Nodens ‘the Catcher’ was worshipped across Britain in the Romano-British period. This is evidenced by his temple at Lydney, an inscription at Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall, and two silver statuettes found in Lancashire on Cockerham Moss suggesting the existence of a nearby shrine.

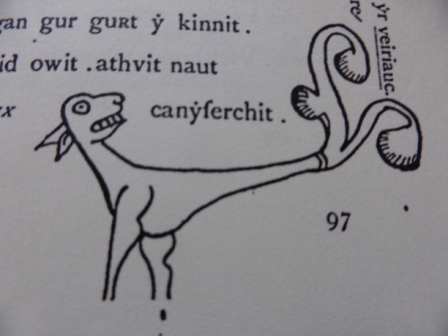

In medieval Welsh literature Nodens appears as Lludd Llaw Eraint. Lludd originates from Nudd ‘Mist’ and ‘Llaw Eraint’ means ‘Silver Hand’. A bronze arm found in Nodens’ temple in Lydney supports this link. His iconography and identifications with Mars and Neptune suggest he was a sovereignty figure associated with hunting, fishing, war, mining, healing, water, weather, and dreams. Many of these skills would have depended on his catching hand, which was lost and replaced in silver. Sadly we have no Brythonic stories explaining how Nodens/Nudd/Lludd got his silver hand.

Therefore we must turn to the Irish myths and the story of Nodens’ cognate Nuada Airgetlám ‘Silver Hand’ in The Battle of Moytura. This opens with the Children of Nemed departing from Ireland to escape the oppression of the Formorians, their exile in Greece, and return to Ireland to reclaim their land as the Fir Bolg at the time ‘the children of Israel were leaving Egypt’ (around 1000BCE*).

The Lebor Gabála Érenn informs us that the Children of Nemed split into three groups – the Fir Bolg, one that went to Britain, and one that went North and became the Tuatha Dé Dannan. It is amongst the Tuatha Dé Dannan, ‘People of the Goddess Danu’, that we find Nuada as High King.

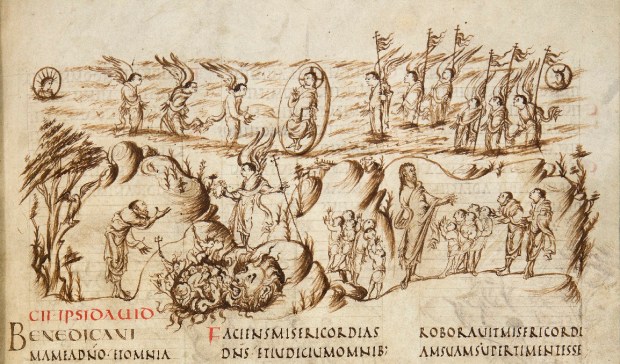

In The Battle of Moytura we are told the Tuatha Dé Dannan returned to Ireland from the North to reclaim their share of the land from the Fir Bolg ‘in a cloud of mist and a magic shower’. Nuada made the demand: ‘They must surrender the half of Ireland, and we shall divide the land between us.’

The Fir Bolg refused and this led to a fearsome battle. Nuada played a central role. He ‘was in centre of the fight’ with ‘his princes’, ‘supporting warriors’ and ‘bodyguard’ and took on Sreng, the Fir Bolg’s champion. Sreng ‘struck nine blows on the shield of the High-King Nuada, and Nuada dealt him nine wounds.’ During this combat Nuada lost his hand, which is described dramatically in vivid detail. ‘Sreng dealt a blow with his sword at Nuada, and, cutting away the rim of his shield, severed his right arm at the shoulder; and the king’s arm with a third of his shield fell to the ground.’

Nuada was carried from the battlefield. This is followed by a striking and grotesque scene: ‘His hand was raised in the king’s stead on the fold of valour, a fold of stones surrounding the king, and on it the blood of Nuada’s hand trickled.’ What to make of this? I’ve heard of severed heads put on stakes and revered due to the belief the soul resides in the head, but not of severed limbs raised on folds of stones. Perhaps this represents a tradition where a ruler or warrior’s strength was believed to reside in his sword arm/hand. For this reason the hand/arm received reverence whilst its mutilated owner was seen as lacking in strength (this would explain Nuada’s later demotion).

Afterwards the Tuatha Dé Dannan gained ascendancy. A truce was called and the Fir Bolg were given three options: to leave Ireland, share the land, or continue fighting. Sreng decided to fight and challenged Nuada to single combat. ‘Nuada faced him bravely and boldly as if he had been whole.“If single combat on fair terms be what you seek, fasten your right hand, as I have lost mine; only so can our combat be fair.” This shows Nuada was seen as unwhole yet still acted bravely and fairly.

Sreng refused. Taking counsel, the Tuatha Dé Dannan decided to offer Sreng ‘his choice of the provinces of Ireland’. ‘A compact of peace, goodwill, and friendship’ was made and Sreng chose Connacht.

Because he was not whole Nuada was forced to step down from his position as High King. He was replaced by the half-Formorian half-Dannan prince Bres. Bres oppressed the Tuatha Dé Dannan: ‘their knives were not greased by him… their breaths did not smell of ale; and they did not see their poets nor their bards… nor did they see their warriors proving their skill at arms before the king.’ Ogma was forced to carry fire-wood and the great father-god, the Dagda, served as a rampart-builder.

During this period a silver hand was made for Nuada through the combined efforts of the physician, Dian Cecht, and the brazier, Credne. It seems both an intimate knowledge of human anatomy and skill at silver-work were required for this process. Successfully crafted, it ‘moved as well as any other hand’. This scene is uncannily reminiscent of modern bionic technologies.

What follows is even more uncanny. Credne’s son, Miach, felt an inexplicable disliking for Nuada’s silver hand. We are told ‘he went to the hand’ (here, frustratingly it is not clear if he is speaking to the severed hand or to the silver hand) ‘and said “joint to joint of it, and sinew to sinew”; and he healed it in nine days and nights. The first three days he carried it against his side, and it became covered with skin. The second three days he carried it against his chest. The third three days he would cast white wisps of black bulrushes after they had been blackened in a fire.’

Here we find a complex ritual for the regeneration of a flesh-and-blood hand! Again, this seems to predict modern stem cell research; scientists are still struggling with complex processes of decellurisation and recellurisation in order to grow ‘ghost limbs’. Another example of a regenerating hand from the Welsh myths is the monstrous appendage that snatched Pryderi and Teyrnon’s foal and was chopped off by Teyrnon no doubt to reappear the next Calan Mai for more victims.

Similar miraculous healings took place in The Battle of Moytura. Both the Fir Bolg and the Tuatha Dé Dannan dug Wells of Healing. The Fir Bolg’s physicians ‘brought healing herbs with them, and crushed and scattered them on the surface of the water in the well, so that the precious healing waters became thick and green. Their wounded were put into the well, and immediately came out whole.’

The Tuatha Dé Dannan’s well was called Slaine. Dian Cecht and his sons Octriul and Miach chanted spells over it ‘to kindle the warriors who were wounded there so that they were more fiery the next day.’ It not only healed the wounded, but the mortally wounded and brought the dead back to life! ‘They would cast their mortally-wounded men into it as they were struck down; and they were alive when they came out.’ It shares qualities with the Cauldron of Regeneration in the Welsh myths.

Returning to the narrative, Bres was deposed. Nuada, with his flesh-and-blood sword hand, now whole, and thus seen as capable of rulership, was returned to his position of High King, now ruler of Ireland. Bres journeyed to the lands of his Formorian father and raised an army, led by Balor of the Piercing Eye.

As they approached, ‘making a single bridge of ships from the Hebrides to Ireland’, ‘terrifying’, ‘dreadful’, ‘a handsome well-built young warrior wearing a king’s diadem’ arrived at the gates of Nuada’s court. Cue the entry of Lug Lormansclech, ‘the son of Cian son of Dian Cecht and of Ethne Daughter of Balor’. Lug was half Danann and half Formorian. ‘Lormanslech’ means ‘Long-Handed’. It was revealed the youth is Samildanach, ‘many-skilled’. Like Nuada, many of his talents, such as building, smithing, fighting, playing a harp, were dependant on his sword-hand.

Nuada welcomed Lug and, perceiving his superior skill in combat, surrendered his kingship to him on the condition he released the Tuatha Dé Dannan from the oppression of the Formori. In the following battle Nuada was defeated and killed by Balor. Lug avenged Nuada by slaughtering Balor, his grandfather, by shooting a stone into his single eye with a sling and became the High King.

This epic story speaks clearly of Nuada’s bravery in combat, the slicing off of his arm and its raising on a fold of stones, the crafting of his silver hand and the magical regeneration of his flesh-and-blood hand, his loss and regaining of his sovereignty, his special friendship with Lug, and his death.

We might expect to discover a parallel mythos in ‘The Fourth Branch’ of The Mabinogion, which tells the story of the House of Dôn, who are cognate with the Tuatha Dé Dannan. Lleu Llaw Gyfes ‘Skilful Hand’ is a central figure and his story shares similarities with his cognate, Lug**. However, Lludd is not mentioned at all. Math is the sovereign of the House of Dôn and the grandfather of Lleu.

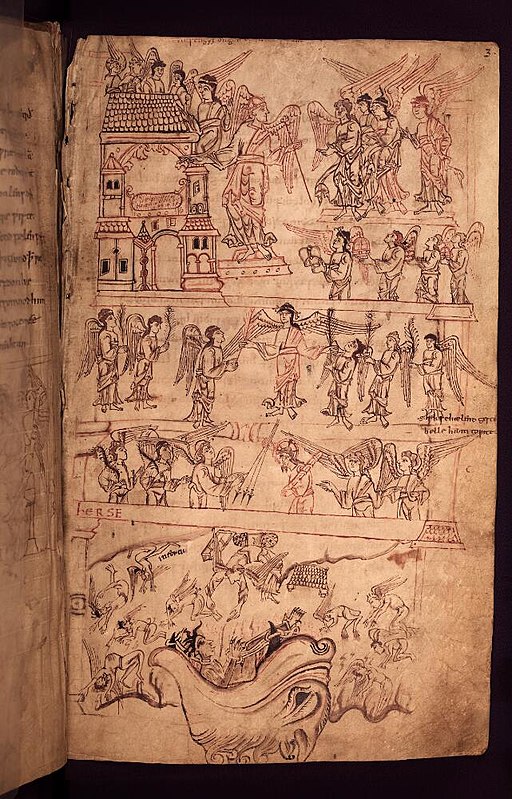

Will Parker suggests a parallel with the battle against the Formorians may be found in the ‘The Battle of the Trees’, from The Book of Taliesin, where the House of Dôn took on the forces of Annwn, the Otherworld. According to Triad 84 this ‘Futile Battle’ was initiated when Amaethon stole a lapwing, a dog, and roebuck from Arawn, King of Annwn. Gwydion enchanted the trees*** and Lleu was the battle-leader, ‘Radiant his name, strong his hand, / brilliantly did he direct a host’.

Amongst the enemy were ‘a great-scaled beast’, a ‘black-forked toad’, and ‘speckled crested snake’. Two englyns**** suggest Brân the Blessed, a gigantic son of Llyr previously associated with moving woodlands, now dead, fought amongst the people of Annwn. Once again, frustratingly, Lludd is conspicuous by his absence. If this was the battle where he lost his hand, his story has been lost.

Lludd appears instead in Lludd and Llefelys. He is introduced as Lludd Llaw Eraint, King of Britain. He already has his silver hand. The narrator presupposes the audience know the back story. We are told Lludd was a son of Beli Mawr, the father of Caswallon, who usurped the throne from Caradog, son of Brân, in ‘The Second Branch’. Assuming Lludd’s mother was Dôn this places him in a medial position between the Houses of Dôn and Beli. His power of mediating forms the heart of the tale.

We learn that, with advice from his brother, Llefelys, King of France, Lludd defeated three plagues, which bore some resemblance to the oppressions of Bres and the Formorians. The first was a people called the Coriniaid who were undefeatable because they could hear everything. The second was the scream of a dragon that blighted the land, causing loss of strength, miscarriages, barrenness, and crop failure. The third was a ‘powerful magician’ of ‘enormous stature’ who carried off Lludd’s provisions.

Lludd defeated them, not in epic battles, but through wit and magic. He banished the Coriniaid with a poison made from insects mixed in water. He calmed the two battling dragons by luring them into a well filled with mead, wrapped them in silk, and buried them in a stone chest. He caught the magician, who used a sleep spell, by standing in a tub of cold water to stay awake, defeated him in combat, then made him his vassal. Lludd then ruled Britain ‘in peace and prosperity’ until his death.

This story is set during the time of the Roman invasions. The Coriniaid (or Caesariad) were the army of Caesar who invaded in 55BCE and were driven from Britain by a wintry storm. Lludd’s dragon screamed because it was battling the dragon ‘of a foreign people’. Lludd’s calming of the dragons possibly represents him making peace between the Britons and Romans many years later. These historicised stories, particularly that of the battling dragons who fight again during the Anglo-Saxon invasion, are likely to have a deeper mythic basis. The magician was a purely otherworld figure.

Lludd mediated between threats from other lands and from the Otherworld and made peace with Llefelys’ aid. Their relationship bears similarities to the special friendship between Nuada and Lug.

In Britain Lludd’s role as a peacemaker rather than as a warrior was emphasised. The focus of his temple was not war but healing dreams. It’s my intuition his associations with healing may stem from his wounding, from the loss of his hand, his status as a wounded king. Silver-handed, he is whole-and-not-whole, and occupies a liminal and dreamlike position between Thisworld and the Otherworld.

It is of interest that Nodens/Nudd/Lludd’s son, Gwyn ap Nudd, is a ruler of Annwn. His role is to contain the fury of the spirits of Annwn to prevent their destruction of Thisworld. Gwyn is also a mediator.

Putting the evidence together we can conclude that Nodens lost his hand in a battle against some form of oppressor, possibly an Annuvian giant with a single eye, during ‘the mythic foretime’. His severed hand was raised on a fold of stone or paraded through the land with reverence and solemnity. Somebody, perhaps Gobbanus the smith-god, with the help of a physician, crafted him a silver arm. During this process he lost and regained his sovereignty. In the face of another threat Lugus arrived at his court and, in the ensuing battle, Nodens was killed and Lugus took his place.

Resurrected as King of Britain at the time of the Roman invasion Nodens/Nudd/Lludd worked with Lugus/Llefelys to bring peace to the island. Both deities were revered by the Roman Britons. After their veneration died their stories lived on and form an important part of the text we know as The Mabinogion.

And this was not Lludd’s only rebirth. In the name of King Lud, the eponymous leader of the Luddites, who struggled against the oppression of the Cotton Lords, we find echoes of Lludd’s name.

Again, as we are faced with oppression from right-wing groups and governments, he is invoked: “No King but Lludd!” As the sovereignty of the gods is affirmed against the corrupt rulers of Thisworld a fitting symbol of this time might be a silver hand; dealing blows, healing, bringing peace.

*Scholars have traced the story of the exile of the Israelites to prophets in 700BCE and suggest it may have happened around 1000BCE, although no archaeological evidence has bd een found to support.

** The attempts of Arianrhod, Lleu’s mother, to prevent him from winning a name, arms and a wife share parallels with Balor trying to stop Lug gaining a name and wife in order to prevent his prophesied death. Lleu’s defeat of his rival in love, Balor, with a spear-blow is similar to Lug killing Balor with a sling-shot or, in some cases, an enchanted spear.

***In The Battle of Moytura, Be Chuille and Dianaan, Lug’s ‘two witches’ said: “We will enchant the trees and the stones and the sods of the earth so that they will be a host under arms against them; and they will scatter in flight terrified and trembling.”

****These englyns are found in the Myvyrian Archaeology:

Sure-hoofed is my steed impelled by the spur;

The high sprigs of alder are on thy shield;

Bran art thou called, of the glittering branches.

Sure-hoofed is my steed in the day of battle:

The high sprigs of alder are on thy hand:

Bran by the branch thou bearest

Has Amathaon the good prevailed.

SOURCES

Edwin Hopper (transl), ‘The Battle of Moytura’, Edwin Hopper

John T. Koch (ed), The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, 2003)

Marged Haycock, Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin, (CMCS, 2007)

Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, (Faber & Faber, 1999)

Sioned Davies (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007)

Will Parker, The Four Branches of the Mabinogi, (Bardic Press, 2005)

‘Cad Godau’, Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective