In the middle of winter new shoots begin to show – snowdrop, crocus, daffodil, bluebell. I’m not sure if this has always been the case. But for the last six or so years one of my mid-winter rituals has been looking for new shoots.

New shoots have been showing in my life too. I’m starting to recover from the disappointment of In the Deep not being publishable and have come to terms with the fact the veto on my becoming a professional author is for good.

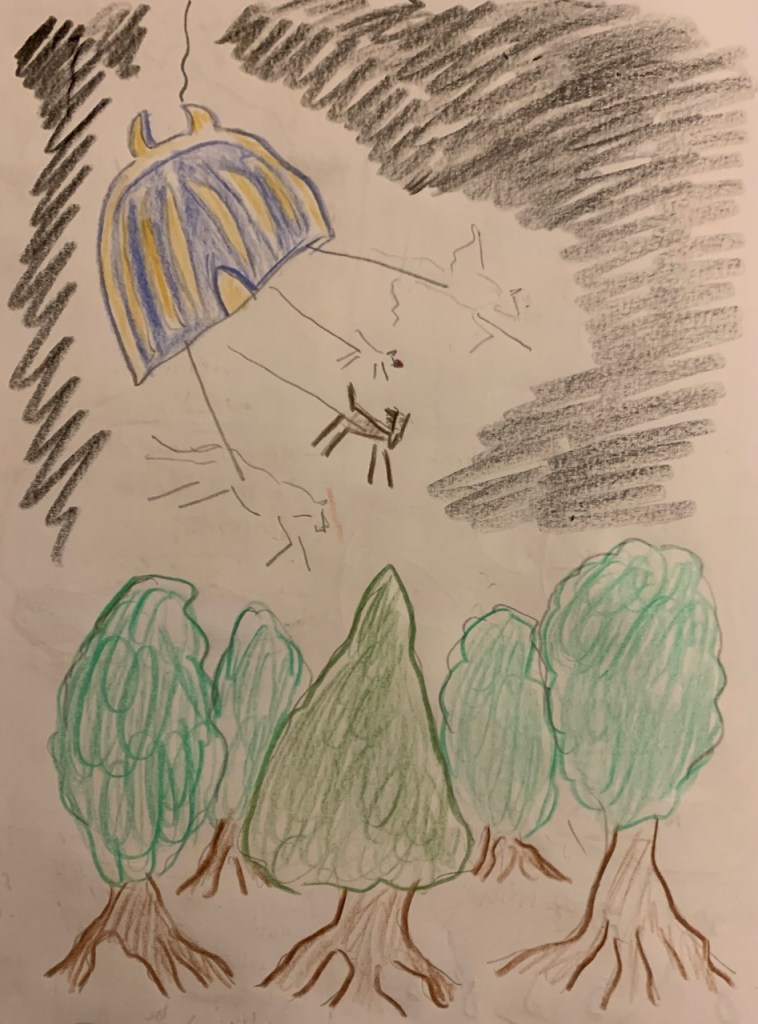

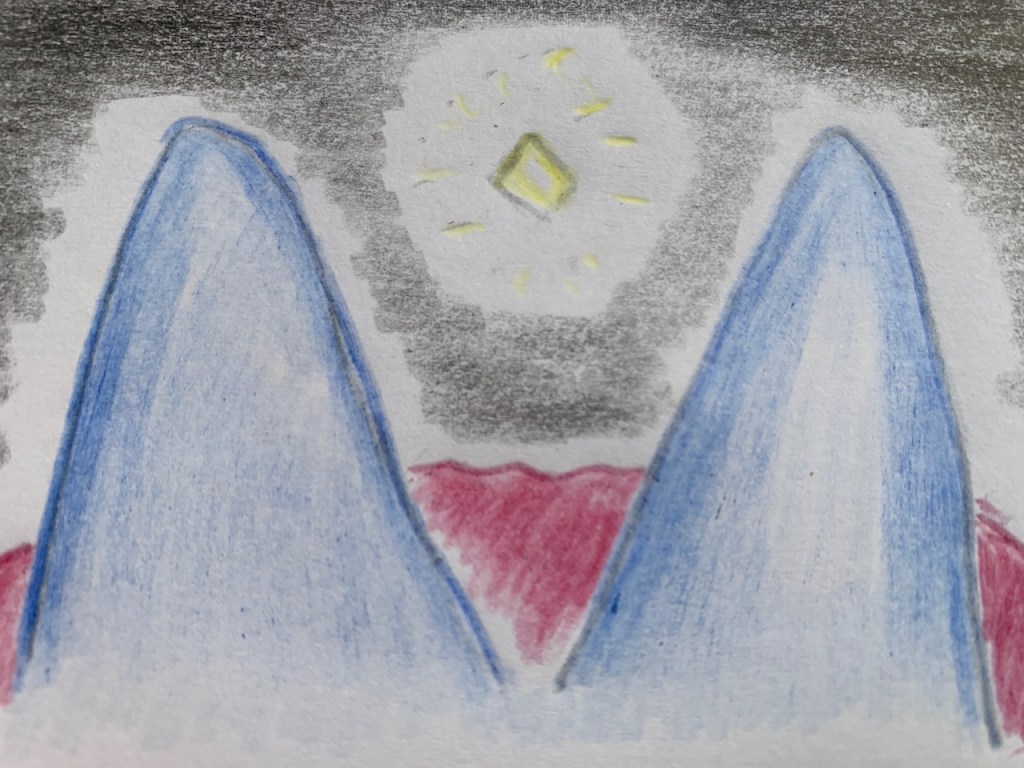

Before the winter solstice I attended a beautiful in-person workshop called Bear Moon Dreaming with my spiritual mentor, Jayne Johnson, in which she led a small group through shamanic journeying and dancing into connection with bear, the moon, and into the depths of the winter landscape and hibernation. In it I became one with the Water Country and Gwyn as Winter King giving gifts to the people.

Afterwards I realised I couldn’t live my life online anymore. Spending most of my day writing at my laptop and living through this blog has not been healthy.

Around the same time the forum for the Monastery of Annwn got deleted by the member who set it up without consent of the rest of the membership. I was shocked and angry but also a little relieved as I had been spending too much time online doing admin*. When I journeyed on what to do about it I found the monastery hanging by a thread in the Void and with my guides and other animals had to drag it back to the Forest of Annwn and reroot it. This became a metaphor for both what the monastery needs and I need too.

I spent the last moon cycle praying and discerning my future course. I received two answers and the first was that I needed to return to outdoor work. Previously I had been working in conservation and done a little horticulture and since then had been continuing to grow plants.

I have slowly been developing a relationship with Creiddylad as a Goddess of flowers with whom I have been working to improve our garden and the wildflower area in Greencroft Valley where I have volunteered since 2012.

So I have started volunteering with Let’s Grow Preston and Guardians of Nature with the hope this will lead to paid work. I feel horticulture will sit well with my vocation as monastics traditionally labour several hours in their gardens.

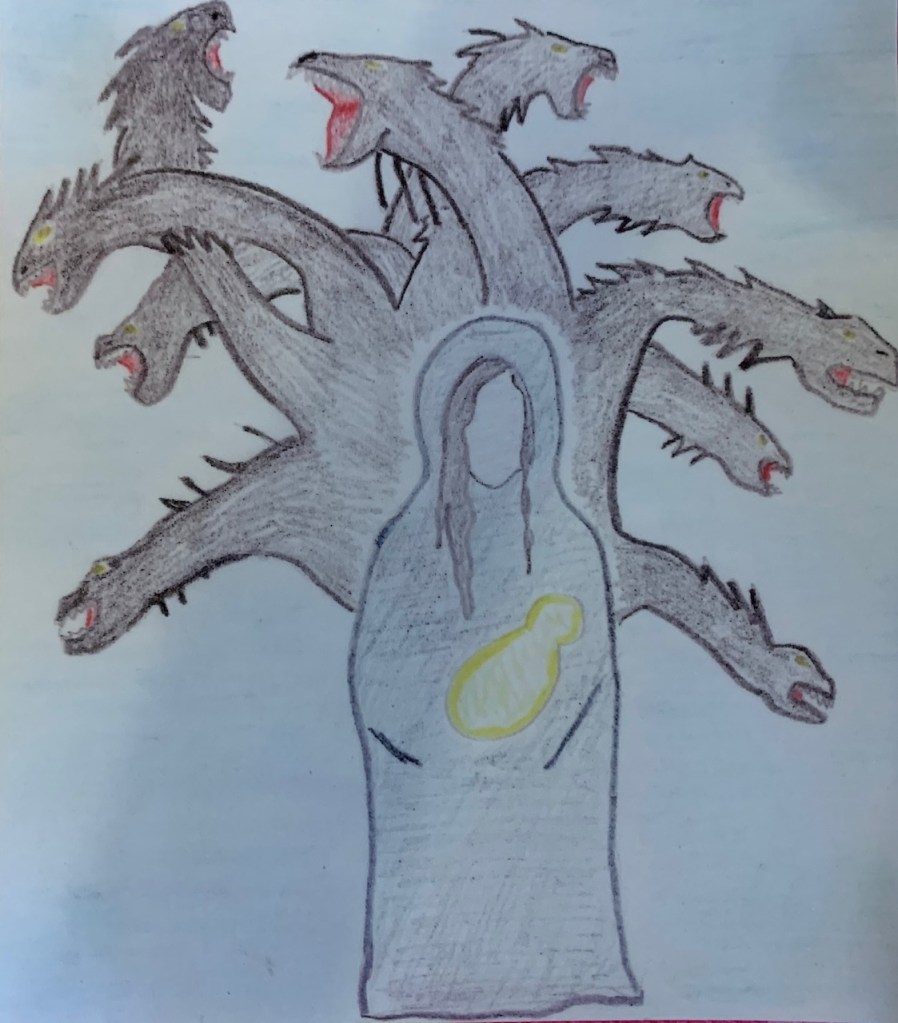

My second answer was to train to become a shamanic practitioner. This fit with my having been journeying with Gwyn for over ten years to bring back inspiration from Annwn to my communities and with my practicing core shamanism with the Way of the Buzzard and more recently with Jayne.

It’s something I’ve considered in the past but have been put off because I don’t feel good enough and have doubted whether I have it in me to be a healer.

Yet Gwyn has made it clear I must take this step and has assuaged my doubts. In relation to my presupposition, ‘I don’t have a healing bone in my body’, He reminded me of the time I had a similar thought, ‘I can’t grow things because everything I touch dies’, yet then got good at growing plants. He told me healing is a skill that lies within me and it is time to manifest it.

He also explained ‘it is like the transition between bard and vates’. I’ve been ‘the bard in the meadhall’. Giving up drinking has been for the purpose of clearing my head so I can hear the voices of the subtler spirits. Only I won’t later be becoming a druid but a nun of Annwn – an entirely new vocation.

Thus the new shoots push up through the surface and I see how to reroot. By getting my hands back in the soil through horticulture and working towards becoming a shamanic practitioner to heal both myself and others.

I will also be continuing to blog here about my journey and sharing devotional material as service to my Gods and for my patrons and wider readership.

*It turned out this wasn’t a bad thing as it has given us the chance to start looking for a better forum and share the administrative workload more fairly.