In the previous post I looked at abyss mysticism in the writing of medieval monastics. Here I shall discuss how it relates to the visions of the Abyss that formed the core of my attempted novel, In the Deep, and to my own experiences.

The Christian abyss mystics of the medieval period perceived the soul and God to be dual abysses. Through a process of annihilation, led by love, the abyss of the soul was dissolved in the abyss of God. Van Ruusbroec conceived this slightly differently suggesting the Abyss was a ‘God beyond God’.

The process of annihilation was one that involved suffering. Penitence, purgation, purification, to varying degrees in different authors but the result was ultimately joyous union with God as the ‘divine’ or ‘blessed’ abyss.

The big difference between my own experiences and visions and those of these Christian mystics is theological as I am a polytheist and not a monotheist and find it difficult to identify the Abyss with the Christian God.

The Abyss has a presence in my life as something powerful, as something divine, as a deity, but not as a God I can name. Thus Van Ruusbroec’s conception of it as a ‘God beyond God’ resonates deeply with me as does the positing by the Gnostics of a God of the Deep preceding the creator God whose prior existence is suggested in Genesis 1.2 ‘And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.’ The terms ‘deep’ and ‘abyss’ stem from the Hebrew tehom and are often used interchangeably.

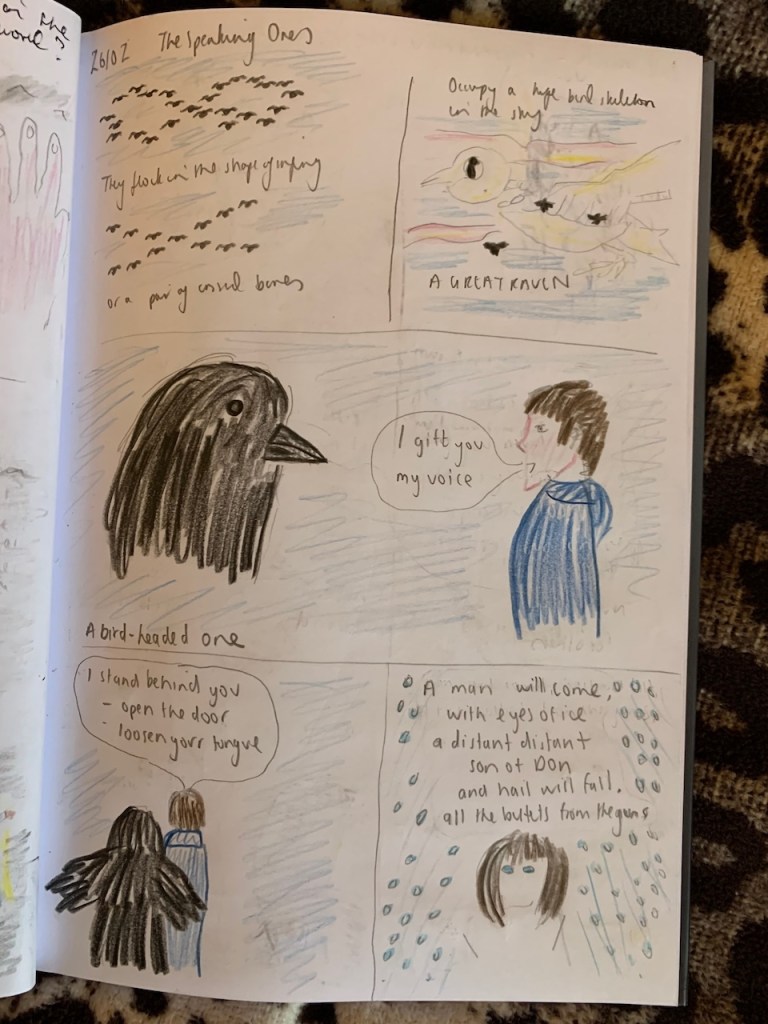

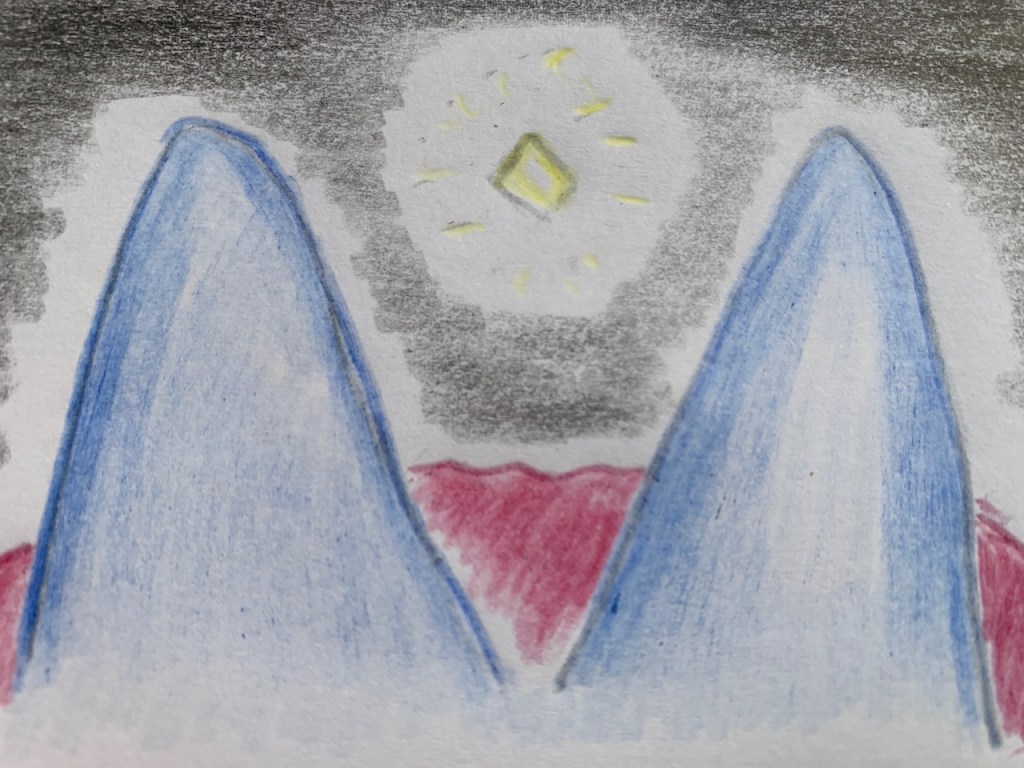

In the cosmology that has been revealed to me by the Brythonic Godsthe Abyss is part of Annwn, ‘Very Deep’, its deepest part, its bottomless depth. It is a place to where the souls of the dead return and from it are reborn.

The way I envisage it bears remarkable similarities to the vision of Hadewijch of Antwerp – ‘an unfathomable depth’, ‘a very deep whirlpool, wide and exceedingly dark; in this abyss all beings were included, crowded together and compressed’.

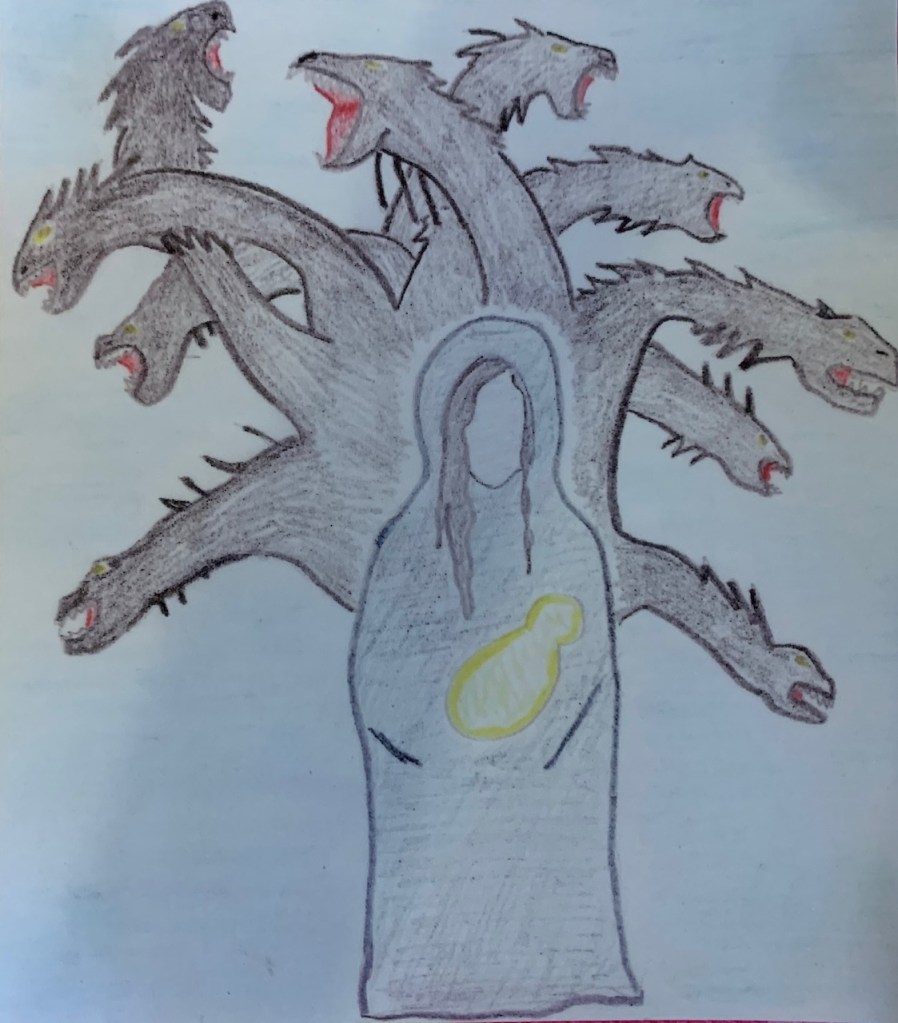

It is associated with deep wisdom that can only be won as a result of sacrifice. In the stories I was shown Nodens / Nudd agreed to give up His sword arm. He hung over the Abyss in the coils of the Dragon Mother, Anrhuna, the Goddess of the Deep, and received the knowledge, ‘There is no up or down or before or after – everything meets here in you the Dragon Mother.’

Vindos / Gwyn ap Nudd hung over the Abyss on a yew wounded in raven form and gave every last drop of his blood in exchange for a vision ‘to set the world to rights’. His knowledge was brought out of Him by a series of riddles and He saw Himself as a black dragon before plummeting dead into the Abyss.

At the beginning of the next book in death He was united with ‘the source’:

Vindos fell,

and as he fell he left behind

his shell of bones and black feathers

and his soul flew free on wider wings

on the winds of the Abyss.

He had won

their favour

through his offering

of every last drop of his blood.

By his wounding, by his questioning,

agony had become ecstasy.

The bottomless

abyss

was no longer bottomless.

He had mastered its paradoxes and knew

where darkness turns to light

and death to life.

Down was

now up

and he was one

with the source, the spring

from which the ocean of the stars

sprung when the universe

was born.’

These scenes bear similarities with Marguerite Porete’s words about the soul, in annihilation, finding ‘there is neither beginning, middle nor end, but only an abyssal abyss without bottom’ before acheiving ecstatic union with God.

It seems my Gods, Nodens / Nudd and His son, Vindos / Gwyn are presenting to me a tradition of sacrifice to the Abyss in return for its wisdom. By leading the way they are showing what might be expected of Their devotees.

My first experience of the Abyss took place as the result of an unconscious process of self-annihilation – dissolution of the self through the combination of practicing Husserl’s epoche (putting all one’s presuppositions about the nature of reality aside) with drugs and alchohol and all night dancing.

There was a yearning within me, I might now say deep for deep, abyss for abyss, but I didn’t know what it was and when I got to the Abyss it terrified me. I wasn’t ready for abyssal wisdom. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t understand its choices, to live as I was or to die physically, or to take a third door.

I see in my own impulses and those of the abyss mystics, love and annihilation, the interplay of eros the ‘life drive’ and thanatos the ‘death drive’ which together lead to the Abyss and to union with the divine if one is prepared to surrender to make some sacrifice of themselves.

I’ve never been good at giving or sacrifice always wanting things my own way.

Ten years ago, Gwyn, my patron God, a King of Annwn, asked me for a sacrifice in exchange for the wisdom of Annwn – to give up my desire to be a professional author. I did so… but not in full… I secretly entertained a hope if I gave it up for a period I might be let off and be able to have my cake and eat it.

My experience of writing In the Deep, spending a year and a half on a novel that has turned out unpublishable and daring to think it might sell more widely than my previous publications has shown this is not the case.

It’s taken me ten years to realise I must give up my biggest dream in full for good.

This fits with the process of self annihilation found in the medieval mystics. Only by giving up our desires, surrendering our will, can we walk the path of the Gods and with them find a deeper unison with the God beyond the Gods.

I believe this also relates to the need to give up my identity as Lorna Smithers, published author, performing poet, public speaker, to become Sister Patience.

In the Deep was not written purely for self gain. First and foremost it was written for love** of Gwyn, as an origin story for Him, as an offering. I believe it is because of that the awen flowed and I retain these visions as His gift.

That He, ‘White, Blessed’, has led me to the blessed Abyss, the God beyond the Gods, who may or may not be the formlessness of the Mother of the Deep before She took form.

To the third door – to die to his present life, to be annihilated, hopefully like Vindos / Gwyn to be reborn.

He was

the first microbe

and every single tiny thing.

He was an ammonite and a starfish,

He was a silver salmon,

every fish.

He swam

amongst bright creatures

as an eel, as a seasnake, as a snake,

as a horned serpent, as a bull, as a wolf.

Playful as a new-born pup

Vindos

chased his tail

and the trails of starships

and traversed every wormhole

before he emerged from the sea of stars

and climbed out of the cauldron,

naked, dripping, triumphant,

and very much living

to stand beside Old Mother Universe.

*I also wrote the sequel, The Spirits of Annwn, in draft form as a long poem, when possessed by the awen last year.

**Unlike annihilation love is a difficult thing for me to talk about as someone who, after a number of botched relationships, only discovered they were asexual and aromantic late in life. Unlike a number of Gwyn devotees with an intense devotional relationship with Him I am not a God spouse. Much inside me rebels against using the language of marriage found in Christianity such as ‘bride of Christ’ and even ‘love’ with its sexual and romantic connotations in reference to our relationship. I wish there was a word for purely devotional love.

In part five I will be writing about how these insights relate to the Brythonic tradition.