An antlered skull

over

a

slither

of eternity

two bare feet

the

grooving

splintering

of bone

plucked

from your crown

and worked

into

a point

of beauty

and

barbarity

killed

and killer

as one

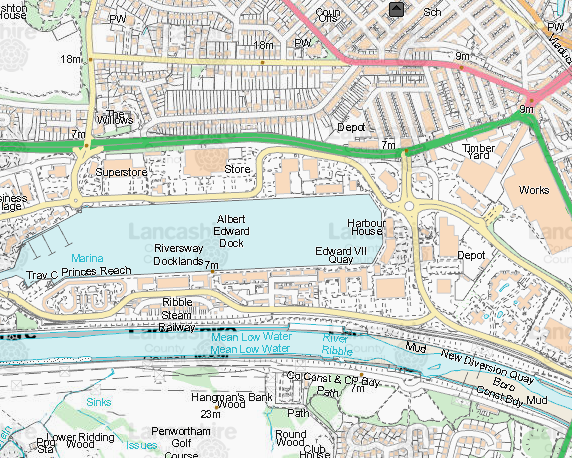

In 11,500BC Horace the Elk was killed by a combination of flint-tipped instruments and a barbed point that had lodged in his rib cage. Another barbed point was found embedded in the metatarsal bone in his left foot. The lesion formed around it suggests it had been there for around two weeks.

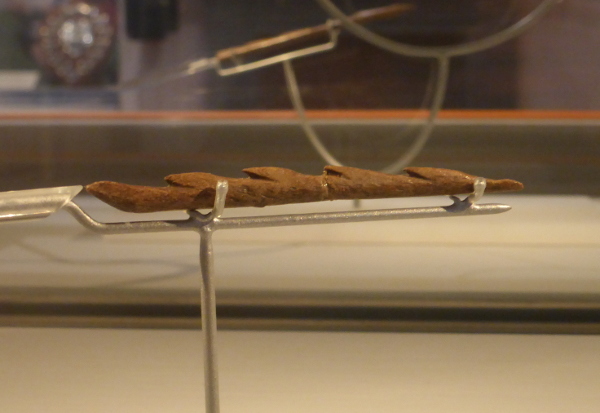

The barbed points used to kill Horace the Elk are the oldest known in Britain. Because they have only one barbed edge they are known as uniserial rather than biserial. Uniserial barbed points have been found across present-day England and Scotland and have been dated to between 11,500 and 8000BC.

All the barbed points were made specifically from red deer antler with a few examples from elk. I have been unable, as yet, to find out what material was used to killed Horace, but as elk and reindeer were the predominant species rather than red deer in 11,500BC, I suspect it was elk antler.

What intrigues me is the use of antler rather than other bones. This suggests antlers were chosen by the logic of sympathetic magic. As the primary ‘weapon’ of the elk and deer stags they were likely to have been seen as imbued with fierceness and strength and perhaps with the spirit of the dead animal.

Barbed points were made by the ‘groove and splinter’ technique. This involved cutting grooves lengthwise along the antler then splintering out long strips of bone. Afterwards, though processes of cutting, scraping, and filing, the barbs, tip, and haft were shaped before the point was fastened to its shaft.

For an animistic people this was no doubt a sacred process in which the maker of the barbed point engaged with the spirit of the dead animal and perhaps called for aid from the ancestors and hunter gods. A hunter deity may have been seen as a tutelary figure, perhaps part-human, part-animal, who passed on the knowledge of hunting to his or her people. The finished product would have been viewed as alive, inspirited, having its own personhood.

Barbed points have been referred to as ‘the dominant symbol’ of the Mesolithic like the stone axes of the Neolithic. At Star Carr, in the Vale of Pickering, in north Yorkshire, 191 barbed points were deposited in Lake Flixton along with 102 red deer antlers and 21 antler frontlets that may have been used in hunting rites. The points may have been made from the antler removed from the frontlets. Their return to their place of manufacture seems significant as does their ‘making whole’ by their deposition.

Star Carr was occupied from 9335 – 8440BC. It was a place where the identities of human and deer were intertwined. Where dead deer were brought to be eaten, barbed points for hunting deer were created from their antlers, and to which the points were returned. The start and end point of a cycle based around the lives and deaths of humans and deer.

The shift from the Mesolithic barbed point to the Neolithic axe as the primary deposition symbolises the change from the focus on hunting to shaping the land and from the use of bone to stone. Stone was no doubt easier to get hold of and perhaps stronger, but not linked to an animal. The sacred connection between killer and killed was severed and, with the later discoveries of bronze and iron, would not be revived again. An early step on the way to our loss of an animistic worldview and our relationship with the animals we kill and eat and with the hunter gods.

*My main source for this post was Benjamin Joseph Elliott’s massively informative PhD thesis ‘Antlerworking Practices in Mesolithic Britain’ (University of York, 2012).