Category: Uncategorized

Building Polytheistic Monastic Practices Part Three – Trance

Trance refers to altered states of consciousness of varying degress between sleeping and waking in which a person becomes partially to fully unaware of their surroundings and might have experiences of spiritual realities.

States of trance include dazes, daydreams, reveries, raptures, ecstasies and soul flights. Trance can be voluntary or involuntary. It can be induced by a number of things including prayer, meditation, singing, dancing, rocking, repetitive music, fasting, thirsting, sweating, sensory deprivation and intoxicants.

In most religions trance is seen as less safe and accessible than prayer and meditation. In Christianity it is associated with the more advanced stages of prayer such as St Teresa’s Prayer of Union and with mystical experiences of God. Deep meditation, in Buddhism and Hinduism, is seen by some to be akin to or identical with trance, whereas others argue it is different because the person meditating remains mindful and present rather than unaware.

In indigenous cultures, whilst it is acknowledged that everyone can access trance states, there are respected spirit-workers who are specialists in carrying out spiritual work whilst in trance states for the benefits of their communities.

These trance states can be divided into two types. One is spirit flight, in which the spirit-worker’s soul leaves their body and they travel to the spirit realms in order to help other community members by finding lost soul parts, extracting negative entities, or negotiating with the Gods and spirits.

The other is trance possession, in which the spirit-worker calls the spirits into their body. This is sometimes for the purpose of healing. In other cases it can be so the spirits can speak with their people and offer guidance and prophecy. It can also simply be a gift for the spirits to be able to inhabit a body.

In the late 20th century Michael Harner and others developed core shamanism (from the term šaman ‘one who knows’ from the Evenki Tungus tribe in Sibera) from these practices by removing the rites, cosmologies and Deities associated with specific cultures and honing them down to their core.

In core shamanism the primary practice is the shamanic journey in which the practitioner travels to one or more of the three worlds (the Lower World, Middle World and Upper World) with the aid of a drumbeat at 180-250bpms to seek advice, guidance or healing for themselves or others from their spirit allies. The term ‘shamanism’ is now widely used to refer to any form of spirit-work.

*

Looking at archaeological and written records I have been unable to find any evidence for the practice of voluntary spirit flight in the Brythonic tradition. If our ancestors made drums or rattles as aids there is no evidence but this does not mean they didn’t exist as the organic materials might have rotted.

What we do find is evidence for voluntary trance possession. In his Description of Wales (1194) Gerald of Wales writes of ‘awenyddion, people inspired’, who ‘when consulted upon any doubtful event’ ‘roar out violently’ ‘rendered outside themselves’ ‘possessed by a spirit’. Their answers are ‘nugatory, ‘incoherent’ and ‘ornamented’ (this description is suggestive of the symbolic, metaphorical and often poetic language of myth and the Otherworld). When ‘roused from their ecstasy, as from a deep sleep’ they remember nothing and when questioned again they give different answers. ‘Perhaps they speak by the means of fanatic and ignorant spirits.’

In medieval Welsh literature we find references to ‘witches’ such as the witches of Caer Loyw, Orddu and Orwen, who are killed by Arthur and his warriors likely because they held powerful positions as warriors and spirit-workers.

We also find the stories of people who become wyllt ‘mad’ or ‘wild’ as part of an initiatory process that leads to them becoming people inspired. The most famous example is Lailoken / Myrddin Wyllt. Traumatised by fighting in the Battle of Arfderydd he sees warriors in the sky and an endurable brightness then is torn out of himself by a spirit and assigned to the Forest of Celyddon. For thirty years he wanders ‘with madness and madmen’ before he heals and becomes a poet and prophet who warns about future wars.

The notion of a period of madness preceding becoming a spirit-worker is found throughout cultures and is now commonly referred to as ‘shaman sickness.’

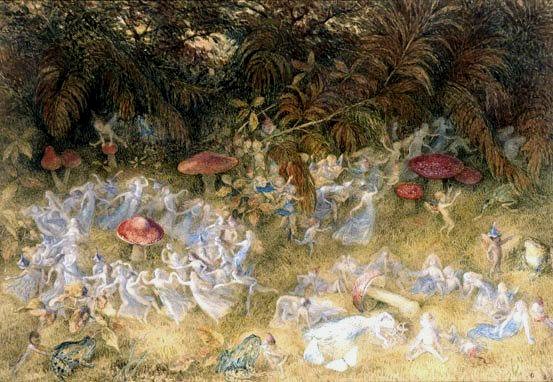

In Welsh folklore we find countless stories about people being transported to the land of the fairies by music, dancing, or seduction. It’s not clear whether some of these involuntary travels are in spirit or in body. Those who go in body face dire consequences for time passes differently in Faerie. It seems they’ve only been away a moment yet when they return a hundred or more years have passed, they are no longer recognised, or crumble to dust. These tales warn us that it is a bad idea to travel to the Otherworld in a physical form.

*

In my late teens and early twenties I had experiences of trance leading to visions of the spirit realms when I was going to festivals and night clubs and dancing all night on various concotions of intoxicants. What surprised me was that I was the only one having visionary experiences whilst my friends just reported having a good time, which led me to fear I was going mad.

I went through a long period of mental health problems (anxiety, panic attacks, depression, over and under-eating, self-harm, suicidal ideation and dependence on alcohol) which I only starting getting over when I met my patron God, Gwyn ap Nudd, discovered my visions were of Annwn / Faery, our British Otherworld and I had been seeing His people, the ‘fairies’, and began serving Him, firstly as an awenydd, more recently as a nun of Annwn.

Whether this was a form of ‘shaman sickness’ or was mainly down to my struggles as an autistic person in a neurotypical world remains in question without the knowledge of the elders of a spiritual community to help with my discernment. It’s my personal opinion that it was a little bit of both.

I was first introduced to shamanic practices by attending workshops with a local Heathen, seidr man Runic John, but found I didn’t connect strongly enough with the Norse Gods and cosmology. I also tried core shamanism with Paul Francis but struggled with the psychotherapeutic approach.

I didn’t dare journey alone until Gwyn came into my life and offered to take me to the Otherworld. Without a drumbeat or any other method of inducing trance I just went and I’ve been able to journey whenever I’ve felt the call of Gwyn and my guides or with a few preparatory prayers and songs ever since.

Although I’ve experienced being possessed by the awen and by Gods and spirits when I’ve been writing I’ve only recently started practicing trance possession. One of my practices focuses on the Speaking Ones, seven crow spirits who I invite to come into my body to lend me their voices for oracles. I’ve also recently experienced inviting my spirits into my body during ecstatic dance in a shamanic workshop and am planning to take this practice further.

Since 2013 I’ve been attending shamanic journey circles in core shamanism with the Way of the Buzzard firstly in person then since Covid online. I like Jason and Nicola’s approach because it is well grounded in the landscape of Britain and in the natural history of our land and its plants and animals.

In response to instructions from Gwyn I’ve just started training as a shamanic practitioner with the Sacred Trust. Progressing from journeying for personal guidance and inspiration to healing others is a big step for me but I see it to be a neglected part of my calling I have fled from, resisted, for far too long.

*

In conclusion to this series I’ll finish by saying for me, as an awenydd and nun of Annwn, as a spirit-worker in the Brythonic tradition, and as an aspiring shamanic healer, prayer and meditation form the bedrock of my practices.

Without them, without regular prayers and offerings to my Gods, without grounding myself through meditation, breathwork, body postures and other embodiment practices I wouldn’t have the foundations to practice trance safely enough to extend my services to healing other people.

It’s been a long difficult journey with few way markers along the way. But I’m here now, doing what I’m here to do, and I hope by sharing my writings I will make it a little easier for others who are called to this hard yet sacred work.

Return to King of Annwn Cycle and new Patreon tiers

I guess it was always going to happen. I couldn’t set it down for long. When I gave up my desire to be a professional author at the end of last year I let my King of Annwn Cycle series of books go with it. Since then I’ve felt like a part of me is missing and when I’ve been praying and meditating with Gwyn I’ve felt a yearning to have a full story of His life to meditate on and been filled with sadness at its absence. I’ve also had a niggling feeling that my promise to write ‘His book’ in my failed version was unfulfilled.

This feeling has grown and grown. Over the past couple of days I have found myself looking back at the old material and thinking in the earlier poetry and story fragments from the beginning and the poem from the end I still have something. It’s not going to be a fantasy-style novel to sell in the mainstream or an epic re-imagining of a Brythonic creation myth but a story of Gwyn’s birth and creation of His kingdom which might appeal to other Gwyn devotees and to followers of this blog.

When I asked Gwyn if He wanted me to return to it He said “Yes – it’s my gift.”

In these simple words I perceived a delightful reciprocity. It’s my gift from Him to gift back to Him. A gift from us to those who are open to receiving it. This reciprocal process of gifting forms the core of my devotional relationship with Gwyn and with my audience.

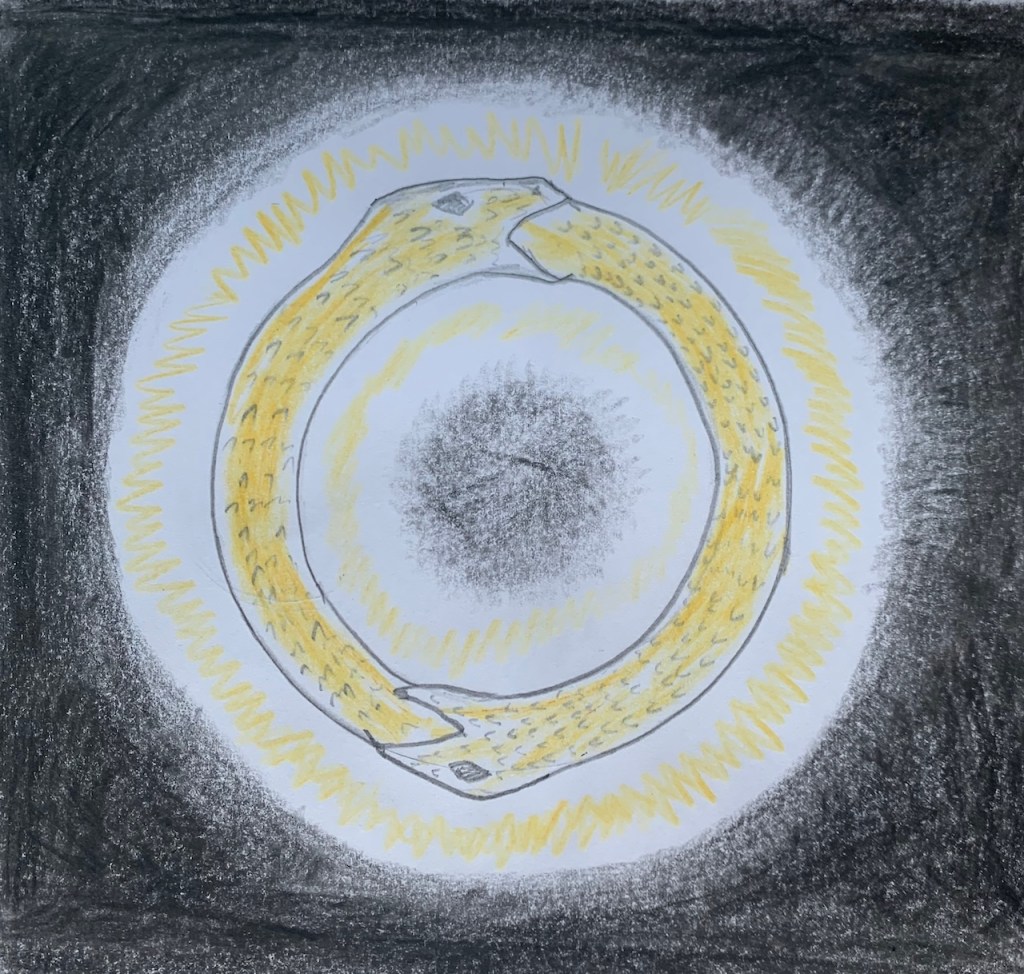

Gwyn also gave me a symbol to represent the King of Annwn Cycle – His golden ring with two serpents biting one another’s tails. This double ouroboros has meaning for me on many levels. Driving the cosmic cycle are the battles between the red and white serpents, between Gwyn and Gwythyr, and this also represents how patron and devotee, the Gods and humanity, feed upon and nourish one another.

In response to this and to other inspirations I have updated my Patreon tiers to reflect that I am able to give more and thus perhaps to ask for a little more in return.

~

£1 Fairy Ring

You will have access to a quarterly patron only online Q & A session and discussion on Annuvian / Faerie lore and exploring Annwn and building relationships with its Gods and spirits.

£2.50 News from Sister Patience

You will receive the aforementioned and my quarterly newsletter on the equinoxes and solstices in which I will share news about my life as a polytheist nun through the seasons.

£4 Visions from the Mist

You will receive the aforementioned and fortnightly patron only posts where I will share visions and experiences from journeys and spirit work which I will not be sharing in public.

£7 King of Annwn Cycle Excerpts

You will receive the aforementioned and monthly patron only excerpts from my King of Annwn Cycle.

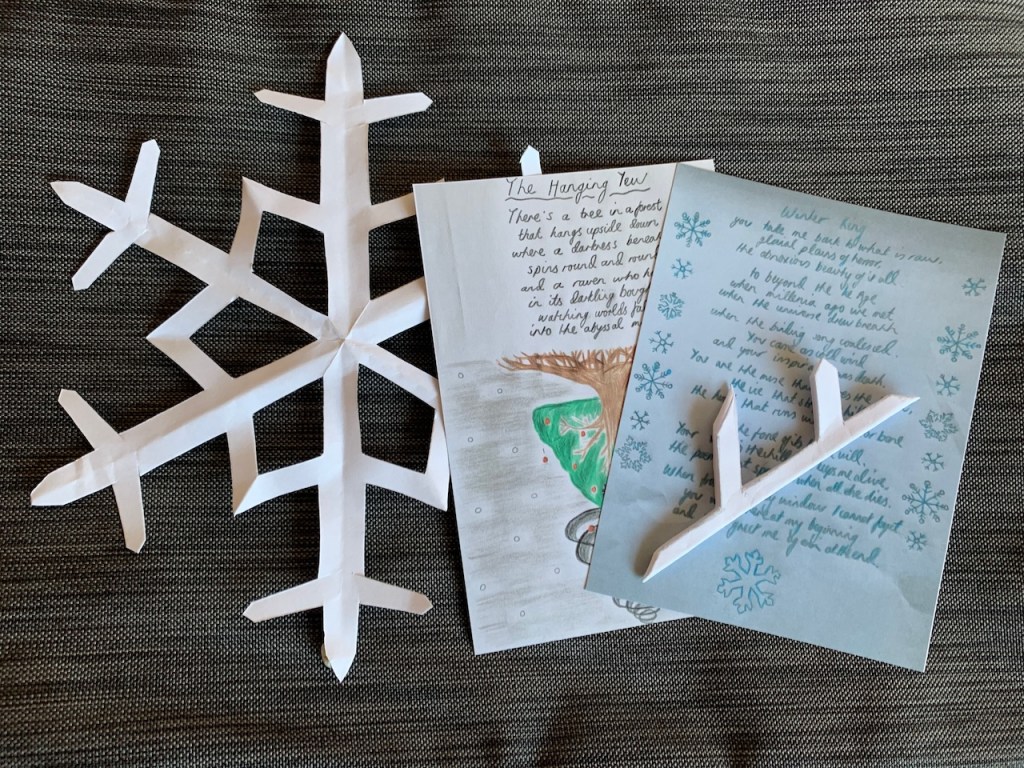

£10 Winter Gifts

You will receive the aforementioned and winter gifts in the post at the Winter Solstice which will include illustrated poetry, drawings, and print outs of my best work.

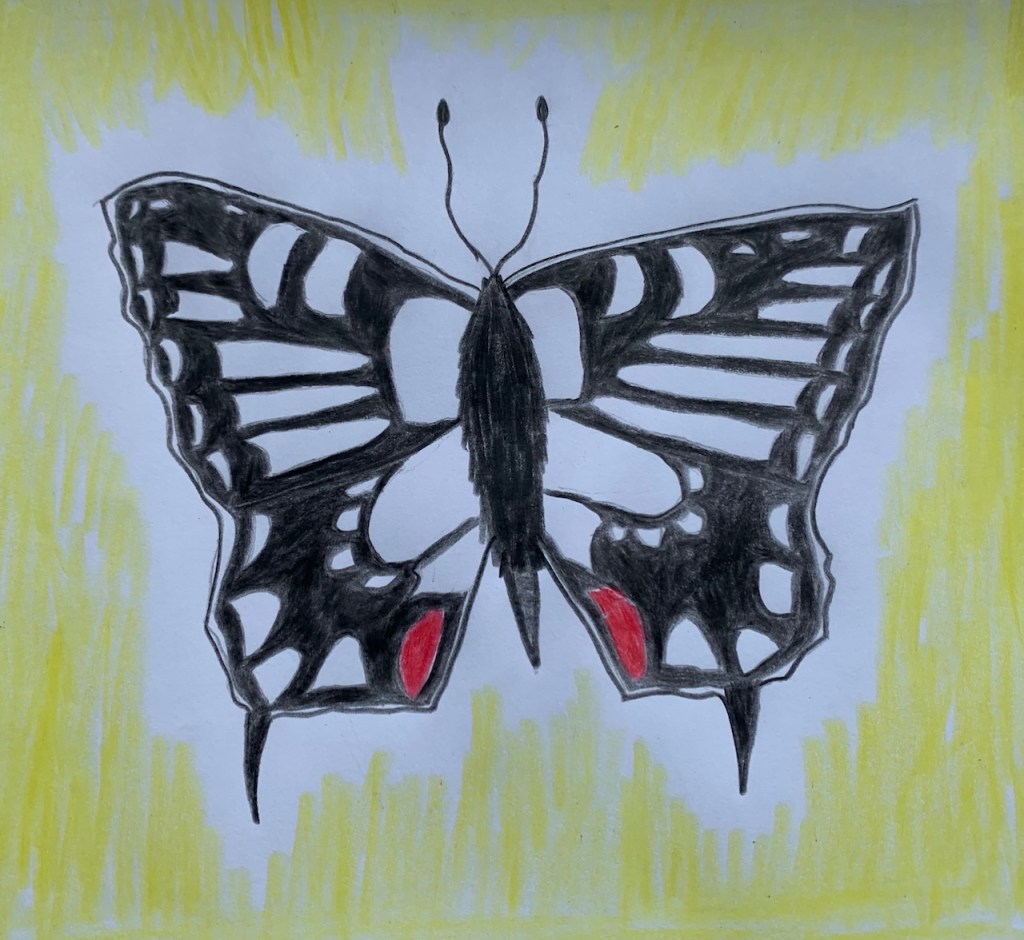

£12 Annuvian Butterflies

You will receive the aforementioned and up to four 30 minute soul guidance sessions per year which can include divination and explorations of Annwn, its Deities, and the lore.

£15 Mythic Books

You will receive the aforementioned, free PDFs of my existing books on joining, your name in my future books and free print and digital copies when they are published.

You can join my Patreon HERE.

Contemplating the Abyss Part Two – Writing whilst Falling

I write when I fall. It’s a defence mechanism. Like putting out a hand to catch myself.

I write because writing has saved me and I believe my writing might help others.

But putting out a hand doesn’t always work when one is falling into the Abyss…

*

I cried out to the philosophers, “Philosophers save me!”

When I was 21 and in the second year of my philosophy degree I sat on the edge of the Abyss at the nadir of a quasi-initiatory period during which I’d been foolishly been mixing phenomenology (1) with copious amounts of drugs and alcohol, some unknown part of me striving, reaching for… what?

My ‘friends’ had deserted me because I’d ‘gone west’ and I was sitting on the boot of a car, at the end of the world, staring into the Abyss, feeling I couldn’t go on living but not really, truly, wanting to die either. I couldn’t choose.

I was presented with three gateways but didn’t have the courage to take any.

I moved into the front seat of the car and, as dawn arrived, pinking the front windows of my friend’s house, with it came three alienesque beings who I now understand in the Brythonic tradition to be ellyllon ‘elves’. They took me into the heavens in what I saw at the time as an alien aduction experience and performed an intricate operation on my brain with silver instruments.

After that I decided to give up drugs entirely and apply myself to my studies. Not easy. There were after effects. Anxiety. Panic attacks. I ended up on medication but also got subscribed what I really needed – exercise. These things helped me to get my head straight enough to write myself out of the Abyss.

My philosophy studies gave me the tools I needed. I saw my inability to choose life or death as akin to Kant’s antimonies (2) which stem from the use of reason to comprehend sensible phenomena beyond its application. I wrote my dissertation on the concept of the sublime in Burke, Kant, and Lyotard, focusing on how experiences of the sublime depose the rational mind (3).

This helped me to understand the breakdown of my rational faculties but not the visions I encountered as the flip side. It was only when I was studying for my MA in European Philosophy and writing my dissertation on Nietzche’s The Birth of Tragedy I found the clues. Dionysian ecstasy gives way to Apollonian visions. But I wasn’t seeing Dionysus or satyrs. I realised, like Greece, Britain, must have its Gods and spirits, finally met my patron God, Gwyn ap Nudd, a King of Annwn, realised my visions had been of His realm.

Nietzsche, a philosopher, who also stared into the Abyss (4), saved me.

*

The medieval Welsh term Annwn stems from an ‘very’ and dwfn ‘deep’. I believe it shares similarities with the Hebrew term tehom which means ‘deep’ and was translated as abyssos, ‘abyss’, ‘bottomless depth’, in the Septugaint, the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible in 285–247 BCE.

The Mesopotamian Goddess of the primordial waters, Tiamat, has been linked to tehom. Several years ago myself and other awenyddion found a Goddess named Anrhuna who takes dragon form and is the mother of Gwyn. She plays a similar role as the personification of Annwn. In my visions She, Gwyn, and Nodens/Nudd are associated with the Abyss and its mysteries.

Gwyn was the God who taught me how to fall. He’s fallen too. And I’ve fallen with Him. I’ve crawled out of the Abyss with Him, claw by claw, word by word.

That damned book. It came first when I was falling during the first covid pandemic. I’d given up my supermarket job to volunteer my way into paid work in conservation and my volunteering had been cancelled leaving me with no paid or voluntary role. Utterly unpublishable but writing it got me through.

It came again when I realised I couldn’t cope in a career in the environmental sector. For the last year and a half I’ve worked on it full time, realised it is no good.

That crutch has gone but I’m still putting my hand out – writing whilst falling.

*

I’m back in another antinomy – I love writing but can’t make a living from it.

When I first met Gwyn He asked me to promise to give up my ambition to be a professional author in return for journeying with Him to Annwn. I did it for a while. I took various jobs, cleaning, packing, supermarket, wrote as service for my Gods.

But, sneakily, oh so sneakily, in the back of my mind, I never got rid of the treacherous hope that promise would only be temporary. If I worked hard well enough the veto might come off, I might be able to have my cake and eat it.

I published three books. Sold more copies than I hoped for such niche work. Even got professionally published. Not enough to make a living of course but enough to convince me I might be able to write something that did better.

Ten years after my initial dedication to Gwyn I asked Him by divination about whether that promise still holds and got 1. The Wanderer and thought I was free of it. It’s notable here I asked through the tarot rather than asking Him directly. Consciously I did this because I feared my discernment might be off. Maybe unconsciously, I feared, knew, he’d say, ‘No’. I read the card wrong. In the traditional tarot The Wanderer is the The Fool. I was fooling myself. As I write these words I hear the laughter of my God and realise what a fool I was.

At one point I hoped In the Deep might not only sell to my small Polytheist and Pagan audience but might also appeal to fantasy readers, taking the stories of Gwyn and the other Brythonic Gods into the mainstream.

Hubris. It didn’t work. An individual can’t write myth. And I’m not that good a writer.

A difficult lesson learnt. My ambition to be a professional writer given up for good, vomited up, committed to the Abyss, I’m falling again, writing whilst falling.

I’m remembering my vision of the three gates. I can’t make a living as a writer. I don’t want to die either. I’m asking what lies beyond the third gate.

In the next part I will be writing about the ‘Abyss Mystics’ who, unlike me did not try to cling on, to write themselves out of the Abyss, were not afraid of falling.

(1) In particular using Husserl’s epoche (setting aside all assumptions of existence) as an experiential practice.

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kant’s_antinomies

(3) In ‘Scapeland’ Lyotard writes of the ‘The Thing’ as sublime – ‘the mind draws itself up when it draws a landscape, but that landscape has already drawn its forces up against the mind, and that in drawing them up, it has broken and deposed the mind (as one deposes a sovereign), made it vomit itself up towards the nothingness of being-there.’

(4) In Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche wrote, ‘Battle not with monsters lest ye become a monster; and if you gaze into the abyss the abyss gazes into you.’

In Service to Creiddylad

So, to You,

finally I turn, still

not knowing truly

who You are,

remembering

how, twenty years ago,

my philosophy tutor criticised me

for prioritising the sublime over the beautiful.

Yes- the sublime is Him – the power within and beyond

the land, in Annwn, in the cold mountains, the ice of the Ice Age,

all that threatens to tear the body, the mind, the soul apart,

yet, like Rilke’s angels, disdains entirely to destroy us.

And yes – the beautiful is You – the power who arrives

after the winter, after the Ice Age, You who brought the flowering plants

after your mother brought the mosses many aeons ago.

After being torn apart You are the one who heals after the awe,

after the awful, after near-death, the out-breath of the Awen – Life.

I have always avoided the beautiful, drawn instead to the darkness

where beauty cannot be seen because it is too painful.

That’s why You come veiled to Your suitors in Your white dress,

why only He can undress You, fully understands you…

To them You are always riding away on Your white winged horse.

In their longing they do not see the gifts of the flowers

You leave in your steps, Your beauty unveiled in every hoof print.

They long only to tame You, yoke You, at the mounting block.

I shall not be like them, seeking to master You, possess You,

instead I shall come with reverence for Your veil, Your veiled ones,

with a patience for every flower, not forcing them to reveal their secrets.

I, who have served Death, will learn to put Life beside Him as a Goddess.

It was a long, long time ago when I was criticised for prioritising the sublime over the beautiful. It has always stuck with me. I avoided our modern conception of beauty because it is so confused, so tainted, by the glossy photographs we see in magazines.

In the Welsh myths Creiddylad is described as ‘the most magnanimous maiden in the Islands of Britain’. She is generous, forgiving, She is the sister of Gwyn ap Nudd, King of Annwn, and His beloved. He is Otherness, She is Hereness, She is Presence, She is what we might call mindfulness today amongst the flowers.

I spent seven years with Him and now I am called to walk with Her in my new role as an ecologist.

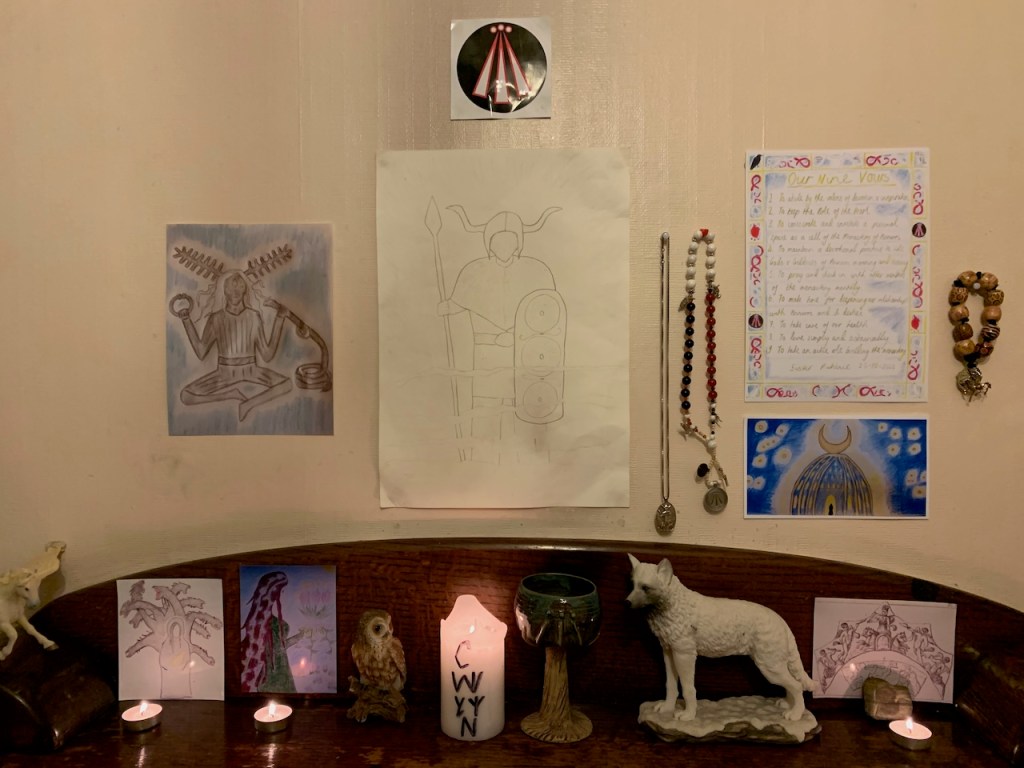

My rearrangement of my altar reflects these changes as I give Gwyn and Creiddylad equal space. The plant is, oddly, a Bromeliad, from the tropical Americas, which I sensed She liked when I did our weekly food shopping at Morrisons. It represents the fact that neither plants nor gods know any boundaries.

A Glimpse of Pure Sunshine

The final prose poem in Melissa Lee-Houghton’s challenging confessional collection, Sunshine, is called ‘Hope’. Hope is scarce. The subject is a dream akin to a horror movie where the narrator is kidnapped and her companions are beheaded one by one, ‘blood gushing like red schnapps.’ When she is the only one left alive for a moment she thinks she’s won. Yet the time arrives for her to hang her head over the metal sink for the man in the white surgeon’s mask with the scalpel. ‘Hope’ ends with the following lines: ‘Although my psychiatric worker said it’s more than unusual, I died in that dream, and I went somewhere. Part of me remains there, happily, in the glamorous glare of lost hope and a sadness spun of pure sunshine.’

This poem struck a chord because two years ago I had a horrific dream ending with the suggestion of an afterlife. I was a soldier fighting in a jungle and had been captured to be executed. As I faced the firing squad, I knew I was going to die. I called to Gwyn ap Nudd, my patron god, for help. Filled with superhuman strength, I broke away in the form of a heavily muscled pig-like warrior. However, I was tracked down and recaptured. When I consulted Gwyn from my cell, he told me he couldn’t save me again. I must send my soul into the hazel, the beetle and… a third thing I can’t remember when it came to my execution. The next minute I was walking amongst hazel trees with a friend, speaking with complete calm about how to get my soul into a tree and turning over the leaves to find a beetle. I was utterly convinced about the survival of my soul, the calmest and surest I’ve ever felt. That reassuring feeling, like a glimpse of pure sunshine, remains with me to this day.

Gwyn’s Feast

For 29th of September an introduction to Gwyn’s feast, its abolition, and how it can be reclaimed. ‘Join us by holding a feast for Gwyn, performing a ritual, making an offering, reading a poem, raising a glass, or simply speaking his name.’

Gwyn ap Nudd is a god of the dead and ruler of Annwn. As the Brythonic leader of ‘the Wild Hunt’ he gathers the souls of the deceased back to his realm to be united in an otherworldly feast. This repast of the dead can, at certain times of the year, be participated in by the living.

Unfortunately this is a tradition that Christians went to great lengths to bring to an end. This article will introduce the evidence for Gwyn’s Feast, how it was abolished, and how it might be reclaimed by modern polytheists.

*

In ‘The Spoils of Annwn’, as Pen Annwn, ‘Head of the Underworld’, Gwyn presides over a feast in Caer Vedwit, ‘The Mead-Feast Fort’. At its centre is the cauldron of Pen Annwn, with its ‘dark trim, and pearls’, which ‘does not boil a coward’s food’: a vessel symbolic of rebirth.

Arthur raids seven…

View original post 1,410 more words

Lamentation for Catraeth

‘By fighting they made women widows,

Many a mother with her tear on her eyelid’

Y Gododdin

After Catraeth battle flags sway in the wind.

Storm darks our hair. Our tears are rain.

We press cheeks against cold skin,

load biers with sons and husbands

who will never drink in the mead-hall again,

lift weapons, smile across a furrowed field,

mend the plough, yoke oxen, share a meal,

touch ought but blood-stained soil,

chilled fingers reticent to let go.

Storm sky breaks. Our love pours out.

Ravens descend on soft wings to take them.

How we wish they would take our burning eyes,

flesh we rend with nails unkempt

from the year they left for Din Eiddyn,

drunk their reward before it was earned

at dawn with sharpened spears

at daybreak with clashing spears

at noon with bloody spears

at dusk with broken spears

at night with fallen spears,

shattered shields, smashed armour, severed heads.

Seven days of wading through blood.

Of each three hundred only one lives.

Their steel was dark-blue. Now it is red.

Because of mead and battle-madness

our husbands and sons are dead.

We rend our veils. The veil is rent.

We long to tear out our hearts

and offer them instead

to the Gatherer of Souls approaching

with the ravens and hounds of death,

whose face is black as our lament,

whose hair is the death-wind,

whose touch is sorrow,

whose heart is the portal to the otherworld.

Our men rise up to meet him.

The march of the dead is his heart-beat.

The dead of centuries march through him.

The great night is his saddle.

The dead men ride his horse.

Forefathers and foremothers hold out their hands.

We do not want to let go but they slip

through our fingers like water

like tears

from sooty eyelids

into the eyes of others

into the eyes of their kin

to gather in the eyes of the Gatherer of Souls.

They are stars in our eyes now.

They are stars in the eyes of the hounds of death,

marching from drunken Catraeth:

the battle that knows no end.

Dogs of Carlisle

I went to Carlisle looking for proof of the claim it was the capital of Rheged and thus the seat of Urien Rheged where Taliesin sang his praises. I was also curious about whether I’d find any traces of Gwyn ap Nudd in the context of my research into his forgotten connections with the Old North.

I didn’t find what I expected and I found many things I didn’t expect. Such is the way of the world when you venerate a god of strange dogs…

*

Carlisle Cathedral

When I got to the entrance of the grounds of Carlisle cathedral I was stopped dead in my tracks by a stunning black-backed gull with a blush of red on his yellow beak, red star-studded rims around yellow eyes and black tail feathers spotted white. It wasn’t just his colouring. I felt like I recognised him.

However, there was a man eating a burger on the bench beside me. It wasn’t a time for talking to gulls. I looked around the ruins of the chapter house, the fratry, the friar’s tower, and St Cuthbert’s church then approached the doors of the cathedral.

On either side were sculptures of dogs. One was thickset, heavy-jowled, mouth open as if to speak an order or breathe out a blast of wind. The other was smaller, crouched, leaner, ready to pounce with an intriguing serpent-like fork at the end of her tail. Guard dogs. They let me pass.

Inside were chapels to St Wilfrid and St Michael, statues of bishops sleeping like corpses on their tombs. In the treasury a beautiful Roman glass bowl, stones engraved with early Christian art, collections of chalices, platens, jewellery. I was most impressed by the high star-studded ceiling and the ornate artwork on the misericords.

Misericord means ‘mercy seat’. The monks stood for their seven daily sets of prayers hence their seats folded down. However for the elderly and infirm a small shelf was created for support. This is the origin of some wonderful art: wyverns, man-headed lions, a siren with a mirror, a woman beating a man, St Margaret of Antioch being swallowed by a dragon and eaten by a boar*. In a world where neither prayer nor craftsmanship are valued, the time and effort put into carvings to support the backsides of praying monks seem undreamable.

There was no mention anywhere of Urien Rheged or Taliesin. When I got out, the gull was waiting at the entrance. I sat on the wall and shared some crumbs from my sandwich. An old woman approached, remarked on the proximity of my ‘friend’ and told me there had not been black-backed gulls in the area until a pair nested on one of the roofs. Everyone was terrified the little grey chicks would tumble out. Yet they’re alive and well and it looks like they’re staying.

*

Carlisle Castle

Like the Cathedral, Carlisle Castle was built (in stone) in the early 12th century but was founded on an earlier site. This was known in the Romano-British period as Luguvalium ‘Strong in Lugus’ and as the capital of Civitas Carvetiorum: the territory of the Carvetii tribe (‘the deer people’). A Roman fort which housed 1000 men was built there in 73AD then another called Petriana facing it on the north bank of the Eden.

Due to its powerful defensive position near the confluence of the rivers Eden and Caldew and to Hadrian’s Wall plus its earlier status as a tribal centre (which may have become one of Nennius’ 26 cities: Cair Ligualid) scholars have conjectured it may have been the capital of Rheged.

I walked the walls, descended into the half-moon crescent, found the well, and the tower where Mary Queen of Scots had been kept. Descending into the basement of the keep, once a storehouse and dungeon, I read how the thirsty prisoners had been forced to lick the stones for moisture.

In that inner cell I spotted grooves in the stone, a wet glint. Water? I touched it and my finger came away damp. Like a tongue. I felt the crush of bodies, the walls closing in, said a quick prayer for those who had been imprisoned, and rushed back to the light.

On the first floor the Great Hall with its expansive fireplace was the kind of place you could imagine a poet performing for a King. However, once again neither Urien nor Taliesin were mentioned. Up another flight of stairs a pair of walls decorated by bored 14th C guards with drawings from coats of arms and oral tales. Engraved on the door: a huntsman and his dogs.

*

The Eden and Caldew

I walked from the castle down to the river Eden, noting the path that runs along the line of Hadrian’s Wall. The Eden would have felt peaceful if it wasn’t for policemen searching for something in snorkels which set me slightly on edge. At the spot where the Eden and Caldew meet I touched the water and saw a shoal of tiny newly hatched fish.

Up the Caldew jackdaws flocked between the trees. As I walked back through the woods I felt like I was surrounded by them every way I turned: a fairytale moment, a jackdaw on every branch, in every ear. I don’t see jackdaws in Penwortham and was enchanted by their roguish presence. At the end of the wood I found a freshly fallen feather.

*

Curse and Counter

Walking through the subway between the castle and city centre I came across the infamous Cursing Stone. Designed by Gordon Young and made by Andy Altman it was set in place in 2001. It is inscribed with the Curse of Carlisle, which was used against the Border Reivers by the Archbishop of Glasgow in 1525. The curse is 1069 words long. It begins:

“I curse their head and all the hairs of their head; I curse their face, their brain (innermost thoughts), their mouth, their nose, their tongue, their teeth, their forehead, their shoulders, their breast, their heart, their stomach, their back, their womb, their arms, their leggs, their hands, their feet and every part of their body, from the top of their head to the soles of their feet, before and behind, within and without.”

The Cursing Stone has caused controversy because since its instalment Carlisle has suffered from a spate of bad luck including foot-and-mouth disease, floods, rising crime and unemployment and the relegation from the league of Carlise United football team.

Christians have campaigned to have it removed. I noticed behind the stone was a door engraved with a Christian prayer and a cross saying ‘blessing’: an attempt to redress the negativity of the curse? Ensuingly someone less high-minded had written beside ‘honourable’ ‘just’ ‘pure’ in permanent marker, ‘Ha ha your God is dead.’

*

Tullie House Museum

You could spend days in the Tullie House Museum learning about the history of Carlisle (from a hand-axe dating to 10,000BC to the modern-day) and looking at the art-work. I had only a couple of hours left so had to keep my focus on finding something relating to Urien and Taliesin.

The bottom floor was entirely dedicated to Roman Britain and included statues and altars to the Roman deities and interactive spaces where you could enter a tent or try on jewellery. I noticed a brooch featuring a hunting dog then upstairs a dog statuette from the Romano-British period. Both put me in mind of the votive hounds offered to Gwyn’s father, Nudd/Nodens.

To my surprise I found numerous sculptures of Celtic deities: a Celtic wheel-god (Taranis?), three sets of Genii Cucullati, three sculptures of the Mother Goddesses and a dedication, a Celtic horned god, the eye-catching ram-horned head from Netherby with his deep, sunken eyes and fathomless expression. There were also altars to Hueteris, Belatucadrus, and Mars Cocidius.

I’d seen many sketched in Anne Ross’s Pagan Celtic Britain and wasn’t prepared to see them all together at once. It was overwhelming and rather peculiar seeing them packed into four cabinets; some headless, limbless, or defaced. I managed to get my act together and speak their names, those I knew, those I didn’t. Images of deities sculptured 2,000 years ago, revered, now viewed in a entirely different context.

The most surprising find was a cauldron. I’ve been researching the stories of the broken cauldron in British mythology for the past two years yet this was the first time I’d seen a cauldron in real life. The Bewcastle Cauldron was found during peat cutting at Black Moss, was missing its handles and coincidentally had been repaired five times by patching. Most astonishingly it was surrounded by orange lights; in ritual, I place candles around my cauldron in the same manner! Once again there was no sign of Urien or Taliesin.

*

A Wild Dog Chase

If I’d seen a goose I might have been able to say I’d been on a wild goose chase. However, I found myself led along my journey by a variety of strange dogs, birds (but no geese), and other bizarre creatures to the cabinet of the gods and the ‘grail’ itself: the handle-less patchwork cauldron.

A strange day out and in the non-logic of it this ‘wild dog chase’ I sense the presence of my Annuvian deity…

*I found out the correct identities of the carvings on the misericords from an obscure pamphlet called Cry Pure, Cry Pagan by Thirlie Grundy which a friend coincidentally happened to own.