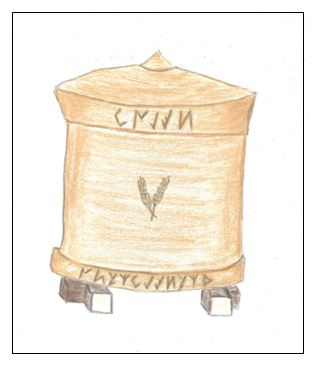

‘The Vat and Dish of Rhygenydd the Cleric: whatever food might be wished for in them, it would be found.’

Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain

It’s a secret knowledge

passed down by generations:

the perfection of malt, mash, wort,

the duration of fermentation,

the best flavouring herbs.

Rhygenydd kept the doors

of his brewery shut – the people

of the North imagined him winnowing,

threshing, malting, sparging, boiling,

praying as he added yeast

and closed the lid of the vat.

They wondered if he knelt palms

pressed together in prayer to God

or petitioned pagan grain gods,

for the Vat of Rhygenydd

brewed Britain’s finest food.

Little did they know with one wish

the cleric could summon any ale:

pale, light, malty, dark, bitter

with bog myrtle or sweetened

with heather or meadowsweet,

that behind closed doors he liked

to sample each tipple and could

be found snoring contentedly,

an empty tankard in his hand.

To which monastery did he pass on

his secret and who owns the vat now?

I’m doing a round of the breweries,

comparing pales, IPAs, stouts,

amassing my tasting notes…

~

If I was a cleric

with a magical dish

would I take it round

the cities of the North:

Liverpool, Manchester,

York, Carlisle, Newcastle,

Glasgow, Edinburgh,

in each square wish up

bread, fruit, stew, soup,

feed all the homeless

or keep it locked up

in a gold-adorned box

opened only on Sundays

and offer one thin wafer

to melt on each tongue?

~

Rhygenydd Ysgolhaig ‘the Cleric’ does not appear by that name in any other sources. Rachel Bromwich notes the resemblance of the name to Renchidus episocpus who with Elbobdus episcoporum sanctissmus (Saint Elfoddw) gave Nennius the information about the baptism of Edwin of Deira by Rhun ap Urien, which appears in The History of the Britons.

Nennius notes Edwin seized the kingdom of Elmet from Ceretic (son of Gwallog) and a year later received baptism by Rhun along with twelve thousand of his subjects within forty days. This took place in York in 627. By this time Rheged had been integrated into Northumbria. It seems Rhun maintained a position of power as a bishop. As Rendichus gives such importance to Rhun baptising Edwin it is possible he was connected with former Rheged and supported the taking of Elmet from Ceretic, whose father, Gwallog had turned against Urien and his sons.

Vat is translated from gren, ‘big vat or vessel, tub, pail, pitcher’. I found this somewhat confusing in relation to its property of generating ‘food’ until I realised that, well into the medieval period, ale was seen as a food-like source of nourishment and the vat was likely used for brewing.

People have been brewing in Britain since grain has been cultivated. In Skara Brae on Orkney, Neolithic buildings were found with a malting floor, kiln flue, pots for mashing, and huge Grooved Ware pots with stone lids for fermentation that contained 30 gallons. ‘Vats’ of this nature have been found near a number of Neolithic henges and stone circles demonstrating the longevity of our tradition of drinking at seasonal rituals.

Although wine was imported into Britain in the Roman period, it was mainly drunk by the ruling classes. Soldiers and non-Romans, particularly the Britons, drank ale. Wine was consumed less in the North because of the difficulties transporting it. One of the tablets from Vindolanda is inscribed with a request to ‘order beer’ for the soldiers and our earliest reference to a brewer: Atrecus cervesarious, is from the Roman town.

When the Roman Empire collapsed it was the monasteries who retained the knowledge of brewing and wine-making. This fits perfectly with Rhygenydd the Cleric owning a magical vat.

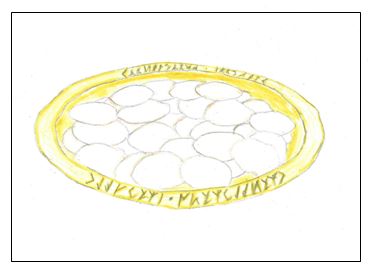

It’s difficult to pinpoint when people began eating from wooden plates or dishes because wood rots. One of the earliest examples in Britain comes from the Bronze Age settlement at Must Farm where ‘a number of wooden platters… carved from a single piece of wood’ were preserved due to a fire.

Although people began hand-making pots from clay by the open fire method during the Neolithic period we do not find any earthenware plates. Wheel-made Samian tableware along with silver and pewter dishes were imported by the Romans. One of the best known dishes is the Great Dish, which was made of silver, weighed 8 kilograms, and was decorated with the face of Neptune and other Roman deities including Bacchus, Pan, Silenus, maenads, and nymphs.

Was Rhygenydd’s dish of similar make and proportions, perhaps minus the pagan deities, or was it humbler? Within the Christian tradition bread is served on a ‘paten’, a small plate, usually made of silver or gold’ as part of the mystery of the Eucharist alongside wine.

~

SOURCES

Kenneth Jackson, ‘On the Northern British Section in Nennius,’ Celt and Saxon: Studies in the Early British Border, (Cambridge University Press, 1964)

Michelle of Heavenfield, ‘PW Rhun ap Urien of Rheged, Heavenfield

Merryn Dineley and Graham Dineley, ‘From Grain to Ale: Skara Bra, a Case Study’, Neolithic Orkney in its European Context, (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000)

Robin Wood, ‘History of the Wooden Plate’

Rupert Millar, ‘Send beer! The Romans in North Britain’, The Drinks Business

‘Alcohol in the Middle Ages, Dark Ages, or Medieval Period’, Alcohol Problems and Solutions

‘Dig Diary 25: Wooden Objects’, Must Farm

‘Gren’, Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru

‘Paten’, Wikipedia

‘Mildenhall Treasure’, Wikipedia