A while back I dreamt of watching a film in a cinema. The centrepiece was a dark tower on a looming hill. Turning on its foundations, raising and dropping its drawbridge, it possessed the power to command the shifting landscape, influence the weather, and draw people into its swallowing darkness.

At the end of the film the lights went off and a voiceover resonated through the cinema and every molecule of my being: “You are in the Dark Tower”. I believed the statement to be wholly true and was struck by a combination of fear and anticipation and the fulfilling of my destiny.

But the other people seemed completely unfazed. They continued munching popcorn, crackling crisp packets, slurping on straws, and laughing amongst themselves at the ‘special effects’. I felt incredibly angry they did not heed the otherworldly voice. The magic broke. I awoke.

***

I researched ‘the Dark Tower’ and learnt it appears in the folktale of ‘Childe Roland’. Reading this dismal story of a knight (‘childe’ means untested knight) assaulting the Dark Tower, which is identified with the castle of the King of Elfland/Fairyland, left me soul-weary. I’d heard its like so many times before….

The first record of ‘Childe Rowland’ is in Shakespeare’s King Lear (1606). Edgar, an exiled son in the guise of Tom O’Bedlam, recites its jumbled lines to a maddened Lear on the heath:

Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower came,

His word was still ‘Fie, foh, and fum,

I smell the blood of a British man.

The first whole version is recorded in Jamieson’s Illustrations of Northern Antiquities (1814). The sons of King Arthur; Rowland and his two elder brothers, are playing ball around a kirk. Their sister, Burd Ellen, runs after the ball, and disappears. Merlin tells them Ellen has been ‘carried away by fairies’ to ‘the castle of the King of Elfland.’

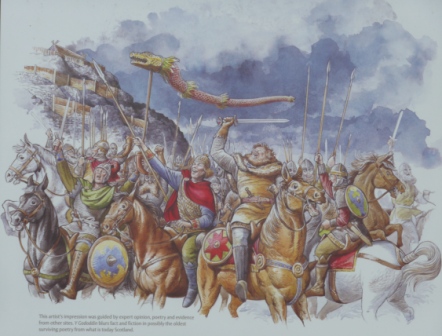

Rowland’s brothers fail to rescue Ellen because they do not follow Merlin’s instructions. Merlin tells Rowland to kill everyone he meets in the land of Fairy and not to eat or drink anything offered. Rowland asks directions to the king’s castle from a fairy horse-herd, cow-herd, sheep-herd, goat-herd, swine-herd, and hen-wife. After they aid him, he remorselessly beheads them.

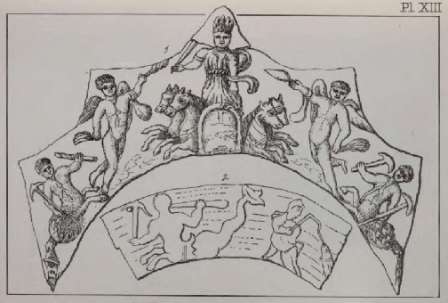

He arrives at ‘a round green hill surrounded with rings (terraces) from the bottom to the top’ and walks around it widdershins saying, “Open, door! open, door! and let me come in!” Through a twilight passage he enters a brilliant hall adorned with gold, silver, and clusters of diamonds, illumined by ‘an immense lamp of one hollowed pearl’ with a magically turning carbuncle.

Ellen sits on a sofa of ‘velvet, silk, and gold’. She warns Rowland that the King of Elfland poses a threat to his life yet, enspelled, offers him a golden bowl of bread and milk. When Rowland refuses to consume the fairy food the King of Elfland bursts through the doors yelling:

“With ‘fi, fi, fo, and fum!

I smell the blood of a Christian man!

Be he dead, be he living, wi’ my brand

I’ll clash his harns frae his harn-pan!”

“Strike, then, Bogle of Hell, if thou darest!” Rowland exclaims. He defeats the King of Elfland and offers to spare his life if he restores his brothers, who lie in trance in the corner of the hall, and Ellen. The King agrees. Producing a ‘small crystal phial’ he anoints the ‘lips, nostrils, eye-lids, ears, and finger-ends’ of the brothers with a ‘bright red liquor’. They awake ‘as from a profound sleep, during which their souls had quitted their bodies’ to speak visions.

In Joseph Jacob’s retelling in English Fairy Tales (1890) the brothers are not entranced but dead. Rowland demands the King ‘raise my brothers to life’ and ‘they sprang at once into life, and declared that their souls had been away, but had now returned.’ Fairyland is the land of the dead. Rolande’s quest, like Arthur’s before him, is to defeat the ruler of the dead and death itself.

***

This tale is repeated in Robert Browning’s poem ‘Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower Came’ (1895), which is based on a dream and written in the first person from Rowland’s perspective.

The guiding figure of Merlin is replaced by a ‘hoary cripple with malicious eye’ and ‘skull-like laugh’. The landscape is a ‘grey plain’ devoid of life aside from bruised dock and grass ‘scant as hair / In leprosy.’ Instead of herds, Rowland finds a single ‘stiff blind horse, his every bone a-stare.’

He is tormented by visions of other knights who set out to the Dark Tower and did not return: ‘Cuthbert’s reddening face / Beneath its garniture of curly gold’ and ‘Giles then, the soul of honour… faugh! what hangman hands / Pin to his breast a parchment?’

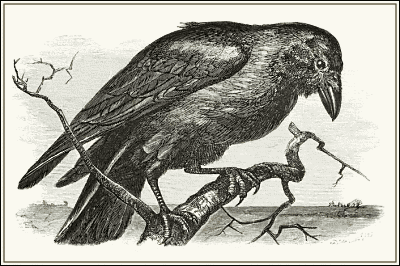

Fording a river lined with a ‘suicidal throng’ of ‘drench’d willows’ he is terrified of standing on a ‘dead man’s cheek’ or tangling his spear in ‘his hair or beard’. On the otherside he journeys across a trampled battlefield, through a furlong with an engine ‘fit to reel / Men’s bodies out like silk’, then over marsh, bog, clay, and rubble, to be led by a ‘great black bird’ with unbeating wings to his destination in the ‘mere ugly heights and heaps’ of the mountains.

‘The Tower itself’ is ‘the round squat turret, blind as the fool’s heart, / Built of brown stone, without a counterpart / In the whole world’. The ‘tempest’s mocking elf’ he aims to ‘stab and end’.

The poem ends with a vision of the dead:

There they stood, ranged along the hill-sides, met

To view the last of me, a living frame

For one more picture! in a sheet of flame

I saw them and I knew them all. And yet

Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set,

And blew “Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower came.”

It is is repeated again in Stephen King’s eight part dark fantasy series The Dark Tower (1982 – 2012) where Roland Deschain, a member of a knightly order of ‘gunslingers’ of ‘Arthur’s eld’ battles against ‘the Crimson King’.

***

This old tale of the sword-wielding, gun-toting ‘hero’ overcoming the fay and the dead and ultimately the King of the Otherworld has been repeating since Arthur defeated the Head of Annwn.

It’s so deeply ingrained in our consciousness we can’t imagine any other telling.

We sit munching popcorn confident the ‘hero’ will win and the ‘bad guy’ with his ‘fi, fi, fo and fum’ is all special effects.

What if that’s not the case? What if the knights in shining armour are rusting on the scrap heap of a false history, their journey is at an end, we are in the Dark Tower, and the King of Elfland is not just a one-dimensional comic book villain?

What new stories will unfold from the unknighted, the armourless, the weaponless?

Will we wait for the ‘hero’ to save us or is this where our story finally begins?

You are in the Dark Tower

The Dark Tower on the green terraces of Glastonbury Tor