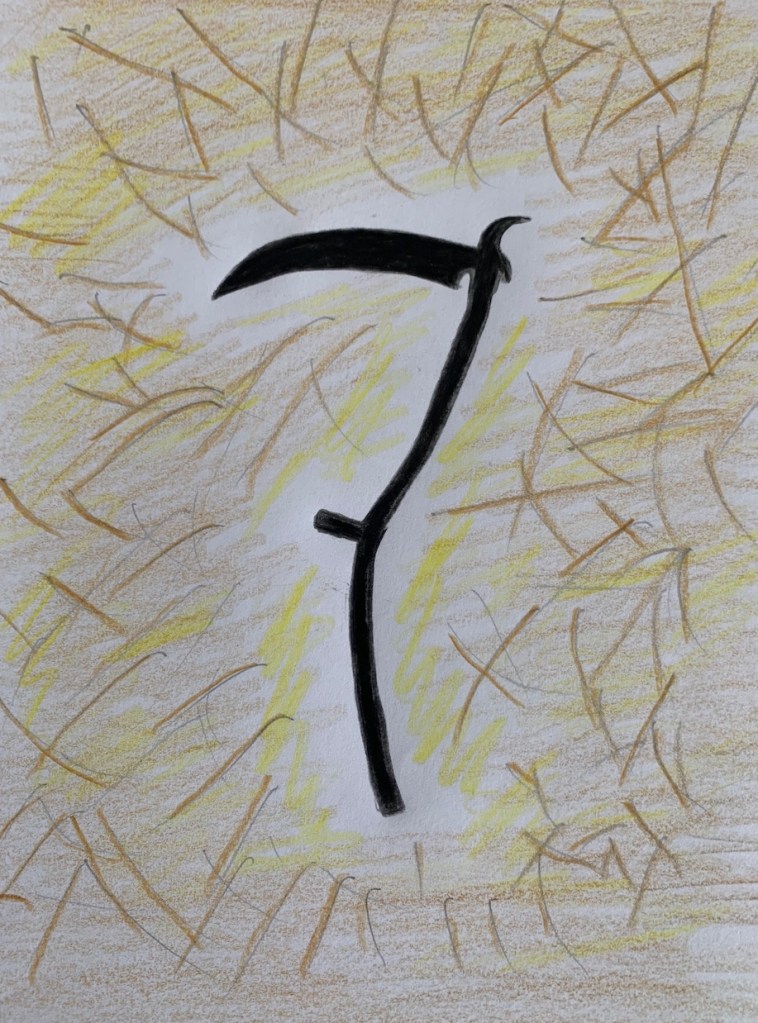

The wind is blowing. The Reaper is busy with His scythe. After my insights about being more of a hermit than a nun a whisper on the wind, ‘Sister Patience must die.’ Three years ago I took temporary vows by this name as a nun of Annwn and, as the time comes to renew them approaches, I realise I will not be taking them again this year. Instead I must surrender this name, this identity, disrobing over the next few weeks, then giving it entirely back to Gwyn, from whom it came, on His feast day on September the 29th. I have learned many lessons and received many blessings from this name. Hopefully some of the virtues of Sister Patience will live on as I return to my birth name and continue to serve Gwyn as a hermit and shamanic practitioner.

Tag: Death

Falling Leaves and Wanting to Live

A late autumn. Nos Galan Gaeaf passing. The leaves at last coming down in the fullness of their vivid vibrancy – the yellows of lime and maple and the bronzes of beech whilst the acers on the park shine their reds and oranges.

The trees are letting go. Surrendering. Preparing for sleep. Dying a kind of death.

I’m feeling well. As a result of my practices my physical and mental health is improving. Following an injury I’m running half marathons at my best pace yet.*

Yet, still, after being triggered by a reader’s comments on my book I’m turning the old cogs and being chewed up by an old destructive thought pattern. ‘If my readers don’t like my writing I will lose my audience, I won’t make any money, I will have to return to proper paid work and forfeit my time for spirituality and creativity, meaning my mental health will deteriorate, leaving me with the choice between a living death and death.’

For a few days I considered totally rewriting my book to fit better with what I thought those in my audience who are Celtic Polytheists and Druids might want or expect by removing some of the darker and more gory scenes that are based on my personal gnosis about the story of Gwyn/Vindos and His interactions with the serpents of Annwn but this led to total paralysis. I realised it wasn’t what He wanted and ultimately the book is for Him.

I then perceived I’d slipped back into the false belief I could make a living as a professional author, which I promised Gwyn I would give up over ten years ago, had thought I’d given it up, but was unconsciously still clinging onto it.

In a journey with the Way of the Buzzard Mystery School** I performed a rite of letting it go with puffin – viscerally vomiting it up as a huge and toxic fish.***

This done I’m still turning those darned cogs. ‘I can’t make a living from my writing so when my savings run out I will be faced with the choice between living death and death.’

Then, entirely expectedly, a voice from within, a voice from my healthy body, from my life force, from my spirit, ‘I WANT TO LIVE.’

This was utterly astonishing because, in my existing memory, I cannot remember once thinking ‘I want to live.’ Since I started primary school most of my life has been a battle against ‘wanting to die’ so this signals a vast change.

I believe this comes from having arrived at a monastic lifestyle that suits me centred around devotional creativity in service to my Gods. This incorporates practices that nourish my well being and relationship with Them such as meditation, journeywork, yoga, running, strength training and good nutrition (giving up alcohol has been a big factor) along with cleaning, gardening and litter picking as service to my home and local greenspace. It has also been a great help having the support of my spiritual mentor, Jayne Johnson.

I think my letting go ritual at this time of leaf fall also played a big role.

Much of my fear lies around having to give much of this up to earn a living when my savings run out. I haven’t found a solution yet but it seems a huge step forward to have my inner impulses on board, not to want to die but to live. To be recognising my negative thought patterns and stopping fighting myself.

Those cogs fixed in my mind by the capitalist system I smash, I trample, I cast down amongst the fallen leaves to rust, to rot, to die, so I can live.

*Last year’s PB was 1:54:55 and since recovering from my sciatic nerve injury I have bested it by nearly six minutes with 1:49:02 – well above average for a 42-year-old female.

**The Way of the Buzzard Mystery School website can be found HERE.

***The images from my journey book recording my journey with puffin.

Honouring the Death of Gwyn

How do you honour the death of your God?

This is a question many religions have an answer to. One of the most obvious is Christianity with the traditions surrounding the death of Jesus. Within Paganism and Polytheism rites have been developed for many Gods (often grain Gods) including Osiris, Tammuz and figures such as John Barleycorn.

When I started worshipping Gwyn ap Nudd over ten years ago I found out on Calan Mai He fights a battle against His rival, Gwythyr ap Greidol, for His beloved, Creiddylad. Although it isn’t explicit within the source material (1) parallels with other seasonal myths (2) suggest that Gwyn, as Winter’s King, is defeated by Gwythyr, Summer’s King (3) at the turn of summer, ‘dies’, and enters a death-like sleep. He then returns at summer’s end to take Creiddylad to Annwn and assert His rule as Winter’s King.

For most Pagans and Polytheists Calan Mai / Beltane is a fertility festival. The rites of dancing of the May Pole, and crowning of a May / Summer King and Queen have a basis in the sacred marriage of Gwythyr and Creiddylad.

Even before I realised I was asexual I always felt like an outsider on Calan Mai. Whilst I enjoyed the white flowers and verdant energy I never got into the full swing of the celebrations (at least not without a large amount of alcohol).

Then I met Gwyn and found out this was the time of His death. I have now come to understand why it is bittersweet – finding joy in the new growth on the one hand and feeling His loss and commending His sacrifice on the other.

‘From the blood of the King of Annwn

the hawthorn blossoms grow.’

Slowly, Gwyn has revealed to me visions of the mythos surrounding His death and ways of honouring it within my personal practice as a Polytheist.

It happens slightly differently every year but I present here a ‘core narrative’ and the rites by which I navigate this difficult time in my seasonal calendar.

On Nos Galan Mai I offer Gwyn a sprig of thyme for courage and recite my poem ‘If I Had To Fight Your Battle’ and then meditate on its meaning.

At dawn on Calan Mai I visit Him in spirit as He dons His armour and makes His way to ‘the Middle Ford’, Middleforth on the Ribble, which is the place within my local landscape where His battle takes place and there speak my farewells.

Later in the day I go for a walk and look out for signs of the battle of Gwyn and Gwythyr. I often see Them as warriors, animals, or dragons in the clouds. On one occassion I heard ‘We are the Champions’ playing at a May Day fair.

I place the sprig of thyme at the Middle Ford then look out for signs of Gwyn’s death.

Gwyn’s death takes place before dusk and I have felt it signalled by sudden cold, the coming of rain, and a feeling of melancholy. Once, when I was running, I got the worst stitch ever, like I’d been stabbed in the side, knew it was Gwyn’s death blow and received the gnosis His death was bad that time.

I pay attention to the hawthorn, a tree of Creiddylad’s, symbolic of Her return.

In my evening meditation I bear witness to Gwyn being borne away from the scene of battle by Morgana and Her sisters (4) who appear as ravens, crows, or cranes. They take Him and lay Him out in His tomb in the depths of His fortress in Annwn. His fort descends from where it spins in the skies (5) and sinks into the Abyss (6) to become Caer Ochren ‘the Castle of Stone’ (7).

I then join Morgana and Her sisters and other devotees from across place and time saying prayers of mourning for Gwyn and spend time in silence.

Three days later Morgana and her sisters heal Gwyn’s wounds and revive Him from death. This a process I have taken part in and was powerful and moving. He then remains in a death-like sleep over the summer months.

I would love to hear how other Polytheists honour the deaths of their Gods.

FOOTNOTES

(1) The medieval Welsh tale of Culhwch ac Olwen (11th C)

(2) Such as the abduction of Persephone by Hades in Greek mythology.

(3) Clues to Their identities as Winter and Summer Kings are found in their names Gwyn ap Nudd ‘White son of Mist’ and Gwythyr ap Greidol ‘Gwythyr son of Scorcher’.

(4) I believe Morgana and her sisters are Gwyn’s daughters through personal gnosis based on the associations between Morgana, the Island of Avalon, and Avallach, the Apple King, who I believe is identical with Gwyn and the possible identification of Morgan and Modron, daughter of Avallach.

(5) ‘the four quarters of the fort, revolving to face the four directions’ – ‘The Spoils of Annwn’.

(6) The existence of an Abyss in Annwn is personal gnosis.

(7) This name is not a direct translation (Marged Hancock translates it as ‘the angular fort’) but comes from Meg Falconer’s visionary painting of Caer Ochren ‘the cold castle under the stone’ in King Arthur’s Raid on the Underworld.

XII. Your Death

Day Twelve of Twelve Days of Devotion to Gwyn ap Nudd

I come this twelfth day

to consider Your death.

How I have seen You die

so many times yet that

You should die forever

is unthinkable, unbearable…

For when You have gathered

the last stars at time’s end

there will be no tears left,

no-one left to cry them,

and who would gather the

soul of the Gatherer of Souls?

In the May Snow

For Gwyn

I.

In the May Snow

I mourn for you.

Crack willow take

my soul again

to the raven’s

places of Annwn,

to where the bones

are old and grey.

II.

In the cold castle

lies your tomb

and on its corners

stand four cranes

to coax your soul

from death and gloom,

to sing you back

to life again.

Will You Leave?

Will the seasons continue to turn?

Will your battle still commence?

In these days of plague when

we need you so much

will you depart

to the land of the dead

to sleep in your cold castle

in Annwn?

~

The seasons must turn.

My battle must commence

and my death-blow must be struck.

Yet when I die you will see my ghost

and when I sleep I will sleepwalk.

Many will see the wolf of my soul.

Through these days of plague

I will guide the dead.

This poem is addressed to my patron god, Gwyn ap Nudd, on Calan Mai. Today Gwyn (Winter’s King) battles against Gwythyr (Summer’s King) for Creiddylad, a goddess of spring and flowers, and is destined to lose and return to sleep in the Castle of Cold Stone, in Annwn.

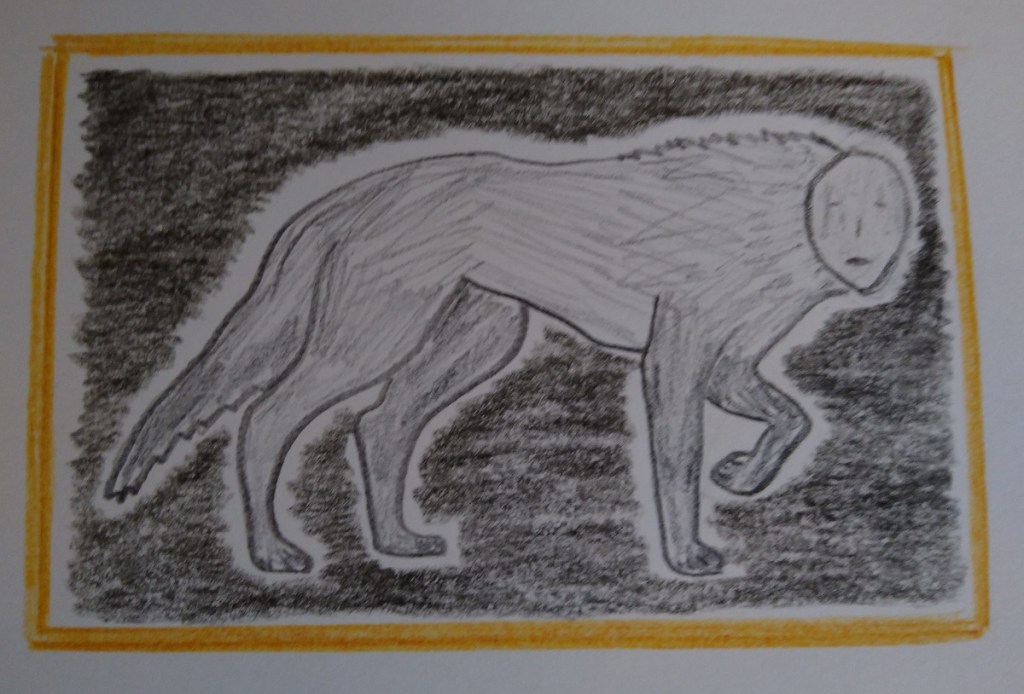

The Lean Wolf

approaches

with a little bit

of Chernobyl

in its deadly

stride.

A big black bell

is ringing inside it.

Its face is a man’s.

There is nothing

behind it.

I wrote this poem following a dream of which I remember little but the vivid image of a lean menacing wolf with a man’s face and the knowing because I’d seen it, been its presence, I was going to die.

I’ve had a handful of dreams in which I’ve had this gnosis. In one I was a captured soldier awaiting execution and Gwyn prepared me for death by telling me I must go into the hazel, and the beetle, and something I can’t recall. In another I was a clawed creature clinging to a lift descending to the abyss. And in another I was and was not a dark magician, who in a magical battle against mechanical forces, was cut into a thousand pieces by whirling blades and resurrected as a vampiric woman.

Through these dreams I know I have lived many lives, died many deaths, in Thisworld and in Annwn, and perhaps in worlds beyond. That a part of me, which I call my soul, carries these memories.

When I was talking to my dad about his funeral plans I was surprised to hear that he, like me a philosophy graduate, had never thought about whether he had a soul or what would happen when he died. He might have theorised about it but had never really contemplated what would happen to him.

Such questions have been on my mind as long as I can remember. Like my dad I theorised about them, attempting to find answers through philosophy, until I met Gwyn and he taught me to journey to Annwn. Until he and his father, the dream-god Nudd/Nodens, helped me to sleep and listen to my dreams.

For the first time since the Second World War people in Britain are suddenly facing death, due to the threat of the coronavirus. This is a complete unknown for people of my mum and dad’s generation, for mine, and the next generation, who might have included my children, if I’d had them.

I understand that one of the reasons Gwyn appeared in my life and taught me to journey was to help me prepare for death. I know a small handful of others who have had similar experiences with him and different gods, and of those who have gained their own understanding without experience of deity.

In contrast to the advice I’ve seen in various places to focus only on the positives, I believe at this time, when so many of us have so much extra time, there is no better time to contemplate the lean wolf.

Slowing Down

It happened when I was gearing up. Having given up my placement with Carbon Landscapes in Wigan as it was too office based I had returned to volunteering with the Lancashire Wildlife Trust closer to home and got the conservation internship at Brockholes.

One hundred per cent practical outdoor work, and just a 6 mile cycle ride away at a place I know and love, it promised to be my dream job. I’d completed my first 10k race in New Longton and was training for the City of Preston 10 miles. I was also preparing for my Taekwondo grading, on the Spring Equinox weekend, to gain my blue belt.

Then it struck. A series of lightning-like strikes. I’d heard the thunder. The first rumblings from China, the news the storm was getting closer, that it had hit Italy, Spain, France, arrived in the UK. We joked about it at first. Me with my perpetually runny nose, like a toddler, in spring, due to my hay fever. Anyone who coughed or sneezed, “I haven’t got coronavirus.” We’d seen it on the news but it didn’t seem real, like our little island with its green hills and fresh air granted some form of immunity. We’re British, right? We won the war. Then people started getting sick and started dying.

Around a fortnight ago hand washing or using antibacterial gel before eating became mandatory. On Monday the 16th of March when I was out with the Mud Pack at Brockholes the next step was stopping sharing PPE. No more slightly musty gloves from the collective stash. I was given my own hi-vis in preparation for beginning my internship on the Thursday. Still we worked together building a hibernaculum for great crested newts and ate our lunch outside on a day bright as coltsfoot.

On Tuesday the 17th of March we received an email saying we could no longer share lifts in the van or meet together inside. On Wednesday the 18th of March, another glorious spring day, I went out on another work party planting sarroccoca and eleganus amongst the daffodils on the rock garden on Avenham Park. There was little joking, even amongst the guys from Preston City Council, who were helping out. Everything felt ominous. Still, it came as a shock when I got home to find out all LWT volunteer work parties had been cancelled until the end of April along with my voluntary internship.

In some ways it was a relief because I live with parents who are over 70 and in ill health. I’d been torn between the choices, if I was to continue volunteering, of moving out or risking their lives. So I accepted it was for the best I isolated with them, just going out to do our shopping and to exercise.

Still, I was bitterly disappointed. After winning the struggle to give up alcohol and manage my anxiety without it, and feeling I was finally coming home from my exodus with Carbon Landscapes to the place and the job role in my local landscape where I truly belonged… this!

Yet, I also felt, in some ways my gods had been preparing me for it. If I hadn’t given up alcohol there is no way I would have coped with the situation or with the responsibility of looking after my parents. When considering whether to quit my placement I’d heard a clear voice telling me to “come home.”

Another point is that, at the beginning of January, after I had a mild attack of exercise-induced asthma as a consequence of running my fastest time of 25.21 for 5k on the Avenham Park Run, Gwyn told me during this Taekwondo belt (green with a blue tag representing growth toward the skies) I needed to ‘learn to breathe’. Since then I’ve been trying to discipline myself to spend time in stillness, focusing on my breath, in my morning and evening meditations, but not always managing it.

(What has struck me and many others is that breath is central to this situation on many levels. Coronavirus attacks the lungs and those who get seriously ill face a battle for their breath which, in some cases, can only be won with the aid of mechanical ventilators, and in others not at all. The places worst hit have been cities where the air is badly polluted. Now flights have stopped and most people have stopped commuting by car, the skies are clear of contrails and air pollution has dropped.)

At first, after all that gearing up, I felt like Wily Coyote poised in mid-air off the edge of a cliff with my legs still running. Over the past few days I have been striving to ground myself, to slow down, to process the changes, to find space to breathe. Not easy when surrounded by panic.

My first response was to hit the news and social media to find out what’s happening and what everyone’s doing, leading only to tight chest, shortness of breath. To rush to formulate my own words, to share poems addressing the situation. Like I have some kind of gods-given responsibility… whilst aware of adding to the din of others doing exactly the same and increasing the massive strain on the internet that we forget is causing air pollution as we don’t see the power stations.

“Slow down,” the message kept coming through, from the stopping of traffic the virus has caused. As I ran more slowly, no longer worried about beating my best times, happy to be in the moment, feet steady alongside the Ribble in time with her flow where the daffodils watch with sad beautiful faces.

“Slow down,” as I began to take my time in my parents’ garden instead of rushing through the tasks. Appreciating the sunlight on the pastel colours of the hyacinths and the scent of the magnolia, the steady chuck of spade in earth and textures of compost from the bottom of the heap rich from years of decay.

“Slow down,” every time I sat before my mantlepiece in my bedroom where I keep altars to my deities, feathers and stones, to which I’ve recently added photos of my family ancestors knowing I’ll need their help.

I had developed a new routine based around prayer, writing, housework, gardening, shopping, and exercise when lockdown struck. It didn’t hit too hard as I was already living under those rules.

I’m anticipating a greater slowing. Right now I feel like I’m in ‘defence mode’ with my main prerogatives being to tend to the needs of and protect my vulnerable parents and to maintain my own health. I have also offered to run deliveries on my bike for family and friends, including the older members of my poetry group, if they end up isolating either due to illness or the government order.

An important point of support has been the Way of the Buzzard Mystery School online journey circles and coaching calls. I have been involved with Jason and Nicola’s drumming circles at Cuerden Valley and the Space to Emerge camp since they began and have appreciated being able to continue getting together to do journeywork and discuss the current situation from a shamanistic perspective.

With my daily routine and a support network in place I’m hoping for the best and preparing for the worst. If the UK follows Italy’s curve it is possible that my friends, family, and myself, may be not only be slowed down but locked away by illness, that we may be halted by the life-or-death battle for our breath. That we may have to face the final stopping – death – as usual a topic few think or talk about.

I’ve long had a plan for my funeral but am aware it will be invalidated by these circumstances. There is a huge lack of information about what will happen to the bodies of those who die of coronavirus in the UK. How they will be dealt with, where they will go, how their passing will be acknowledged.

Yet this great slowing gives us time to pause for thought – about the fears we’d rather not face and the solace we can find in each moment of these spring days so beautifully bright in contrast.

Breathe

‘We need to remember that our very breathing is to drink our mother’s milk – the air – made for us by countless microbial brothers and sisters in the sea and soil, and by the plant beings with whom we share the great land surfaces of our mother’s lustrous sphere.’

Stephan Harding

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Respiration (from spirare ‘breath’ and re ‘again’) is participation.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Lungs. Two. Right and left. Each enclosed in a pleural sack in the thoracic cavity of the chest. Primary bronchus, secondary bronchi, tertiary bronchi, terminal bronchiole. In the alveoli, ‘little cavities’, across the blood-air barrier, gas exchange takes place.

Breathe in: oxygen 21%, carbon dioxide 0.04%. Breathe out: oxygen 16%, carbon dioxide 4.4%. 6 carbon glucose, oxidised, forms carbon dioxide. Product: ATP (adenosine triphosphate) ‘the molecular unit of currency of intracellular energy transfer’. The spark of all life.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Respiration (from spirare ‘breath’ and re ‘again’) is participation.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Birds have lungs plus cervical, clavicular, abdominal, and thoracic air sacs. Hollow-boned they are light as balloons, breathing in, breathing out. Then there are the lungless. Through tiny holes in the abdomen called spiracles leading to the trachea, insects fill their air sacs. Earthworms and amphibians breathe in and out through moist skins. Fish breathe water in through gulpy mouth breathe it out through gapey gills.

Plants breathe through their leaves. By daylight they photosynthesise. Stomata breathe carbon dioxide. It mixes with water. The green lions of chlorophyll work their magic by sunlight. Oxygen is released. From glucose the magical hum and buzz of ATP. At night they respire glucose and oxygen back to carbon dioxide and water. 10 times more oxygen produced than used.

Underground fungi breathe the air of the soil through thread-like hyphae that mass as mycelia. They respire aerobically (with oxygen) or anaerobically (without oxygen), changing glucose to ATP (it’s all about ATP!), ethanol, carbon dioxide, and water. This old, old, metabolic pathway dates back to the days before oxygen ruled our breath and is utilised by microbes. The hidden ones of the deep, single-celled, or living colonies, breathe through their single cell walls in ancient ways – acetogenesis, methanogenesis – to gain the blessed ATP.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Respiration (from spirare ‘breath’ and re ‘again’) is participation.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

And what is this creature that does not breathe (in or out) with no metabolism or need for ATP? This simple strand of genes in a designer jacket called a capsid? Does this thing, neither dead nor living, have a spirit? Like all living things was it breathed into life by the gods?

Or is this death-bringer undead? This assaulter of lungs? Lung-cell-killer and causer of coughs – dead lung cells coughed up as sputum, mucus, the yellow remains of what was ours?

By what dark programme does it turn the body against itself – alveoli ‘little cavities’ where the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen takes place filling with water – no space to make ATP? No lungs – no breath. The pump of ventilators, breathing in, breathing out, our new iron lungs…

Did it crawl from the cauldron of inspiration like the speechless dead or is it something entirely other?

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Respiration (from spirare ‘breath’ and re ‘again’) is participation.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

To whom do we pray? To the gods and goddesses of breath and to the spirits of inspiration? To Ceridwen, Gwyn ap Nudd, Morgana and her sisters, who gave us breath, and take it away?

“Breath always leads to me,” says Gwyn. I find this reassuring and disconcerting from a death-god. From the one who releases the spirits of Annwn from the cauldron and holds them back.

So we breathe together with the lunged and lungless creatures with skin, fur, feathers, shells, scales, leaves, hyphae, the single-celled, the uncelled who ride our breath, until we return to the gods. To the winds that carry the voices of all ancestors over our 4.543 billion year old earth.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Respiration (from spirare ‘breath’ and re ‘again’) is participation.

Inspire. Expire.

Anadlu i mewn. Anadlu i allan.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

*I adapted this meditation from an earlier version ‘The Ways We Breathe‘ previously published on Gods & Radicals following guidance from my deities to focus on my breath and being struck by the realisation that a distinguishing feature of coronavirus and other viruses is that they do not breathe.

Dormach and the Jaws of Annwn

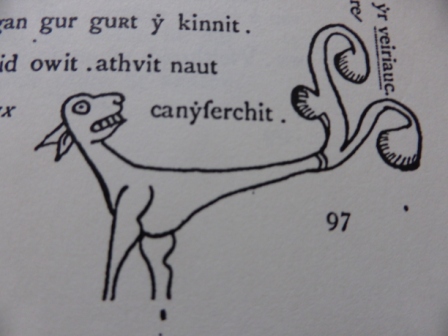

Dormach is the dog of Gwyn ap Nudd, who aids him hunting the souls of the dead. We have only one reference to Dormach by name in medieval Welsh literature. This is from ‘The Conversation Between Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ in The Black Book of Carmarthen (1350).

In this poem Gwyddno has died and is wandering the misty hinterlands between Thisworld and Annwn. There he meets with Gwyn, who offers him protection and slowly reveals his identity as a gatherer of souls. Gwyn introduces Dormach, then Gwyddno addresses the dog.

In Welsh this reads:

Ystec vy ki ac istrun.

Ac yssew. orev or cvn.

Dorma ch oet hunnv afv y Maelgun.

Dorma ch triunrut ba ssillit

Arnaw canissam giffredit.

Dy gruidir ar wibir winit.

Over the past two centuries this verse has been translated into English in various ways. The most recent and best translation is by Greg Hill (2015):

My hound is sleek and fair,

The best of hounds;

Dormach he is, who was with Maelgwn.

Dormach rednose – why stare you so?

Because I cannot comprehend

Your wanderings in the firmament.

Much controversy has surrounded the name, which is written twice as ‘Dorm ach’, with a letter erased. John Rhys assumed this was an ‘r’ giving ‘Dormarch’ with march meaning ‘horse’ ‘wholly inapplicable to a dog’.*

Rhys suggested ‘Dormach’ should instead be written as ‘Dormarth’, ‘a compound made up of dôr, ‘door,’ and marth.’ He went on to claim that marth is a ‘personification of death’ ‘of the same origin as the Latin mors, mortis… perhaps, the Marth which was the door of Annwn.’ Dormarth means ‘door-death’.

Rhys’s translation is now considered unconvincing. There is no evidence the letter was an ‘r’ and its erasure is viewed as a genuine correction. According to The Dictionary of Welsh Language, ‘Dormach’ means ‘burden, oppression’. There is textual evidence of its use from the 14th century until the 18th century. These meanings fit with medieval Christian conceptions of Gwyn and his dog(s).

Rhys notes that in Wales Bwlch Safan y Ci, ‘the Gap or Pass of the Dog’s Mouth’, is a metaphor for death and bears similarities with the English ‘jaws of death’ and German Rachen des Todes ‘jaws of death’. This argument for Dormach’s association with death and the door of Annwn seems sound. In the Brythonic and Germanic traditions we find corpse-dogs: Cwn Annwn (of whom Dormach is a member and perhaps their leader being ‘the best’) and Gabriel Ratchets, who hunt the souls of the dead and are viewed as death portents. To pass through the jaws of these dogs is to die and go to the next world.

In many world myths, dogs act as guardians to the lands of the dead. The most famous is Cerberus, who guards Hades in Greek mythology. He is variously depicted with one, two, three, or fifty(!) heads, one or more stinging serpent tails, and sometimes with a mane of snakes or snakes down his back.

Intriguingly, in The Black Book of Carmarthen, the scribe has sketched an image of Dormach with a dog’s head and near Cheshire cat-like grin, a dog’s forelegs, and a long body tapering to two serpent tails. He bears a striking similarity to Cerberus and may also have been viewed as a guardian of Annwn.

Part-dog, part-serpent, this image reminds me of the watery, subliminal imagery from the temple of Nodens/Nudd, Gwyn’s father. On a mosaic are two sea-serpents or icthyosaurs. On a mural crown Nodens is accompanied by icthyocentaurs with heads of men, front hooves of horses, and fish-tails.

Rhys notes by Dormach he is ‘reminded of the the medieval pictures of hell with the entrance thereinto represented as consisting of the open jaws of a monster mouth.’ He refers to the tenth century Anglo-Saxon Caedmon manuscript where the devil lies chained to a tooth and demons deliver sinners into the gaping maw.

Caedmon Manuscript

This shares similarities with the Urtecht Psalter (1055) from the Netherlands which features not only Hell Mouths but a ‘Hades Head’ (could we be looking at shared cultural representations of Pen Annwn, ‘Head of the Otherworld’?). The 11th century Anglo-Saxon Harley Psalter replaces the Hell Mouths with clefts, pits, vents, and chimneys leading into hollow hills where souls are tortured.

Utrecht Psalter with Hades Head

In these representations we find a mixture of pre-Christian Brythonic and Anglo-Saxon beliefs about the dead passing through the jaws of death to a world beneath the earth demonised and made hellish. Hell Mouths also appear on the left-hand side of Christ in the bottom corner surrounded by the demonic imagery of Hell (Heaven is on his right) in Doom paintings from across medieval Europe.

These depictions are clearly influenced by the Bible. In Isaiah 5:14 we find the lines: ‘Therefore Death expands its jaws, opening wide its mouth; into it will descend their nobles and masses with all their brawlers and revelers’ and in Numbers 16.32: ‘and the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them and their households, and all those associated with Korah, together with their possessions.’

In the Book of Jonah, Jonah was swallowed by a gigantic sea creature. In the Hebrew text it is called a dag gadol, ‘huge fish’, in the Greek ketos megas ‘huge fish’, a term associated with sea-monsters, and in the Latin ketos is translated as cetus ‘whale’. Jonah is described as being in ‘the belly of hell’, ‘cast into the deep’: ‘The waters compassed me about, even to the soul: the depth closed me round about, the weeds were wrapped about my head. I went down to the bottoms of the mountains; the earth with her bars was about me for ever.’ Jonah’s ‘soul fainted’, he offered up a prayer to God, and the whale vomited him up. Here we have a clear depiction of Jonah passing to and returning from another world. ‘Hell’ is translated from Sheol, the Hebrew name for the land of dead.

‘Jonah and the Whale’ by Pieter Lastman (1621)

In Matthew 12:40 Jesus compares his death, journey to Hell, and resurrection with the story of Jonah: ‘For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.’ The sea-monster’s belly and Hell are equated.

In ‘The First Address of Taliesin’, in The Book of Taliesin, the riddling bard poses the question:

Pwy vessur Uffern,

pwy tewet y llenn,

pwy llet y geneu,

pwy mein enneinheu?

What is the measure of Hell,

how thick is it veil,

how wide is its mouth,

how big are its baths?

Here ‘Hell’ is translated from Uffern, which derives from the Latin Inferno, and is used synonymously with Annwn. Margaret Hancock links the geneu ‘maw, jaws’ with the Hell Mouth and the ‘Hell monster’ in ‘The Battle of the Trees’: a ‘great-scaled beast’ with one hundred heads who carries fierce battalions ‘beneath the roof of his tongue’ and ‘in (each of) his napes.’ This beast, like the ‘black-forked toad’ and ‘speckled crested snake’ in whose flesh a hundred souls are tortured ‘on account of (their) sins’ is evidently a death-eater and it seems likely Dormach played a similar role.

These creatures appear to be native to the Brythonic pagan tradition and to Annwn. Whilst they appear monstrous to Christians, from a pagan standpoint, they might be seen as having an essential, albeit unpleasant, function in devouring the dead and acting as vehicles for their passage to the Otherworld.

Of course, such passages are not limited to the dead. As the journeys of Jonah, Jesus, and Taliesin show, the living can pass to Annwn and one of those ways is by entering the jaws of a devouring creature.

Is there some deep and universal truth in the image of the jaws of death? Are pursuit by a monstrous beast, being swallowed, devoured, spat out, integral to the journeys of our souls in life and in death? If this is the case should the ‘oppression’ of Dormach ultimately be seen as liberating, his ‘burden’ the key to release from our fear of death as we pass through his jaws to gain knowledge of the Otherworld?

*Rhys gives no argument for this and I disagree. The name of Arthur’s dog, ‘Cafall’, may derive from the the Latin for horse, Caballus, and mean he was as big as a horse. Bran, the dog of Gwyn’s Irish cognate, Finn, shared Dormach’s colouring with ‘two white sides’ and ‘a fresh crimson tail’ and his head was shoulder high. In the Irish myths we also find dog-headed figures with horse’s manes. There is therefore no good reason why Dormach should not be seen as horse-sized or even as horse-like.

SOURCES

Greg Hill, ‘The Conversation Between Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, Awen & Awenydd

J. Gwenogbryn Evans, The Black Book of Carmarthen, (Boughton Press, 2008)

John Rhys, Studies in the Arthurian Legend, (Adamant Media Corporation, 2001)

Marged Haycock, Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007)

Philip A. Bernhadt House, Werewolves, Magical Hounds, and Dog-Headed Men in Celtic Literature, (The Edwin Mellen Press, 2010)

Sarah Kemple. ‘Illustrations of damnation in late Anglo-Saxon manuscripts’, Anglo Saxon England, (2003)

Biblical quotes from Bible Hub

With thanks to Linda Sever for passing on Sarah Kemple’s illuminating article.