Dyed he is with the

Colour of autumnal days,

O red dragonfly.

Hori Bakusui

It was an accident. Still, if I’d accidentally killed a human I’d have been jailed for murder. I’m often killing midges, greenflies, flies, as I cycle down the Guild Wheel along the Ribble to Brockholes Nature Reserve. Not on purpose of course – they just have a terrible habit of getting in my eyes, in my mouth, down my top. It’s said there were more flying insects before cyclists, cars, climate change…

I’m not sure why killing a dragonfly somehow seems worse than killing all those tiny things. I didn’t even see him. I was too busy thinking about the fantasy novel that I was planning to set in a marshland and how the flora and fauna of Brockholes, as a wetland nature reserve, might inspire me.

Thinking not listening. There was just a buzzing at my neck and a kind of crackling against my skin. Without thinking I swatted at it compulsively, then stopped in a panic, fearful of what I’d done. Looking down, for a moment I felt relief, seeing what looked like a twig before I realised it was a ruddy abdomen. Severed from it a furred red-brown thorax, two cobwebby filmy wings, and a head with two huge dark red globular eyes and three small eyes that, between them, didn’t see me coming.

I didn’t know what he was right then, that he was a he, or a common darter. Only that I’d killed a dragonfly. I laid the broken pieces at the side of the cycle way with an apology to dragonfly kind and rode onward more slowly, more aware of other ruddy darters rising from where they were basking on the path. After I’d arrived, locked up my bike, they haunted me for the short period I was there. Flying in front of me, landing on the wooden walkways and handrails.

One, in particular, caught my eye. Beholden by the huge round portals of his eyes I drowned in the utter inadequacy of not knowing what he was thinking. Did he know I was a murderer? Did he know what I was? Could he sense my awkward reaching? My overall impression was one of curiosity. That it seemed likely he was thinking dragonfly thoughts distant from my own – trying to place this gigantic monster with its small eyes within his brief sunlit world of eating and flying and mating.

Dragonflies are old. The oldest fossils date back to the Carboniferous period – 350 million years ago. They spend most of their lives as nymphs, living for up to four years in muddy waters. They then crawl up the stem of a plant and shed their nymph-skin, emerging as dragonflies, leaving behind the exuvia. In the brief six months of their adult life they feed on smaller flying insects and find a mate, in an acrobatic display forming a spectacular mating wheel, then afterwards the female lays her eggs on the leaves of plants or in the water. Death follows shortly and the life cycle begins again.

It’s impossible to know if that dragonfly had fulfilled his life’s purpose before I killed him. And, of course, in that all-too-human way that has reduced the earth and its creatures to resources, I’m searching for a meaning, like nature is here to teach us lessons. I can’t help it. That’s human nature.

And it’s pretty obvious, slow down, listen, maybe just maybe I’m heading off on the wrong path trying to write a fantasy novel about an imaginary marshland when our existing wetlands need our voices. Making up new creatures when it may be more valuable to introduce people to Sympetrum striolatum ‘common darter’, Sympetrum sanguineum ‘ruddy darter’, Anax imperator ‘emperor dragonfly’.

This is leading me to think that, rather than writing second world fantasy, I might be best off writing a novelset in this landscape, but further back in time. Not only before the wetlands, the marshes, the peat bogs, the lakes, were drained off, but before the people lost their spiritual relationship with the land.

I’ve long been drawn to the archaeological evidence for the ancient marsh-dwellers in my local area. During the Romano-British period they were known as the Setantii ‘The Dwellers in the Water Country’ but had lived here far longer. Here, on Penwortham Marsh (now drained) and not far from the river Ribble (now moved) they had a Bronze Age Lake Village evidenced by the remains of a wooden platform, dug-out canoes, a bronze spearhead, 30 human skulls, and skulls of aurochs and deer. There were numerous other settlements such as those beside the great lakes Marton Mere and Martin Mere (now drained), wooden trackways such as Kate’s Pad, and the (now lost) Port of the Setantii.

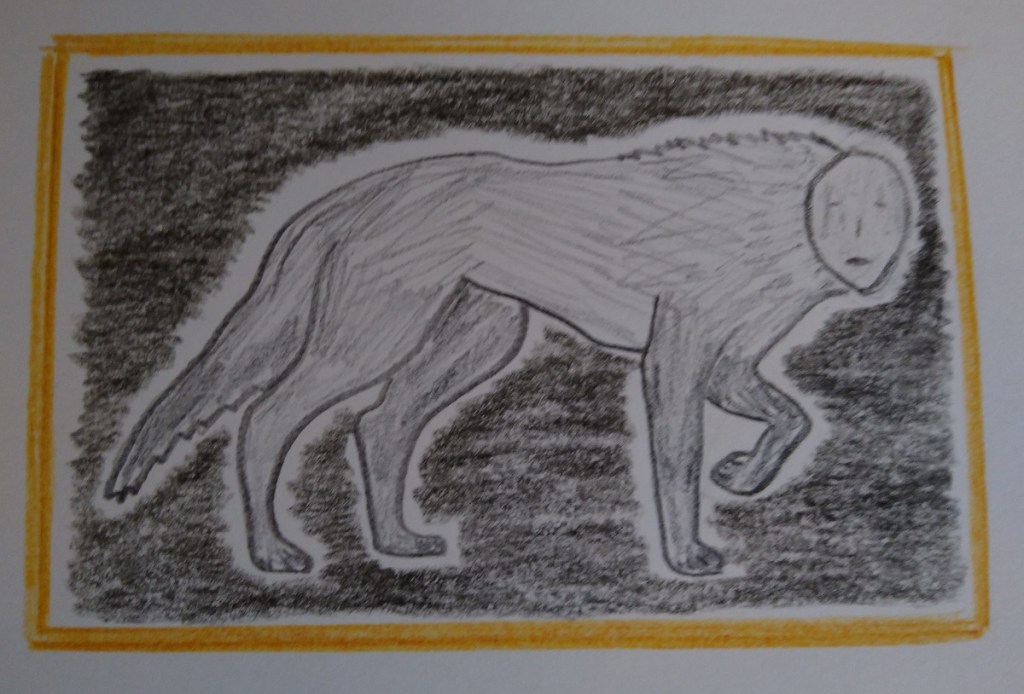

If I was to write about that time, rather than making up critters and magic and gods and monsters, I would be able to draw upon the real magic of an animistic and shamanistic culture rooted in a lived relationship with the ‘water country’ – its reeds and rushes, its wetland birds, its dragonflies and damselflies. With the spirits of the ancestors, gods we know throughthe Romans, such as Belisama and Nodens, and those who are unknown such as the goddess I know as Anrhuna, Mother of the Marsh.

That dragonfly was one of her children perhaps. She who has been here as the marshland since, at least, the thaw of the Ice Age and thousands of years of water country, these last four centuries of its draining off, and is still here in the last remnants preserved by wetland nature reserves such as Brockholes.

Would it be too very human to read, in an unlucky accident, a message from a goddess?

O red dragonfly,

Colour of autumnal days,

Dyed he is with the

Mother of the Marsh

Returned to mud and water

Rest well O red one.

***

Those who follow this blog will note this event has led me to returning to its old name ‘From Peneverdant’. This was the name of my hometown of Penwortham in the Doomsday Book and signals a homecoming from an exodus through Welsh mythology and Annwn. It makes sense in relation to my lifelong dedication to Gwyn, here, in January.