Boar Hunt (from Moniack Sloe Liqueur)

I.

Recovering the Memories

Introduction: The Hunt for Twrch Trwyth and the Impossible Tasks

Within the main narrative of Culhwch and Olwen (1325) lies the story of the hunt for Twrch Trwyth ‘King of Boars’. To win Olwen, Culhwch must fulfil forty impossible tasks. These are set by Olwen’s father Ysbaddaden Bencawr ‘Hawthorn Giant’. The purpose of hunting the Twrch is to take the comb, shears and razor from between his ears so Ysbaddaden’s thorn-bush beard can be untangled, cut and shaved on the day of the wedding feast.

Twrch Trwyth is not just a huge silver, bristly, hoary, old boar but the son of a human chieftain: Taredd Wledig. He was reputedly turned into a boar by God as punishment for his sins. Beneath this Christian veneer lie deeper animistic roots disclosing Twrch Trwyth’s personhood and significance as one of Britain’s ancestral animals.

Irish and Norse myths feature magical boars who are hunted, killed, eaten, then the next day made whole. These could be rooted in tribal perceptions of father and mother animals who generate so long as they are treated respectfully. It is likely similar beliefs were found in Britain. It is of interest to note the Twrch is the father of seven piglets.

The list of impossible tasks contains the names of huntsmen, hounds and horses who are needed to hunt Twrch Trwyth. These include other mythic and numinous figures such as the pre-Christian hunter-deities Gwyn ap Nudd and Mabon mab Modron and a number of legendary hounds and huntsmen. Culhwch does not recruit these personages himself. He enlists the help of Arthur, who gathers and leads the hunt for Twrch Trwyth.

Gwyn’s Leadership of the Hunt

It is my intuition Arthur’s hunt for Twrch Trwyth is based on an older and more primal hunt led by Gwyn ap Nudd ‘White’ or ‘Blessed’ ‘son of Mist’. Gwyn appears as a divine warrior-huntsman with his white stallion, Carngrwn, and white red-nosed hound, Dormach in The Black Book of Carmarthen (1250). Here his role as a gatherer of souls is disclosed.

In later Welsh folklore Gwyn is associated with the Cwn Annwn ‘Hounds of the Otherworld’ and depicted hunting the souls of sinners. Many modern pagans view Gwyn as the Brythonic leader of the pan-European Wild Hunt. The longevity of Gwyn’s lore demonstrates his ongoing significance as a hunter-god and psychopomp within Britain’s consciousness.

Culhwch and Olwen is the only place Gwyn’s associations with the hunt for Twrch Trwyth can be found. However parallels exist within Irish and Norse mythology. Gwyn’s Irish counterpart, Finn ‘Fair’ ‘White’, leads the hunt for the giant destructive boar of Formael. The Norse hunter-warrior god and psychopomp, Odin, feasts on a mythic self-generating boar called Saehrimnir with his host of dead fighters in Valhalla.

Whereas Finn and Odin are central figures in Irish and Norse mythology, Gwyn plays a more marginal role in the British myths. I believe Gwyn may have once possessed a much greater mythos akin to the Fenian Cycle and the body of lore surrounding Odin.

Due to Gwyn’s rulership of Annwn, the Brythonic otherworld or underworld, he and his hunt have been demonised and marginalised through centuries of Christianity. Annwn has been identified with hell, Gwyn and his huntsmen with demons and the Cwn Annwn with hell-hounds.

This process can be traced within Culhwch and Olwen. Reading the narrative ‘otherwise’ to expose its sub-text shows how Gwyn’s mythos has been suppressed and replaced by Arthur’s. From its deeper levels memories of Gwyn’s hunt and the identities of its members can be recovered.

The Spirits of Annwn

Ysbaddaden tells Culhwch ‘Twrch Trwyth will not be hunted until Gwyn ap Nudd is found’. This may refer obtusely to Gwyn’s earlier leadership of the hunt which cannot begin without its divine leader.

Gwyn is impossible to get because ‘God has put the spirit of the demons of Annwn in him, lest the world be destroyed. He will not be spared from there.’ Ysbaddaden’s words hint at Gwyn’s rulership of Annwn and containment of its spirits.

Gwyn’s paradoxical nature as a white and blessed protector on the one hand and the ‘dark’ embodiment of the fury of the spirits of Annwn on the other is too much for the dualistic logic of Christianity to handle. Hence it calls for an explanation via the agency of God. This intolerable ambiguity is the source of Gwyn’s marginalisation and suppression of his myths.

The only clue I have found to the identity of the spirits of Annwn is an inscription from Chamalieres invoking the Andedion ‘Underworld Gods’ including ‘Maponos Arvenatis’. Maponos ‘The Son’ was the Gallo-Brythonic name of Mabon; a pre-Christian deity of youth and hunting who also appears in the impossible tasks. Mabon’s mother, Modron, is the daughter of Avallach, a King of Annwn. Mabon’s Annuvian nature is clear.

Thus it seems possible Mabon and other figures found imprisoned or underground in the narrative of Culhwch and Olwen are spirits of Annwn and members of Gwyn’s hunt. It seems significant some are viewed as prisoners of Gwyn and it is Arthur’s task to liberate them. By freeing huntsmen, hounds and horses from imprisonment in the underworld, Arthur removes them from Gwyn’s containment and finally usurps his role as the leader of the hunt.

II.

The Members of Gwyn’s Hunt

Who are the members of Gwyn’s hunt?

It is possible to locate them in the Impossible Tasks in Culhwch and Olwen.

Drudwyn and Graid son of Eri

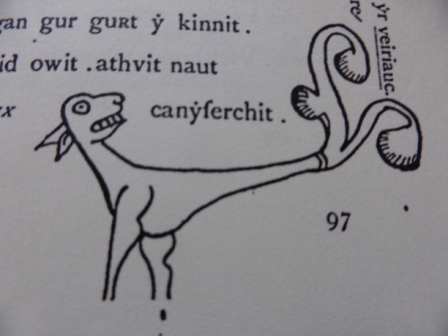

One of Culhwch’s impossible tasks is to get Drudwyn ‘Fierce White’ who is so fierce and strong no leash can hold him except the leash of Cors Cant Ewin. No collar can hold the leash but the collar of Canhastyr Can Llaw plus… the chain of Cilydd Canhastyr is required to hold the collar along with the leash!

Drudwyn has clear Annuvian qualities. I’m reminded of a later folkloric reference to an ‘Infernal Dog’ which takes the form of a mastiff with a white tail and white snip down its nose and grinning teeth which conjures a fire around it.

Drudwyn is the ‘whelp’ of Graid son of Eri. In the episode of Gwyn, Gwythyr and Creiddylad, Graid attacks Gwyn with Gwythyr’s army and is resultingly defeated and imprisoned by Gwyn then rescued by Arthur. It seems likely this takes place in Annwn.

This episode is flanked by the opening sentence ‘It is best to seek Drudwyn the whelp of Graid son of Eri’ and the closing words ‘Arthur obtained… the leash of Cors Cant Ewin.’ By rescuing Graid, Arthur also got Drudwyn and his leash. Thus Graid, Drudwyn and his leash may all be seen as brought from Annwn.

Mabon mab Modron

However it is not Graid who is destined to hold Drudwyn on the hunt but Mabon mab Modron. Mabon is an important god of youth and hunting in his own right. I have previously noted his associations with the spirits of Annwn and descent from Modron, daughter of Avallach: A King of Annwn.

In Culhwch and Olwen Mabon is impossible to get because he was stolen from Modron when he was three nights old. Nobody knows where he is or whether he is alive or dead. Arthur’s men find it necessary to consult the oldest animals: the blackbird of Cilgwri, the Stag of Rhedynfre, the Owl of Cwm Calwyd, the Eagle of Gwernabwy and the Salmon of Llyn Lliw.

This tale is of considerable antiquity and may date back to a pre-Arthurian variant where Modron herself was seen as wandering the earth conversing with the animals to find her lost son.

Arthur’s men are guided by the salmon to Caerlowy (Gloucester) where Mabon is found lamenting in a ‘house of stone’. He complains ‘no-one has been so painfully incarcerated in prison as I, neither the prison of Lludd Llaw Eraint nor the prison of Graid son of Eri.’

Arthur and his warriors arrive to defeat Caerlowy’s defenders whilst Cai tears down the wall and takes Mabon on his back. Mabon is borne ‘home’ and made a ‘free man’.

Links between Mabon, Graid and Drudwyn become clearer. They are all prisoners of Annwn released from its unhomeliness and redeemed of their Annuvian natures to join Arthur’s hunt.

Gwyn Myngddwn

Mabon’s designated steed, Gwyn Myngddwn ‘White Dark Mane’, was also got at the same time as Drudwyn’s leash. Gwyn Myngddwn does not belong to Mabon: he is the horse of Gweddw. Gweddw’s horse is listed as one of ‘Three Bestowed Horses of the Islands of Britain’ in The Triads as Myngrwn ‘Arched Mane’.

Gwyn Myngddwn’s white colouring and epithet ‘swift as a wave’ suggest he possesses Annuvian qualities and may be a water-horse. ‘Myngrwn’ is also suggestive of arching waves. Gwyn Myngddwn’s watery nature makes it possible for Mabon to ride him into the Hafren (the river Severn) and snatch the razor from between the Twrch’s ears.

Rhymi and Her Two Whelps

Another impossible task Arthur fulfils is capturing the ‘the two whelps of the bitch Rhymi’. Rhymi is fascinating because she is a shapeshifter who adopts the form of a ‘she-wolf’. It is enlivening to find a powerful female figure in this male-dominated narrative.

And more so when parallels with Irish mythology are considered. Finn owns two beloved hounds called Bran and Sceolang. They are the son and daughter of his aunt who was transformed into a dog whilst she was pregnant. Hence they are his nephews!

Gwyn’s descent from Nudd ‘the superior wolf lord’ suggests like his father he was theriomorphic and able to take canine form. Perhaps Rhymi and her whelps have familial connections with Gwyn.

Rhymi and her offspring dwell at Aber Cleddyf in a cave. The fact that they can live beneath a river underground is another sure indicator of their Annuvian nature.

When Arthur nears Aber Cleddyf he speaks with a farmer called Tringad who says Rhymi and her whelps have been destroying his landscape. Arthur boards Prydwen and leaves some men on the ground. Together they round up and capture the wolfish-hounds and God turns them back into their ‘own shape’.

I assume ‘own shape’ means human form. This contrasts with God fixing Twrch Trwyth in swine-form. Becoming animal is punishment whereas humanisation represents redemption. Rhymi’s whelps appear as hounds again on the hunt so this magic doesn’t last long.

Cynedyr and Cyledyr Wyllt

Rhymi’s whelps can only be held by a leash from the beard of Dillus Farfog. The only huntsman who can hold the leash is Cynedyr Wyllt who ‘is nine times wilder than the wildest beast on the mountain.’ Cynedyr is one of the gwyllon: madmen, wildmen or spectres who have intimate connections with the forest of Celyddon.

Celyddon is the Welsh name for the Caledonian Forest, which has long-standing associations with wildness and death. The 6th century Classical writer Procopius said north of the wall ‘it is actually impossible for a man to survive there even half an hour, but countless snakes and serpents and every other kind of wild creature occupy their area as their own. And, strangest of all, the inhabitants say that if a man crosses this wall and goes to the other side, he dies straight away… the souls of men who die are always conveyed to this place.’

In The Black Book of Carmarthen Myrddin Wyllt speaks of his flight to Celyddon after the Battle of Arfderydd to recover from trauma wandering amongst wild creatures and gwyllon. In The Life of St Kentigern (12th C) (as Lailoken) Myrddin shares his guilt and a vision of an unendurable brightness in the sky and host of warriors. One is described as a ‘demon’ who tore Myrddin out of himself and assigned him to the wild things of the woods.

It seems possible this company was Gwyn and the spirits of Annwn. Hence they played a role in Myrddin’s retreat to the forest and transition into wyllt-ness but also his recovery and acquisition of the powers of poetry and prophecy.

We know nothing more about Cynedyr Wyllt than his reputation for extreme wildness. Yet we find the story of Cyledyr Wyllt within the episode of Gwyn, Gwythyr and Creiddylad. Along with Graid son of Eri, his brother, Pen, his father, Nwython, Nwython’s uncle Gwrgwst Ledlwm and Gwrgwst’s father Dyfnarth, Cyledyr accompanied Gwythyr in his attack upon Gwyn.

During their imprisonment, Gwyn killed Nwython and fed his heart to Cyledyr, who went mad. I have no idea whether this gory scene is founded in ancient ancestral rites or superstitions about Gwyn or whether it was invented to demonise him.

It seems significant four generations of Strathclyde Britons are captured and Cyledyr is fed his father’s heart. Could Nwython’s heart be viewed as containing the life-force of his family? Could transgressing the moral bounds of Dark Age society be a form of initiation into Gwyn’s hunt? Consuming his father’s heart clearly makes Cyledyr ‘wyllt’.

Neither human or animal (Myrddin takes the form of a bird and Cynedyr is compared to a mountain beast), living or dead, the gwyllon occupy a liminal position similar to the spirits of Annwn.

Later, Arthur goes north and captures Cyledyr. Alongside Mabon, Cyledyr rides the Twrch into the Hafren and snatches the shears from between his ears.

III.

Gwyn’s Hunt and Impossibility

The Escape of Twrch Trwyth

Arthur’s hunt for Twrch Trwyth begins in Ireland. After the hounds are loosed, the Twrch lays waste to a fifth of the land. Arthur fights the boars for nine days and nights and only kills one piglet.

Twrch Trwyth and his piglets then swim across the sea to Wales. The Twrch kills men and beasts in Daugleddyf then cattle in Cynwas Cwryfagyl. At the river Nyder, he stands at bay. In the first round he kills four of Arthur’s champions. In the second he slaughters Arthur’s son, Gwydre, and several other men. The next day he kills numerous ‘men of the country’ including Arthur’s chief craftsman, three servants of his gatekeeper and the King of France.

Arthur’s men lose the Twrch at Glyn Ystun. At this point Arthur summons Gwyn to him and asks if he knows anything about Twrch Trwyth. Gwyn says he does not. It seems likely the Twrch has fled deep into the wild or taken shelter in Annwn and Gwyn is covering his flight from his adversary.

This makes it painstakingly obvious in spite of Ysbaddaden’s demand all the listed hunters are gathered before the hunt begins, Gwyn has not been got and is not riding with Arthur. There is no evidence of Gwyn’s recruitment in the text nor of the capture of his steed: the famous water-horse Du y Moroedd ‘The Black of the Seas’.

Following Gwyn’s evasion of revealing the location of Twrch Trwyth, Arthur’s men are forced to hunt his piglets instead. Of the group who take them on none survive except one. When Arthur arrives with men and hounds the Twrch returns to defend his little pigs. Four piglets are killed. Another piglet is slaughtered at Garth Grugyn. After the King of Brittany and Arthur’s uncles meet their end the last piglet is defeated at Ystrad Yw.

Arthur summons Devon and Cornwall and they agree to drive Twrch Trwyth into the Hafren. Arthur and his warriors fall upon the Twrch and souse him in the river. At this point Mabon and Cyledyr flank him and snatch the razor and shears. Two of Arthur’s servants drown.

Afterward Twrch Trwyth escapes to Cornwall. Following a confrontation which makes the preceding trouble look like ‘mere play’ the comb is taken. He is chased from Cornwall into the Cornish sea. It is noteworthy Arthur and his men do not (cannot, dare not?) kill Twrch Trwyth.

Perhaps the rite of killing the Twrch is preserved for Gwyn, his legendary water-horse, Du, and his Annuvian huntsmen alone. Only they possess the knowledge of Nudd / Nodens ‘the catcher’ which is required to hunt and kill this great magical silver-bristled ancestral boar and bear him away to the feast in the deep from which he runs wild again.

Impossibility and the End of the World

Although Arthur does not complete all the impossible tasks, the comb, shears and razor are wrested from between the Twrch’s ears. Ysbaddaden’s beard is untangled, cut and shaved (down to the bone and even his ears are cut off!) and after his decapitation Culhwch marries Olwen.

The Twrch is hunted and the shaving equipment won but at a terrible cost. A fifth of Ireland is decimated along with a good part of Wales. Countless huntsmen lie dead including members of Arthur’s court, his close companions and family, most notably a son.

One recalls Ysbaddaden’s caution: ‘Twrch Trwyth will not be hunted until Gwyn ap Nudd is found’. The reference to Gwyn’s containment of the spirits of Annwn, a task he cannot be spared from in case the world is destroyed, highlights the danger inherit in Arthur’s decision to usurp his role as leader of the hunt and contain it with the help of God. This raises the question of whether the consequences would have been so dire if they worked together.

I don’t believe this is possible. Gwyn’s paradoxical mythos which transgresses the bounds of civilised Christian society is not compatible with Arthur’s worldview. There is not room for two leaders of the hunt. Arthur’s usurpation of Gwyn’s role as a protector of Britain could be the key to his marginalisation.

The central fact about Gwyn’s hunt is it belongs to him and the spirits of Annwn: the not-world, the deep, the realm of impossibility where all boundaries between civilisation and wildness, human and animal, life and death break down.

Attempting to make the impossible possible Arthur contains Gwyn’s hunt in a form palatable to Christian civilisation for a limited amount of time before, like Twrch Trwyth, it slips back into the watery realm of impossibility.

It is my further intuition Gwyn’s hunt is not only bound up with the literal destruction of the world but the end of the worlds we create as people. It is associated with the dissolution of what is possible and the manifestation of the impossible and thereby with radical change at the deepest level.

Nicolas R. Mann writes: ‘Gwyn is not only a guide into Annwn but also mysteriously connected with the end of a world… Gwyn may be seen as a guide into the next human world.’

EPILOGUE

As centuries of disbelief dissolve

they can be seen again

on the misted edges of Celyddon.

Drudwyn’s fierce white face pushing forward.

Graid son of Eri with a tentative hand on his collar.

Bright radiant Mabon holding Drudwyn’s leash,

leading Gwyn Myngddwn arching

his white neck and tossing his dark mane.

Deep in the forest Rhymi shakes

velvety flaps of red ears

as she suckles a litter of soft white pups

who will one day run with young hunters.

Cynedyr and Cyledyr fly

on the wings of birds

traverse mountains

goat-footed.

Standing apart in ruffled white furs

with a steadying hand on Du’s neck

Gwyn listens with Dormach

to the song of the forest

for a sign it is time.

They call to us to take their hands

ride swift mounts steer bellowing hounds

through the gap in the skies

where nothing is impossible.

Should we choose to join them

it is wise to heed

Culhwch and Olwen:

know for better or worse

the fate of the world is at stake.