‘He becomes intent to roll out the entire splendour of the Universe that is contained in His heart…’

~ Swami Maheshwarananda

When I first started practicing yoga in 2022 in the hope it would help with my hip and knee problems I had no idea that I would fall in love not only with the asana ‘postures’ but with pranayama ‘breathwork’ and dhayana ‘meditation’. I never guessed that I would find such astonishing parallels between the Hindu God Shiva, ‘Lord of Yoga’, and my patron God, Gwyn ap Nudd, who presented Himself to me as our Brythonic ‘Master of Meditation’. Both, I realised, come from a shared Indo-European origin.

I found similarities exist between Shiva and Gwyn on a symbolic level. Both are associated with bulls and serpents and with intuitive insight and visionary experience. Shiva’s often seen as a destroyer and Gwyn has destructive potency as a leader of the Wild Hunt and the God who holds back the fury of the ‘devils’ of Annwn in order to prevent their destruction of the world.

There’s a story about Shiva riding down the mountain to His wedding feast on a huge bull ‘covered in snakes and ash’ ‘with ghosts and demons’ ‘some had their mouths in their stomachs, some had only one foot and some had three’. Yet when He and His company ‘crossed the wedding portals’ and entered the presence of His bride, Shakti, they were transfigured into ‘a handsome young man’ and ‘divine beings’ (1). This spoke immediately to me of the paradoxical nature of Gwyn and the spirits of Annwn who are referred to both as furious ‘devils’ and as beautiful and beneficent fair folk.

Whilst studying yogic meditation in more depth with the Mandala Yoga Ashram I discovered an incredible text called the Vigyana Bhairava Tantra from the Kasmir Shaivite tradition.The ashram founder, Swami Nischalanda, refers to it as his Bible and many of the practices within the ashram derive from it. Over recent months I have taken a short course (2) and read Swamiji’s exposition of it in Insight Into Reality from which I gleaned many insights.

Bhairava ‘Fearsome’ or ‘Awe-Inspiring’ is another name for Shiva which evokes qualities of Gwyn, whilst vigyana means ‘insight’ and tantra ‘techniques’. The text is also known as Shiva Vigyana Upanishad ‘The Secret Teachings of Shiva’. Within, Bhairava addresses His consort, Bhairavi as His Beloved and student, teaching Her in 112 dharanas ‘concentrations / lessons’ how to gain insights into the fundamental nature of reality. As I’ve been listening to and practicing the dharanas I have felt that Gwyn is speaking through it to me as His student and beloved as a nun of Annwn.

In The Edge of Infinity Swami Nischalananda provides an account of the history of Kashmir Shaivism. He says: ‘In the past, tantra was widely known as Shaivism, ‘the Path of Evoking Shiva’, a system of mysticism rooted in indigenous shamanism. It existed throughout India well before 1500 CE, the start of the vedic period’ (3). Tantra, as an oral tradition, predates the Vedic texts, with its first scriptures emerging in the first millenium CE. Kashmir Shaivism originated in 850 CE with one of the main texts being the Shiva Sutras which were gifted to Vasugupta by Shiva in a dream. The Vigyana Bhairava Tantra is central and was written down around 7 – 800CE.

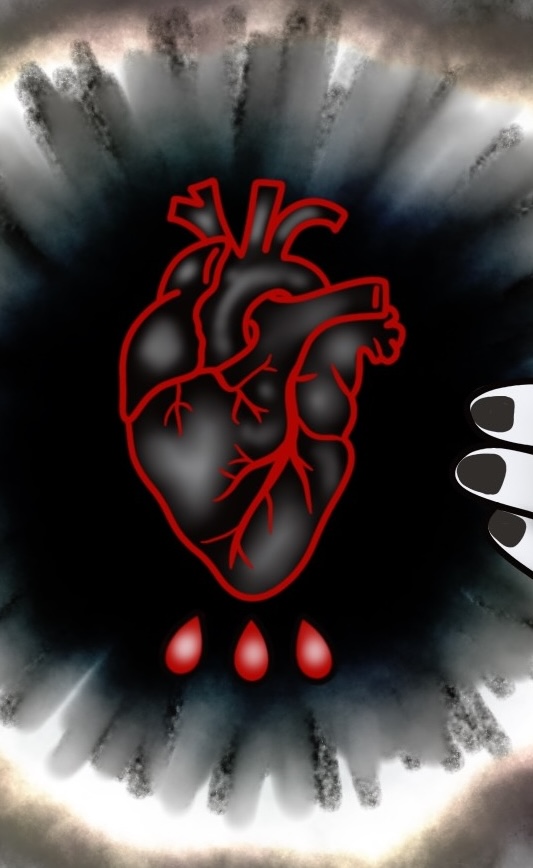

I was incredibly excited to find out that a number of texts, such as Pratyabhijna Hridayam ‘The Heart of Recognition’ and The Triadic Heart of Shiva, refer to the universe unfolding from Shiva’s heart and to His residence in the heart.

‘When He becomes intent to roll out the entire splendour of the Universe that is contained in His heart… he is designated as Sakti.’ (4)

‘The Heart, says Abhinavagupta, is the very Self of Siva, of Bhairava, and of the Devi, the Goddess who is inseparable from Siva. Indeed, the Heart is the site of their union (yamala), of their embrace (samghata). This abode is pure consciousness (caitanya) as well as unlimited bliss (ananda)… The Heart, says Abhinavagupta, is the sacred fire-pit of Bhairava. The Heart is the Ultimate (anuttara) which is both utterly transcendent to (visvottirna) and yet totally immanent in (visvamaya) all created things. It is the ultimate essence (sãra). Thus, the Heart embodies the paradoxical nature of Siva and is therefore a place of astonishment (camatkara), sheer wonder (vismaya), and ineffable mystery. The Heart is the fullness and unboundedness of Siva (purnata), the plenum of being that overflows continuously into manifestation. At the same time, it is also an inconceivable emptiness (sunyatisunya). The Heart is the unbounded and universal Self (purnahantä).’ (5)

‘He, truly, indeed, is the Self (atman) within the heart, very subtle, kindled like fire, assuming all forms. This whole world is his food. On Him creatures here are woven. He is the Self, which is free from evil, ageless, deathless, sorrowless, free from uncertainty, free from fetters, whose conception is real, whose desire is real. He is the Supreme Lord. He is the ruler of beings. He is the protector of beings. This Soul, assuredly, indeed, is Isana, Sambhu, Bhava, Rudra.’ (6) (The names at the end are all epithets of Shiva).

Reading these words was meaningful for me because Gwyn revealed to me that His heart is the Heart of Annwn ‘Very Deep’ (the Brythonic Otherworld). During my practice of playing the heartbeat of Annwn on my drum for an hour every week I have experienced visions of the universe and its people being born from Annwn like red blood pouring from His heart and returning at death like blue blood. When we entered a sacred marriage He came to dwell within my heart as ‘the Heart of my Heart’. I was told that my heart is also the Heart of Annwn and the universe unrolls from my heart (which fits with the practices emphasising the importance of the heart-space in yoga).

As I read more about Kashmir Shaivism I found further similarities with the cosmology I have been gifted in visions from Gwyn. In Kashmir Shaivism the fundamental ground of reality is Brahman or Parama ‘Ultimate’ Shiva. In mythology it is represented as the serpent-king Nagaraja ‘the infinite… who spreads out the universe with thousands of hooded heads, set with blazing, effulgent jewels’ (7). Before I had read these lines I was shown that the ground of reality is Anrhuna, the Mother of Annwn, the Dragon Mother, who has nine dragon heads with jewels in their foreheads and an infinite number of coils.

In a vision I was shown how Anrhuna was slaughtered and Gwyn and His sister, Creiddylad, were torn from Her womb. Through eating His mother’s heart Gwyn inherited the Heart of Annwn and became King of Annwn (8). Creiddylad brought life to the world as the energy behind creation – the ‘green fuse’ of vegetative life and by breathing life into living creatures.

This bears a resemblance with Kashmir Shaivism wherein Brahman divides into Shiva (Consciousness) and Shakti (energy and matter). There are parallels between the Heart of Annwn being the source of the universe from which all living beings are born and to which they return and the Heart of Shiva being the source of all energy and matter manifesting as Shakti.

Intriguingly, the first three dharanas in the Vigyana Bhairava Tantra focus on the origin and end points of the breath. When I practice these exercises I find myself contemplating how Creiddylad gave breath to life and Gwyn takes it away.

Finding these similarities between Kashmir Shaivism and the Annuvian monasticism I am developing for Gwyn has been revealing and exciting. I’m sure there is much more to be discovered as I continue with my research and practices.

REFERENCES

(1) Swami Nischalananda, Insight into Reality, (Kindle Edition, 2019), p393

(2) https://www.mandalayogaashram.com/self-study-course-vigyana-bhairava-tantra

(3) Swami Nischalananda, Insight into Reality, (Kindle Edition, 2019), p387

(4) Jaideva Singh, Pratyabhijna Hridayam, (Sundar Lal Jain, 1963), p30

(5) Paul Eduardo Muller-Ortega, The Triadic Heart of Siva, (State University of New York Press), p71

(6) Ibid. p82

(7) Richard Freeman, The Mirror of Yoga: Awakening the Intelligence of Body and Mind, (Kindle Edition, 2019) p19

(8) This story has a basis in medieval Welsh mythology. In Culhwch and Olwen, Gwyn kills a king called Nwython then feeds his heart to his son. I believe this might evidence an earlier ‘Cult of the Heart’ that preceded the ‘Cult of the Head’ wherein the soul was seen to dwell in the heart and the wisdom of one’s ancestors could be passed on by eating their hearts.