Over the past few years the Heart of Annwn has become increasingly important in the mythos Gwyn has gifted me and in my devotional practices.

For me, the Heart of Annwn is Gwyn’s heart, inherited from His mother, Anrhuna, Mother of Annwn, and also the ever-beating heart of Annwn itself.

I believe that, like Hades and Hades, Hel and Hel, are both Deities and Otherworlds, Gwyn, who is associated with Gwynfyd is one with His land as well.

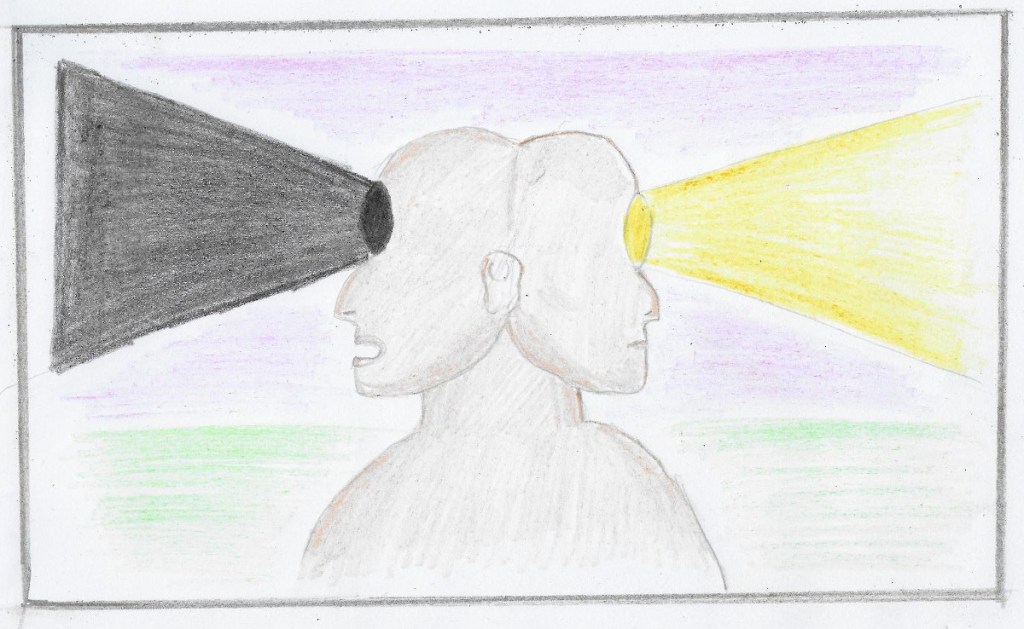

The Heart of Annwn literally became the heart of my practice two years ago when I began playing its beat and chanting to align myself with Gwyn’s heartbeat. This led to the formulation of the Rule of the Heart within the Monastery of Annwn – following our hearts in alignment with the Heart of Annwn.

In this post I will be sharing two of the core stories of the Heart of Annwn.

*

The Heart of the Dragon Mother

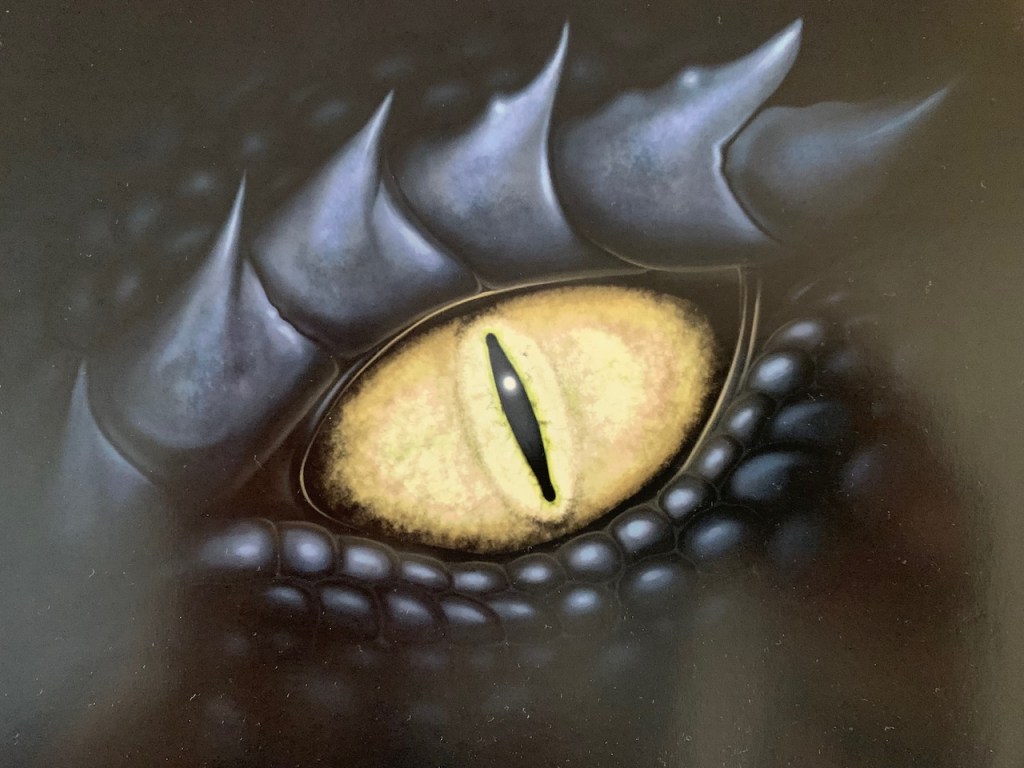

Gwyn has shown me that the Heart of Annwn once beat in the chest of His mother, Anrhuna, the Mother of Annwn, when She was a nine-headed dragon. When She was slain Vindos / Gwyn ate Her heart. The Heart of Annwn became His and this gave Him sovereignty over Annwn as King.

“Now,” the ghost of Anrhuna turned to her corpse, “there is a rite amongst the dragons of Annwn – as you are the only one of my children left here you must eat my heart.”

The boy swallowed nervously as with a single bite of her ghost jaws she tore it from her chest and offered it to him, big and bloody, large and slippery, uncannily still beating. “My heart is the Heart of Annwn. If you succeed in eating it all, its power will be yours and you will be king.”

“But it is so much bigger than I and I have little appetite.”

“Little bite by little bite and you will be king.”

The boy very much wanted to be king. He needed his kingship within him. He bared his teeth and bit in, took one bite, then another. As he ate, he grew. He became a mighty wolf, a raging bull, a bull-horned man, a horned serpent, finally, a black dragon. As he tore and devoured the last pieces of the heart he spread his wings to fill the darkest reaches of the Deep. He roared, “I am King of Annwn! I will rule the dead! I will build my kingdom from the bones of dead dragons and the light of dead stars! I will bring joy to every serpent who has known sorrow and I will take vengeance on my enemies!”

Weary and full he slept and when he awoke he was just a boy with a large heart that felt too big for his body.

*

The Hidden Heart

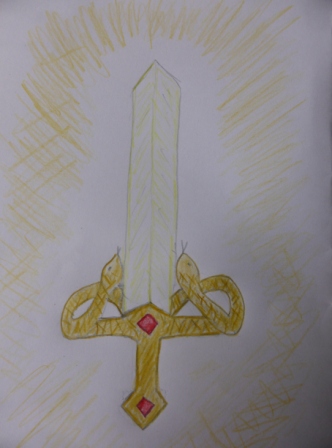

In another story, in which Arthur raids Annwn, killing the King of Annwn and stealing His cauldron, Gwyn instructs His beloved, Creiddylad, to cut His heart from His chest and help hide it so that Arthur cannot take the Heart of Annwn.

Gwyn gave Creiddylad a Knife. “Cut my heart from my chest. Give it to my winged messengers and tell them to hide it in a place that even I could never find It.”

“Do what?”

“I will not die.”

“Worse – you will be heartless.”

One of my practices around this story was receiving the honour of finding Gwyn’s heart and returning it to Him and helping Him to return to life.

‘I knew it was a death unlike any other

but still I heard the beating

of your heart…

Your hounds dug wildly beneath trees,

bloodying their frantic paws

to find only the hearts of

dead badgers,

sniffed suspiciously at the edge of pools

where I searched through reeds

as if looking for a baby

in the bulrushes,

plunged in

and emerged draped in duck-weed.

We snatched a still-beating heart

from a bear’s claws (not yours).

We searched every cave for a heart-shaped box.

When we found one

and the keys to the lock

inside was only a locket and a love letter in an illegible hand.

When we had searched everywhere in Annwn

we rode across Thisworld following

your fading heart beat.

We found your heart in the unlikeliest of places.

Clutching it tightly, fearing every time it skipped a beat,

we galloped back to Annwn with our hearts

beating just as wildly.

Through the fortresses within fortresses…

Into your empty chest we placed your still-beating heart.’

*

Gwyn has revealed a lot about the Heart of Annwn and I believe there is more to come. Recently I had a vision of Gwyn as a black dragon with His heart visible in His chest bearing an important message. He appears in this form when He brings tidings for the future. What will be the future of the Heart of Annwn? What stories from the past remain to be disclosed? I share what I know with gratitude and await further revealings.