It has been the worst year

since I have been born.

I have felt hurt, anger,

resentment, abandonment,

wondered if I’ve made a mistake.

If my choice to dedicate myself to you

has brought family sicknesses,

plague, landslips, floods…

But, you reassure me, it has not –

you warned me of the sadness

coming to this land long ago.

In your thereness I have found

strength knowing how tirelessly

you guide the dead (so many!).

You have laughed away my fears.

When I’ve cried, wailed, wallowed

in self pity and uttered every expletive

in Thisworld and Annwn told you:

“I’m afraid I’m going crazy…”

you have shown me the lives and deaths

of your spirits – what true madness is –

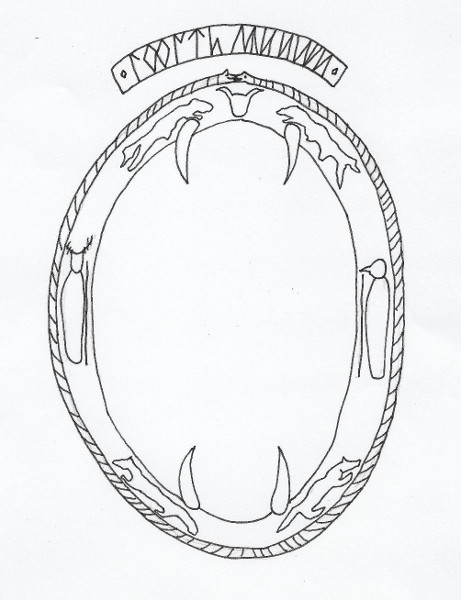

Annwn’s multi-sided perspective.

You have been there for me

through the worst year as you are

always there for the living and dead.

I have been blessed in my service to you

as your awenydd whether in words or in work

in the woodlands and the marshlands…

Tonight, in your cauldron, help me transform

my battle-fog into mists of enchantment.

White, Blessed, Holy, be not only

the Wrathful Hunter but the Kindly One.

Help me delight in being yours again.

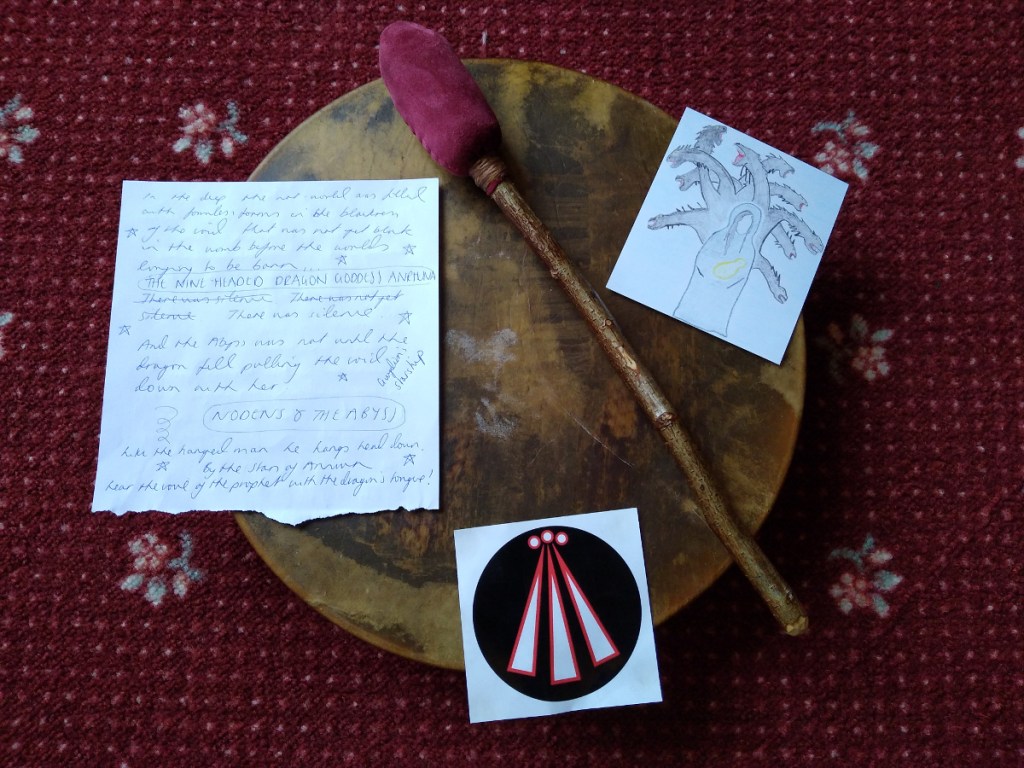

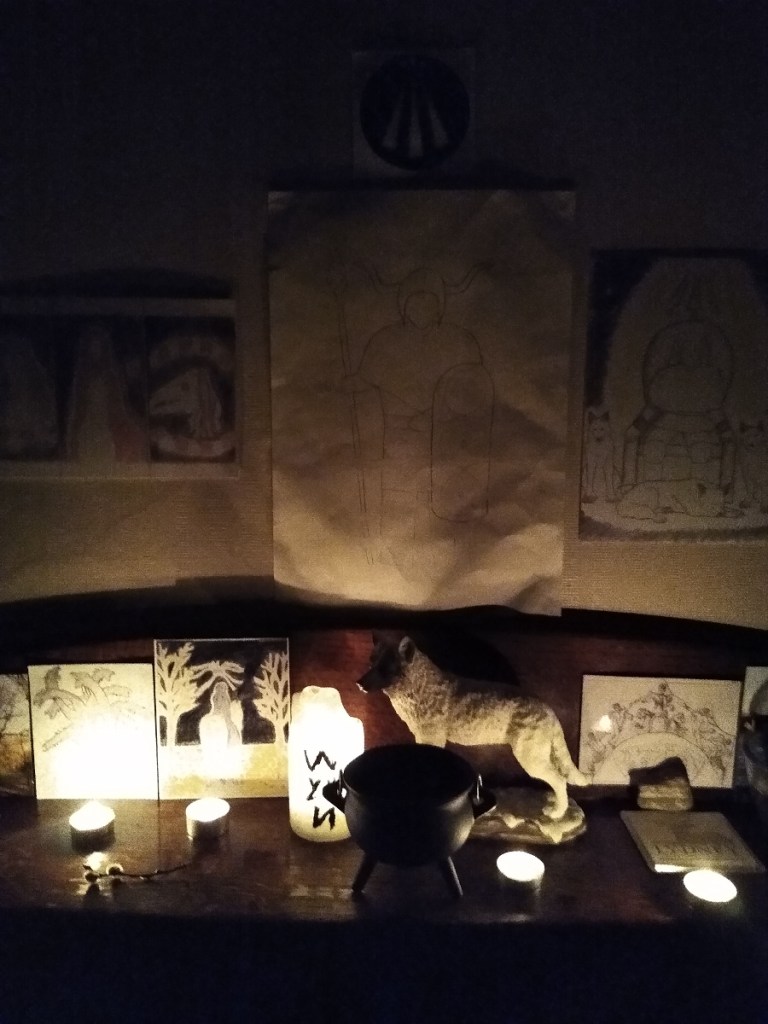

I wrote the poem above, addressed to Gwyn, to mark the two year anniversary of my lifelong dedication to him. This took place beside yew tree on Fairy Lane by the light of the ‘Super Wolf Blood Moon’. I had already served a seven year apprenticeship to him, most of which had been magical and wonderful.

The last two years have been far harder, in particular the last, for all the reasons stated above. Family illnesses, covid, minor natural disasters in my local area and far worse ones further afield.

All of these devastating signs of the consequences of climate change and overpopulation.

Last night, I performed a ritual to mark the anniversary of my dedication to Gwyn, which involved casting these happenings and the feelings of resentment and anger that were getting in the way of our relationship and my service to him as an awenydd into his cauldron to be transformed.

“Know that every thought, like all things, has a soul,” he reminded me, “like you dies and is reborn.”

During our communion Gwyn gave me a combination of warnings, reassurance, and guidance.

“There is harder to come. I will give you no false hope or empty promises. Yet I can provide inspiration. In the journey of the soul you are not alone. Both the living and the dead face these problems. I too, for we all connected. Set aside your resentment and reach out in cooperation. Every thought, word, act, has its effects running through both worlds and throughout time. Know these cannot be predicted but even the worst horrors can turn to awen in the cauldron.”

So the magic of Annwn was worked and this morning I awoke to the full moon shining over my garden.