I. The Princely Hound

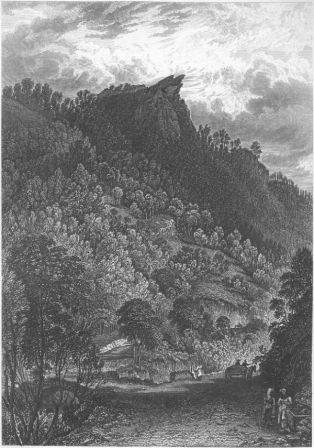

Maelgwn, ‘Princely Hound’, was the king of Gwynedd during the 6th century. His seat of rule was Deganwy on the Creuddyn Peninsula and his fortress overlooked the estuary of the river Conwy.

Maelgwn was a descendant of ‘the Men of the North’ from Manaw Gododdin, the area around Clackmannshire, which included Din Eidyn (Edinburgh). The old Welsh form of Gododdin, Guotodin, derives from the Iron Age tribal name, Votadini. No satisfactory translation has been made.

The Votadini came under Roman rule between 132 and 162 and remained allies with the Romans when they withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall, being awarded with the riches of the Roman lifestyle whilst maintaining independence. The names of Maelgwn’s ancestors, Tegid, Padarn, and Edern, were derived from the Latin names Tacitus, Paternus, and Aeternus, reflecting the pro-Roman sympathies of their lineage.

It seems likely this people worshipped a variety of local, tribal, and pan-Brythonic deities, along with those imported by the Romans. The name ‘Manaw Gododdin’ suggests they venerated Manawydan. A reference to Castle Rock as ‘Lleu’s Rock’ in the poem Y Gododdin shows Lugus/Lleu may also have been an important patron whilst the mention of Cynfelyn ‘Dog Heads’ slaughtered by Arthur at Din Eidyn could refer to a shapeshifting cult dedicated to a wolf/dog god such as Cunomaglos, Nodens/Nudd, or his son Vindos/Gwyn ap Nudd. Two statues of horned gods have been found in the area along with altars to Apollo, Sol, and Mithras at the Roman fortress at Inveresk.

It is impossible to pinpoint when the rulers of the Gododdin converted to Christianity. The religion began filtering into Britain and the 1st and 2nd centuries. The Roman Emperor, Constantine I, converted in 312 and began issuing penalties for pagan sacrifice in 324. Constantius followed in his footsteps by ordering the closure of temples ‘in all places and cities’ in 354 and Theodosius made Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire in 380. The burning of a temple to Jupiter Dolichenus at Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall in 370 suggests the pro-Roman rulers of Manaw Gododdin would have followed their Roman allies in converting during the 4th century.

It is likely that Maelgwyn’s great-great grandfather, Cunedda, ‘Good Hound’, who lived during the mid-fourth century, was Christian. Triad 81 names ‘Three Saintly Lineages of the Island of Britain’ and these include ‘the Lineage of Cunedda Wledig’. Intriguingly his name, however, contains traces of a totemic relationships with dogs and perhaps a patron relationship with a canine god.

In his History of the Britons (828) Nennius recorded that Cunedda went to Anglesey and drove out the Gaelic tribes:

‘62. The great king, Mailcun, reigned among the Britons, i.e. in the district of Guenedota, because his great-great-grandfather, Cunedda, with his twelve sons, had come before from the left-hand part, i.e. from the country which is called Manau Gustodin, one hundred and forty-six years before Mailcun reigned, and expelled the Scots with much slaughter from those countries, and they never returned again to inhabit them.’

Cadwallon, Maelgwyn’s father, completed the driving out of the Gaelic people and secured the kingdom of Gwynedd. Originally its name was Venedotia. Ven may be linked with Vindos, ‘White’, and Gwynedd seems to contain Gwyn’s name and his father’s (Nudd was also spelt ‘Nedd’, ‘Nidd’, ‘Nith’, ‘Neath’) although whether it was named after these old pagan hound-gods we’ll never know.

Maelgwn’s name refers both to his princely descent and ancient associations with dogs and dog-gods. Although he attempted to maintain the veneer of a civilised Christian ruler he could not shut out the deities of his land and lineage or his wilder impulses completely. He failed to keep the hounds and monsters of Annwn, within and without, at bay, and ultimately his soul was gathered by Gwyn.

II. The Dragon of the Island

Maelgwn was referred to as ‘high king’, which suggests he maintained a hegemony over other kingdoms. He collected tributes from Gwynllwg and led attacks on Dyfed and on the southern Britons.

Christian, like his ancestors, in some sources he was depicted as a generous supporter of Christianity, financing the foundation of Bangor for St Daniel and helping St Asaph build his church at Llanelwy. However, in many of the saints’ lives he was represented as a ‘great tormentor of the saints’, such as Brynach, Cadog, Curig, Cybi, and Mechyll. His grants of land and monetary donations resulted from his being discomfited by a miracle and making offerings as a sign of his forgiveness.

In a section in The Ruin of Britain (6th century) Gildas presented a damning portrait of Maelgwn and five other princes. He likened them to the beast in the Book of Revelation 13.2: ‘And the beast which I saw was like unto a leopard, and his feet were as the feet of a bear, and his mouth as the mouth of a lion: and the dragon gave him his power, and his seat, and great authority.’ Maelgwn was identified with the dragon who gave the beast power and was referred to as ‘the Dragon of the Island.’

‘And thou, the island dragon, who hast driven many of the tyrants mentioned previously, as well from life as from kingdom, thou last in my writing, first in wickedness, exceeding many in power and at the same time in malice, more liberal in giving, more excessive in sin, strong in arms, but stronger in what destroys thy soul – thou Maclocunus, why dost thou obtusely wallow in such an old black pool of crimes, as if sodden with the wine that is pressed from the vine of Sodom?’

He spoke of how Maelgwn committed to Christianity but was drawn instead to sin by the ‘crafty wolf’ and reverted to his ‘fearful vomit like a sick dog’. Rather than attending to the praises of God, his court was a ‘rascally crew yelling forth, like Bacchanalian revellers, full of lies and foaming phlegm’.

Gildas accused Maelgwn of killing his ‘uncle the king with sword, spear, and fire’ to gain power. He told of how, when Maelgwn decided to become a monk, this made his first marriage illicit. After his reversion he killed his wife, then his brother’s son, and took his young wife ‘in desecrated wedlock’.

Whether Gildas’ accusations were true remains uncertain. We do know Maelgwn had a first wife called Sanan with whom he had two children: Alser, and Doeg, and a second who was the mother of Einion and Eurgain. He also had an illegitimate son called Rhun with Gwallen, daughter of Afallach.

A raven watches from the opposite hill – do his or her ancestors know the truth?

III. The Silencing of the Bards

Maelgwn’s lacivious lifestyle was echoed in ‘The Story of Taliesin’ (16th century). Here we find a depiction of a bardic competition, a long-standing form of entertainment Maelgwn was most fond of.

Maelgwn was served by a circle of twenty-four sycophantic bards whose chief was Heinin Vardd. They showered him with praises saying no king was as great in ‘form, and beauty, and meekness, and strength’ and all the powers of the soul. They are described as ‘learned men, not only expert in the service of kings and princes, but studious and well versed in the lineage, and arms, and exploits of princes and kings, and in discussions concerning foreign kingdoms, and the ancient things of this kingdom, and chiefly in the annals of the first nobles; and also were prepared always with their answers in various languages, Latin, French, Welsh, and English… great chroniclers, and recorders, and skilful in framing verses, and ready in making englyns in every one of those languages.’

This echoes the structure of the bardic professions in the medieval court. Most important was the Pencerdd, ‘Chief of Song’, who held a special chair. Then there were twenty-four officers holding the position Bardd Teulu, ‘Poet of the Household’. It took nine years to train to be a qualified court poet.

It seems Maelgwn enjoyed hosting competitions, sometimes cruel, amongst his bards and fermenting trouble between them. In an instance recorded in a poem by Iorweth Beli he challenged them to swim from Arfon to Castell Caer Seion across the Conwy. ‘When they came to land the harpers were not worth a halfpenny’ because their strings had broken ‘while the poets sang as well as before’.

Elphin went to Maelgwn’s court at Deganwy to claim he had a better bard than the wise and skilful bards of Maelgwn and was consequently locked in a golden fetter. Taliesin then went to win him back.

In his opening poem Taliesin not only promised to silence Maelgwn’s bards, but to curse the king and his offspring:

And to the gate I will come;

The hall I will enter,

And my song I will sing;

My speech I will pronounce

To silence royal bards,

In presence of their chief…

I Taliesin, chief of bards,

With a sapient Druid’s words,

Will set kind Elphin free

From haughty tyrant’s bonds…

Let neither grace nor health

Be to Maelgwn Gwynedd,

For this force and this wrong;

And be extremes of ills

And an avenged end

To Rhun and all his race:

Short be his course of life,

Be all his lands laid waste;

And long exile be assigned

To Maelgwn Gwynedd!

Taliesin silenced the bards by sitting in a corner and playing ‘blerwm, blewrm’ with his finger on his lips. When each went to perform for the king this was the only thing they could do. Maelgwn derided them for their drunkenness and ordered a squire to hit Heinin on the head with a broom! This seemed to do the trick as Heinin was then able to tell Maelgwn that Taliesin had caused their indignity.

IV. A Most Strange Creature

Taliesin introduced himself as Elphin’s Chief Bard, told of his origins from ‘the summer stars’ and boasted of a long line of exploits and interactions with pagan and Christian figures – a common bardic practice.

Then, on a more sinister level, he began to invoke Annuvian monsters:

There is a noxious creature,

From the rampart of Satanas,

Which has overcome all

Between the deep and the shallow;

Equally wide are his jaws

As the mountains of the Alps;

Him death will not subdue,

Nor hand or blades;

There is the load of nine hundred wagons

In the hair of his two paws;

There is in his head an eye

Green as the limpid sheet of icicle;

Three springs arise

In the nape of his neck;

Sea-roughs thereon

Swim through it;

There was the dissolution of the oxen

Of Deivrdonwy the water-gifted.

This monster shares similarities with those Taliesin ‘pierced’ in ‘The Battle of the Trees: a great scaled beast, a black forked toad, and speckled crested snake, all of whom were eaters of human souls.

He then spoke a disturbing prophesy against Maelgwn:

A most strange creature will come from the sea marsh of Rhianedd*

As a punishment of iniquity on Maelgwn Gwynedd;

His hair, his teeth, and his eyes being as gold,

And this will bring destruction upon Maelgwn Gwynedd.

After Taliesin summoned the wind, a ‘strong creature’ ‘Without flesh, without bone, / Without vein, without blood, / Without head, without feet’ into Maelgwn’s hall, the terrified king released Elphin.

Only the walls of an older castle remain…

… and they are haunted by jackdaw bards.

V. The Long Sleep of Maelgwn

The ‘strange creature’ with golden eyes, hair, and teeth, who Taliesin prophesied would destroy Maelgwn, turned out to be Y Fat Velen ‘The Yellow Plague’ – a great pestilence which struck in 547.

In an attempt to avoid the plague he retreated to the church in Llan Rhos and shut all the windows and doors.

However, when he looked out through a hole, he saw Y Vat Velen, that terrifying gold-yellow beast, and fell into a long, long sleep.

His attendants waited for days. When they realised his silence had been too long for sleep they found him dead. Thus a saying originated: ‘Hir hun Faelgwn yn eglwys Ros’, ‘the long sleep of Maelgwn in the Church of Rhos,’ a sleep so long he never awoke.

Although Maelgwn shut himself away in a church he did not escape Y Vat Velen or Gwyn and the hounds of Annwn arriving to take his soul. Lines in ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ suggest that Dormach, Gwyn’s best hound, was present at Maelgwn’s death:

My hound is sleek and fair,

The best of hounds;

Dormach he is, who was with Maelgwn.

In this poem Gwyn recites the names of four Men of the North whose souls he gathered from the battlefield: Gwenddolau ap Ceidio, Brân ap Ywerydd, Meurig ap Careian, and Gwallog ap Llenog. Gwyddno was of northern origins and on the brink of death. Like these other Men of the North, the Princely Hound did not go to Heaven, but returned with the death hound to join his ancestors in Annwn.

According to some sources Maelgwn is buried in Llan Rhos Church near the south door and to others on Ynys Seiriol, ‘Puffin Island’.

*Morfa Rhianedd, ‘the Sea-strand of the Maidens’ is between Great and Little Orme’s Head near Llandudno.

SOURCES

A.O.H. Jarman (transl.), Aneirin – Gododdin, (Gomer Press, 1998)

Charlotte Guest, The Story of Taliesin, Sacred Texts, (1877)

Edward Dawson, ‘Tribal Names: Linguistic Analysis and the Origin of Gwynedd’

Eberhard Sauer, Fraser Hunter, John Gooder, Martin Henig, ‘Mithras in Scotland: A Mithraeum at Inveresk’, Britannia, Vol. 46,

Gildas, The Ruin of Britain, Tertullian.org, (1899)

Greg Hill (transl.), ‘The Conversation Between Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir, Awen ac Awenydd‘, (2015)

Greg Hill, ‘Lleu Llaw Gyfes… is that Lugus?’, Dun Brython, (2016)

Mererid Hopwood, Singing in Chains, (Gomer Press, 2004)

Nennius, History of the Britons, Gutenburg.org, (2006)

Peter Bartrum, A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000, (National Library of Wales, 1993)

Rachel Bromwich (ed), The Triads of the Island of Britain, (University of Wales Press, 2014)

Book of Revelation 13.2, King James Bible, Bible Gateway