In Barddas Iolo Morganwg provides a mythical account of the origin of letters, which he claims was passed down from the ancient Bards of the Isle of Britain.

‘Einigain, Einigair, or Einiger, the Giant, was the first that made a letter to be a sign of the first vocalisation that ever was heard, namely, the Name of God. That is to say, God pronounced His Name, and with the word all the world and its appurtenances, and all the universe leaped together into existence and life, with the triumph of a song of joy. The same song was the first poem that was ever heard, and the sound of the song travelled as far as God and his existence are, and the way in which every other existence, springing into unity with Him, has travelled forever and ever… It was from the hearing, and from him who heard it, that sciences and knowledge and understanding and awen from God, were obtained. The symbol of God’s name from the beginning was /|\…

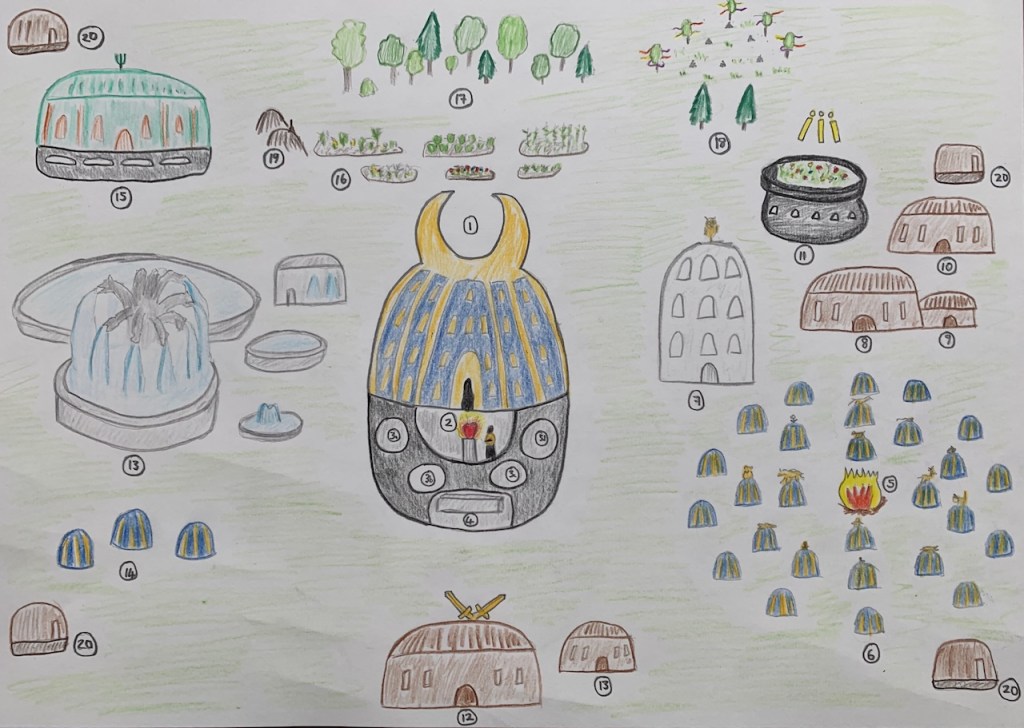

Einigan the Giant beheld the three pillars of light, having in them all demonstrable sciences that ever were, or ever will be. And he took three rods of the quicken tree, and placed on them the forms and signs of all sciences, so as to be remembered; and exhibited them. But those who saw them misunderstood, and falsely apprehended them, and taught illusive sciences, regarding the rods as a God, whereas they only bore His Name. When Einigan saw this, he was greatly annoyed, and in the intensity of his grief he broke the three rods, nor were others found that contained accurate sciences. He was so distressed on that account that from the intensity he burst asunder, and with his (parting) breath he prayed God that there should be accurate sciences among men in the flesh, and there should be a correct understanding of of the proper discernment thereof. And at the end of a year and a day, after the decease of Einigan, Menw, son of the Three Shouts, beheld three rods growing out of the mouth of Einigan, which exhibited the sciences of the Ten Letters, and the mode in which all the sciences of language and speech were arranged by them, and in language and speech all distinguishable sciences. He then took the rods and taught from them the sciences – all except the name of God, which he kept a secret, lest the Name should be falsely discerned; and hence arose the Secret of the Bards of the Isle of Britain.’

The letters were known as gogyrven, a term which has been translated as ‘spirit’ and ‘muse’, and provides the sense that the letters were inspirited and possessed their own lives and potent agency.

When etched onto wood with a knife each letter was known as a coelbren ‘omen stick’ and ‘The Coelbren’ was the name given to the alphabet, which later developed to contain twenty-four letters.

***

It has long been proven that Morganwg’s writings are forgeries and were not passed on from the ancient bards. They are also heavily influenced by Christianity. However, they may still be read as inspired works that contain deep truths open to reinterpretation from a modern Brythonic pagan perspective.

From numerous instances in medieval Welsh poetry where poets deny adamantly that awen is from God and not from the Great Goddess Ceridwen* we can derive that God replaced Ceridwen as the creator of the world and source of the awen. Their denials conceal an older truth. That the universe was born when she spoke her secret name which brought about the primal shattering of her crochan ‘cauldron’ or ‘womb’ – the Big Bang, and the echoing of her name throughout creation as awen-song.

If Ceridwen is our great creatrix, Old Mother Universe, who heard her song? Who is Einigan the Giant? A clue may be found in the name gogyrven or ogryven for letter. Ogryven is also the name of a giant. Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd speaks of ‘a girl in Ogyrven’s Hall’:

Unwilling to leave her (it would be my death)

My life-force is with her, my vitality ebbs

Like a legendary lover my desire undoes me

For a girl I can’t reach in Ogyrven’s Hall.

John Rhys says: ‘three muses had emerged from Giant Ogyrven’s cauldron. But Ogyrven seems to be one of the names of the terrene god, so that Ogyrven’s cauldron should be no other probably than that which we have found ascribed to the Head of Hades.’ It seems that Ogyrven is Pen Annwn, the Head of the Otherworld and guardian of Ceridwen’s cauldron. He is elsewhere known as Arawn or Gwyn ap Nudd.

The identity of Einigan with the Head of the Otherworld is consolidated by Iolo himself. In a later passage in Barddas, referring to the creation of the world we find the following dialogue:

Disciple: ‘By what instrumentality or agency did God make these things?’

Master: ‘By the voice of his mighty energy…’

Disciple: ‘Did any living being hear that melodious voice?’

Master: ‘Yes; and co-instantaneously with the voice were seen all sciences and all things cognitive, in the imperishable and endless stability of their existence and life. For the first that existed, and the first that lived, the first that obtained knowledge, and the first that knew it, was the first that practiced it. And the first sage was Huon, the son of Nudd, who is called Gwynn, the son of Nudd, and Enniged the Giant.’

Menw is a character from Welsh mythology who fittingly knows the language of the animals. The reference to him being the ‘son of Three Shouts’ may refer to the ritual cry of Diaspad Uwch Annwfn ‘the scream over Annwn’ and the power of the voice to summon Annuvian spirits to blight land and people.

Thus we have the seeds of an alternative story of the origin of letters inspired by Morganwg’s writings.

***

The Giant’s Letters

In the beginning there was Annwn, the Deep, a place of silent darkness within the crochan of the Great Goddess. In that silence, in that depth, a very small something formed – a name. And when the Goddess spoke her name, her womb, her cauldron shattered with an almighty bang, her waters broke and poured out in torrents of stars, planets, worlds, our beautiful world amongst them. The universe and its song were born from the secret name of Old Mother Universe and that song was known as awen.

But what is a song with noone to hear it? It was lucky that another of the gods of the Deep heard the song. He is known as Einigan the Giant, Ogryven the Giant, Gwyn ap Nudd, and countless other names. When he heard it, it was so powerful, so full of the joy of the becoming of the universe, so full of the sorrow of the shattering of the cauldron that would be never be whole again, that it seared three burning rays of light into his mind /|\. No matter whether he was sleeping or waking, no matter whether he sat still or ran or hunted through the universe for their source on his dark starry-eyed steed, they would not disappear and the song would not stop repeating itself over and over again.

“What is it you want? What is your demand?” he growled whilst resting at noon beneath a quicken tree.

“We want to be born, we want to be known, we want to be understood.”

The giant finally realised what must be done. Taking his knife he harvested a branch from the tree and cut it into three rods. Onto them he engraved markings for the ten deepest and most primal notes of the song, chanting each gogyrven over and over again, channeling into it its share of the light. When the three coelbren, ‘omen sticks’ as he called them, were formed, the rays faded from his mind. As he looked upon his creation he was filled with a feeling of deep satisfaction and peace and a strange but rightful emptiness, not unlike a mother who has just given birth to three beautiful children.

Yet he still could not rest until he found people who would come to know and understand his creation. He passed on the letters, but, to his horror, they soon lost their meaning. Rather than recognising them as the awen-song of Old Mother Universe, the echoing of her secret name, they began to worship the letters and the knowledge that they allowed them to accumulate instead. Every time a letter was written without purpose he was aware of the light of the universe fading out. He grew so angry that he broke the rods. The intensity of his grief burst his heart, burst him asunder like the broken cauldron. With his last breath he prayed their connection to the song of the awen and their rightful expression in poetry would be reclaimed.

A year and a day afterwards, Menw, son of Three Shouts, beheld the three rods growing from the giant’s mouth. Everywhere his parts had fallen the shoots of new forests of wild words sprang up. Menw learnt the letters and found to his delight they allowed him to commune with the animals who ran ran through those woodlands, with the stones, the rivers, the mountains, the bright shining stars. With all the things that echoed with the Song of Old Mother Universe. When he sang them out loud in perfect poetry he saw three rays of light burning in his mind and his heart was filled with joy.

Menw passed on the secrets of the awen to others who, like him, became awenyddion. When the last died, the light faded. Until those three rays were seen once again by an awenydd called Iolo Morganwg, who penned the story of Einigan the Giant. His works were passed on to others who would answer the giant’s prayer and reclaim the connection of his letters to the name of Old Mother Universe.

And what became of him? Death is rarely the end of a giant. Einigan died and returned to the cauldron. From it he was reborn as its guardian, the Head of Annwn, the ruler of the land of the dead from which the universe was born and to which it will return, as his reward for creating the letters.

*Taliesin says:

I entreat my Lord

that (I may) consider inspiration:

what brought forth (that) necessity

before Ceridfen

at the beginning, in the world

which was in need?

In ‘The Chair of Teyrnon’ we find tension between conflicting translations of peir as ‘cauldron’ or ‘Sovereign’ (God). ‘Ban pan doeth o peir / ogyrwen awen teir’; ‘Splendid (was it) when there emanated from the Sovereign/cauldron / the ogyrwen of triune inspiration’.

Amongst later bards petitioning Ceridwen for awen is only acceptable when disguised as a metaphor and under the ordinance of God. Cuhelyn Fardd asks God for poetic power akin to ‘the dignity of Ceridfen’s song, of varied inspiration’. Prydydd y Moch requests inspiration from God ‘as from Ceridfen’s cauldron’ and asks God for ‘the words of Ceridfen, the director of poetry’.

SOURCES

Greg Hill, ‘The Girl in Ogyrven’s Hall’, The Way of the Awenydd, (2015)

Greg Hill, ‘Who was Taliesin?’, Awen ac Awenydd

Iolo Morganwg, The Barddas, (Weiser, 2004)

John Michael Greer, The Coelbren Alphabet, (Llewellyn, 2017)

Kristoffer Hughes, From the Cauldron Born, (Llewellyn, 2013)

Marged Haycock (transl), Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007)

Sioned Davies (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007)