folk Tales, (2010)

John Rhys, Studies in the Arthurian Legend, (1841)

John Roby, Traditions of Lancashire: Volume 2 (1829)

John Webster, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, (1677)

Miranda Green, Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, (1998)

Philip Gilbert Hamerton, The Isles of Loch Awe and Other Poems of My Youth, (1855)

Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, (2007)

T. Gwynn Jones, Welsh Folklore and Folk-Custom, (1930)

Wirt Sikes, British Goblins, (1880)

Nottingham Evening Post, Monday 23rd August, 1937

*This seems odd as Bean Geese over-winter in south-west Scotland and Norfolk.

**With thanks to John Billingsley and Brian Taylor for providing some helpful pointers on Gabriel Ratchets, particularly sections from Edward A. Armstrong’s The Folklore of Birds.

A card which keeps recurring in my readings (I mainly use The Wildwood Tarot) is ‘The Three of Vessels: Joy’. It features two common cranes dancing and a third spreading its wings, rising into flight with three vessels; white, green and gold. Its meaning is welcoming ‘new life or good fortune’, ‘celebration within a communal group or family’ and ‘successful return after migration’. The reading points state it’s about being able to give ourselves permission to experience ‘authentic joy’ as a ‘gift from the universe’.

A card which keeps recurring in my readings (I mainly use The Wildwood Tarot) is ‘The Three of Vessels: Joy’. It features two common cranes dancing and a third spreading its wings, rising into flight with three vessels; white, green and gold. Its meaning is welcoming ‘new life or good fortune’, ‘celebration within a communal group or family’ and ‘successful return after migration’. The reading points state it’s about being able to give ourselves permission to experience ‘authentic joy’ as a ‘gift from the universe’.