‘the severed head represents a discrete category of bog deposit, which appears to be particularly well represented in Lancashire’

David Barrowclough

Until recently it was believed that the 23 human skulls found on Penwortham Marsh during the excavations for Riversway Docklands provided evidence for human sacrifice or a mass murder. This was based on the premise that they were all contemporary with the Bronze Age spearhead, the remants of a wooden lake dwelling, and two dug-out canoes, which they were found with.

Since then a sample of the skulls have been radio-carbon dated to between 4000BC and 800AD. Four are from the Neolithic period, one the Romano-British, and one the Anglo-Saxon. The range shows these people died at very different times. This has led professor Mick Wysocki to put forward the theory that the skulls belonged to people who died upriver, their corpses floating down to a tidal pool at Penwortham Marsh where their heavy skulls sank whilst their bodies washed out to sea. Wysocki’s theory is widely accepted among historians and archaeologists.

I believe that, for many cases, Wysocki might be right. However, considering the surrounding evidence, I don’t think we can rule out the possibility that some of the skulls were purposefully deposited in Penwortham Marsh. Lancashire (the historic county) has many examples of ritual depositions of severed heads.

On Pilling Moss was discovered ‘the head of a woman with long plaited auburn hair… wrapped in a piece of coarse woollen cloth and with it were two strings of cylindrical jet beads, with one string having a large amber bead at its centre.’ The jet beads date it to the Early Bronze Age. Another female head with plaited hair, from Red Moss, Bolton, remains undated.

From Briarfield, on the Fylde coast, we have the head of a man aged less than 50 years ‘deposited in a defleshed state without the mandible’ and dated to the Late Bronze Age. Another male skull, of a similar age and date, was found on Ashton Moss, Tameside. A skull from Worsley was dated to between the Bronze Age and Romano-British periods. Found near the famous Lindow Man, the head of Lindow Woman has been dated to 250AD. Heads, as yet undated, were also found at Birkdale, near Southport.

The purposeful deposition of the heads, without their bodies, suggests they were deposited for ritual purposes. The plaited hair of the females seems significant. The jet and amber beads with the woman on Pilling Moss implicates she was an important figure among her people. These burials appear to have been made with great reverence. I wonder whether they are suggestive of the belief that the head is the seat of the soul and if it is treated in a certain way the soul might remain present so that a group of people can commune with the deceased until the time of its burial.

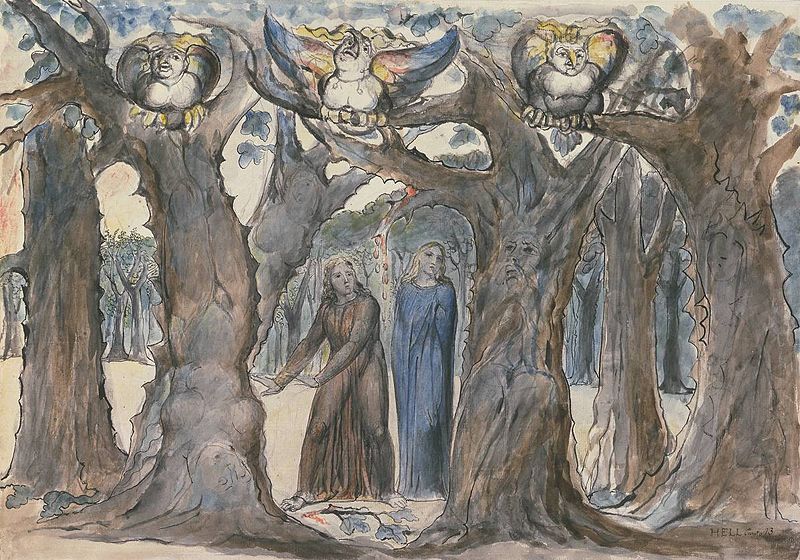

The existence of this belief within Brythonic culture is supported by ‘The Second Branch’ of the medieval Welsh text, The Mabinogion, in which Brân the Blessed’s head continued to speak for eighty years before its burial beneath White Hill in London to protect the Island of Britain from attack (until it was dug up by King Arthur who couldn’t stand anyone defending the country but him). It seems possible these heads also had a apotropaic function, demarking territory, repelling enemies.

Whilst the two female heads appear to have been buried reverently, the head of the man from Briarfield was badly mutilated – defleshed and and the mandible removed. David Barrowclough suggests the ‘separation of the mandible’ might show it was a ‘battle trophy’. That the removal of the flesh and the mandible might have been representative of one group or person over this person. One can imagine this gory spectacle as a symbol of glory over a defeated foe and a warning to an enemy.

Again this tradition is hinted at in medieval Welsh mythology. In Culhhwch and Olwen, prior to his beheading and the placement of his head on a stake the giant, Ysbaddaden Bencawr, had his ears cut off and his flesh was pared down to the bone. In Geraint there is an enchanted game where heads on stakes stand in a hedge of mist and it is implied that any who lose the game end up losing their heads.

In The Red Book of Hergest exists a poem attributed to Llywarch Hen in which the sixth century northern British ruler carries his cousin Urien’s head back to the kingdom of Rheged after his assassination:

A head I bear by my side,

The head of Urien, the mild leader of his army–

And on his white bosom the sable raven is perched…

A head I bear from the Riw,

With his lips foaming with blood–

Woe to Rheged from this day!

It has been suggested that Llywarch Hen ruled Ribchester in Lancashire (amongst many other places!)

Ritualised beheadings, burials (and unburials) of heads continued in Britain until 1747 when the Jacobite leader and Scottish clan chief, Simon Fraser, was publically beheaded at Tower Hill.

I therefore believe it is possible that some of the heads from Penwortham Marsh were ritual depositions. It seems to be of no coincidence that, of the six examined, three died violent deaths. A Neolithic man was killed by a stone axe and a Neolithic woman by ‘trauma to the right and back of her skull’. A Romano-British person (the sex cannot be determined) met his or her death through ‘a pointed object such as a spear passing through the open mouth and into the skull.’

These people could have been killed and their corpses deposited in the Ribble upriver. Or they might be the heads of people in the group of lake dwellers who at one point built a wooden structure on Penwortham Marsh. Perhaps they were locals killed in battle or enemies whose heads they had taken.

A further possibility is that they were human sacrifices. The Lindow Man famously died a ‘three-fold death’. He was struck on the head (with a blow that fractured his skull), garrotted, then drowned. Lindow Man was buried whole, but only Lindow Woman’s head was buried. The reasons why, in one instance, a whole body was deposited and in another only the head remain unknown.

Perhaps examinations of the other 17 skulls from the Riversway Dock Finds would provide further clues?

Another tradition that has lived on here is the deposition of stone heads (perhaps modelled on an ancestor?) rather than the heads of the dead in the Ribble as evidenced by this specimen in the Harris Museum.

*With thanks to the Harris Museum for permission to use the photograph.

SOURCES

David Barrowclough, Prehistoric Lancashire, (The History Press, 2008)Sioned Davies (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007)William Skene (transl.), ‘Red Book of Hergest XII, Four Ancient Books of Wales, https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/fab/fab060.htm (accessed 12/01/2020)

Display in the Discover Preston gallery in the Harris Museum